Peacekeeping, African warlords and Donald Trump

- Published

Fergal Keane visits Bambari - where UN peacekeepers separate two rival warlords.

A change of attitude towards peacekeeping under US President Donald Trump could spell disaster for places like the Central African Republic, where the presence of a UN mission is trying to keep notorious warlords in check, writes the BBC's Fergal Keane.

They are the masters of the fearful day. I have met them in the Balkans and Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

Their habitat is the failed or failing state where the most cunning and violent carve out fiefdoms.

There, they remain free to terrorise and extort from defenceless civilians.

They thrive best in places about which the world cares little, or at least does not care enough for the most powerful nations to send their troops to enforce a long-term peace.

Welcome to the world of the warlords. We may be seeing a lot more of them if President Trump keeps his promise to scale back American support for UN peacekeeping.

Some in the Trump administration have an aggressive dislike of the UN

Currently the US supplies 28.57% of the total budget for UN deployments.

There are very influential figures in the Trump administration with a visceral ideological dislike of the UN.

At the very least, the new UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, faces an uphill fight to persuade the US to keep paying its current share of the peacekeeping budget.

It was a debate much on my mind travelling in the Central African Republic (CAR).

Red lines drawn

At the moment, the UN's deeply-flawed mission (Minusca) is the only thing standing between that country and genocidal anarchy.

In fighting last weekend, UN attack helicopters engaged militia who were attempting to advance on the town of Bambari.

This very dilapidated, dusty town on the banks of the Ouaku River has become the first big test for UN peacekeeping in the age of Gutteres.

In an arc to the north, several militias are threatening to advance on Bambari.

The UN has drawn red lines, pledging to fight if the militias advance.

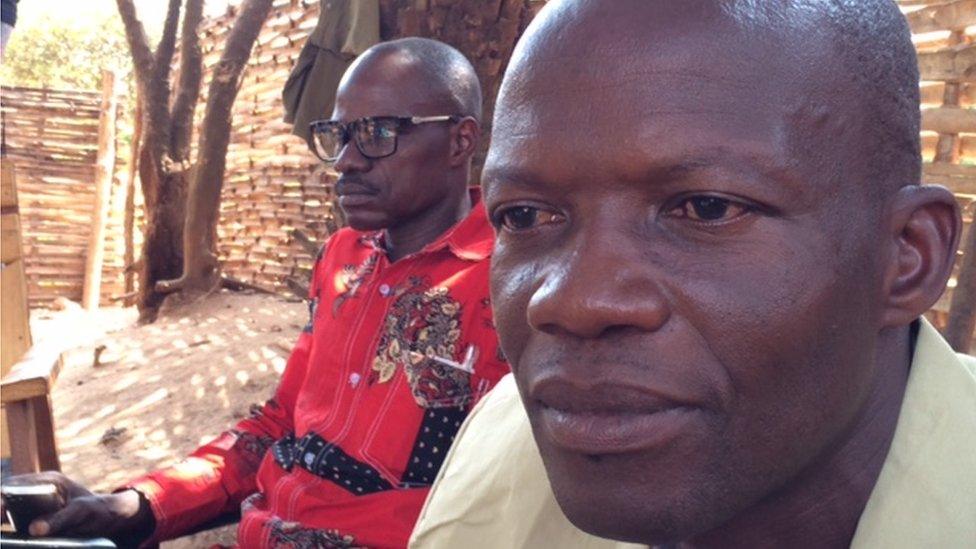

"General" Gaetan Boade (R), sitting by his aide-de-camp Tarzan, says he has 28,000 men

There are thousands of frightened displaced people in and around Bambari who are depending on the international community to keep its word.

But matters are complicated by the presence in Bambari of warlords like Gaetan Boade, known as "General Boade" a leader of the Christian "anti-Balaka" militia.

Gen Boade has never had much faith in the blue helmets of the UN. Nor does his more genial aide de camp, "General" Tarzan, a nickname given to him by his troops.

