'We need to talk about male rape': DR Congo survivor speaks out

- Published

Stephen was raped in 2011 during the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo

"If I talked about it, I would have been separated from the people. Even those who treated me would not have shaken my hands."

Stephen Kigoma was raped during the conflict in his home country, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

He described his ordeal in an interview with the BBC's Alice Muthengi, calling for more survivors to come forward.

"I hid that I was a male rape survivor. I couldn't open up - it's a taboo," he said.

"As a man, I can't cry. People will tell you that you are a coward, you are weak, you are stupid."

The rape took place when men attacked Stephen's home in Beni, a city in north-eastern DR Congo.

"They killed my father. Three men raped me, and they said: 'You are a man, how are you going to say you were raped?'

"It's a weapon they use to make you silent."

After fleeing to Uganda in 2011, Stephen got medical help - but only after a physiotherapist treating him for a back problem realised there was more to his injuries.

He was taken to see a doctor treating survivors of sexual violence, where he was the only man in the ward.

"I felt undermined. I was in a land I didn't belong to, having to explain to the doctor how it happened. That was my fear."