Their stronghold is on the Christian side of Bambari, across the Ouaku River among the narrow lanes of mud houses, a place whose poverty is indistinguishable from the dismal circumstances of their Muslim enemies.

Gen Boade wears a crumpled, mustard-coloured cotton suit and brown, buckled shoes.

He looks more like an out-of-work musician than a feared militia leader.

But he is admirably frank when I ask if he is a warlord: "Yes. I have 28,000 men who are ready to protect the people."

This is a substantial exaggeration but his men are regarded as a danger to the peace should they decide to fight.

The young toughs who make up his militia hid their guns during our visit.

But they are well armed and their leader is openly dismissive of the UN's ability to protect Christians.

"If the Minusca were able to protect us they would stop the guy who commits exactions, who takes people as hostages, who kills in front of their eyes. Has Minusca really come to protect us?"

No fear of blue helmets

Bambari is filled with weapons despite the UN declaring it a non-militarised town.

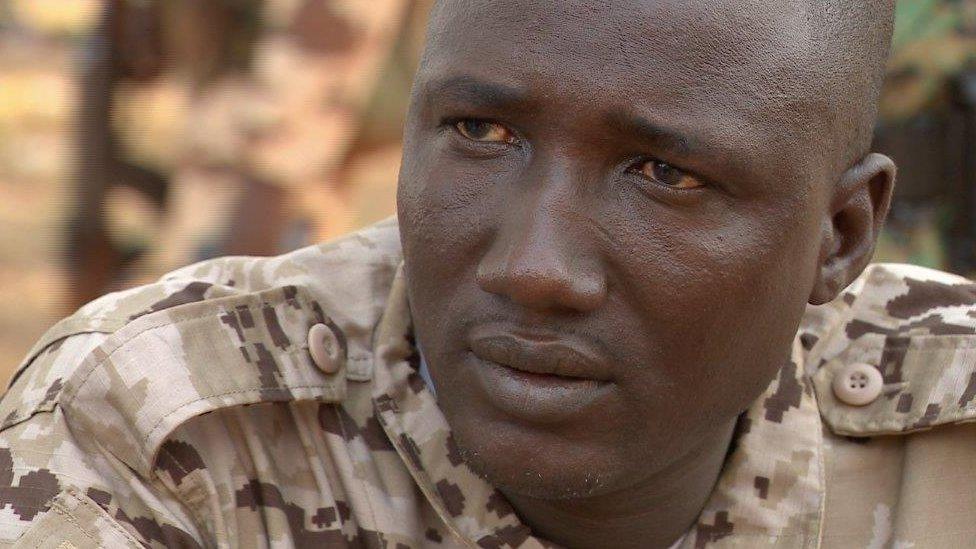

Nothing displays the limits of UN power quite like the swagger of Gen Boade's enemy, the Muslim leader of the Union for Peace in Central Africa (UPC) militia, "General" Ali Darassa, and his gun-toting army.

Gen Darassa lives directly opposite the UN headquarters in Bambari.

Like his enemy, he stands accused of sending his men on killing sprees in the surrounding countryside.

Gen Darassa, a Muslim who calls himself a protector, is in a turf war with a Christian warlord

But he has no fear of arrest by the blue helmets. Nor are they about to ask his militia to hand over the weapons they brandish during our interview.

Like Gen Boade, Gen Darassa describes himself as a protector of the people.

I put to him that there is another view, and that is that he is a ruthless killer. I caught a faint smirk as the question was translated.

His reply was delivered in a calm monotone: "If I were a ruthless killer, people could not live peacefully near me.

"I know that people are fleeing the other side to settle next to me. It is because here, there is peace; there is free circulation; there is social cohesion."

Murderous momentum

The latest fighting north of Bambari has come about because of an alliance between Muslim and Christian militias who want to dislodge Gen Darassa.

The clashes illustrate the growing complexity of the crisis.

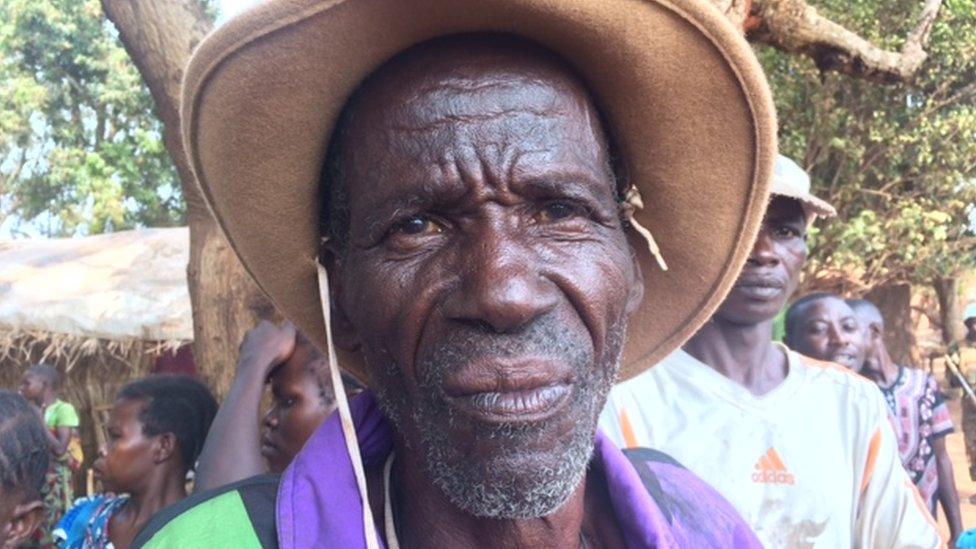

Civilians, like this displaced man, are always the first casualties of the warlords' feud

Gen Darassa is an ethnic Peul, nomadic pastoralists who are being targeted by both Christian and Muslim militias on the basis of their ethnicity.

Competition over resources, including gold, diamonds and cattle has created murderous momentum.

The UN has drawn red lines in the past and failed to enforce its will.

There is nobody more alert to weakness or disarray in the international community than the 21st Century warlord.

He has studied the UN failures in Rwanda and Bosnia and other ruined places. He has seen the resurgence of violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the struggles of the UN-backed government in Somalia.

He has concluded that until such time, if ever, that the UN uses force to stop him, he will continue to act like the real power in the land.

That means being free to kill his enemies, and the civilians who belong to that religious or ethnic group, and to plunder and extort along the roads.

Warlords summoned

The deputy chief of the UN mission is a former British diplomat, Diane Corner.

She came to Bambari to tell Gen Boade and Gen Darassa what would happen if they started fighting.

For weeks now, UN intelligence has been tracking the movement of convoys of armed men moving towards Bambari.

Diane Corner has the tough mission of keeping feuding warlords from starting a fight

The fear is of an outbreak of fighting in the town which would cause chaos for civilians.

The warlords were summoned to a prefabricated office in the UN headquarters.

They would not meet with Ms Corner together, so Gen Boade waited while Gen Darassa was told of the will of the international community.

There were no photo opportunities.

Ms Corner is a realist who understands the limits of a UN mission which must deal with complex regional politics, limited resources, uneven quality of troops, and a new occupant of the White House who believes in the mantra of "America First".

The first thing she makes clear is that the UN had not come to negotiate with the warlords - rather to remind them that the red lines would be defended.

"I reminded them that the international community was watching, and of their responsibilities towards the civilian population whose rights must be respected," she said.

Ms Corner is a relatively recent recruit to the UN. She seems anxious to confront the bureaucratic and political challenges that routinely dog peacekeeping missions.

The fact that UN attack helicopters were deployed at the weekend proves this.

Not only in the CAR, but in trouble spots across the globe there will be warlords and beleaguered civilians watching what happens next.

Read more about CAR: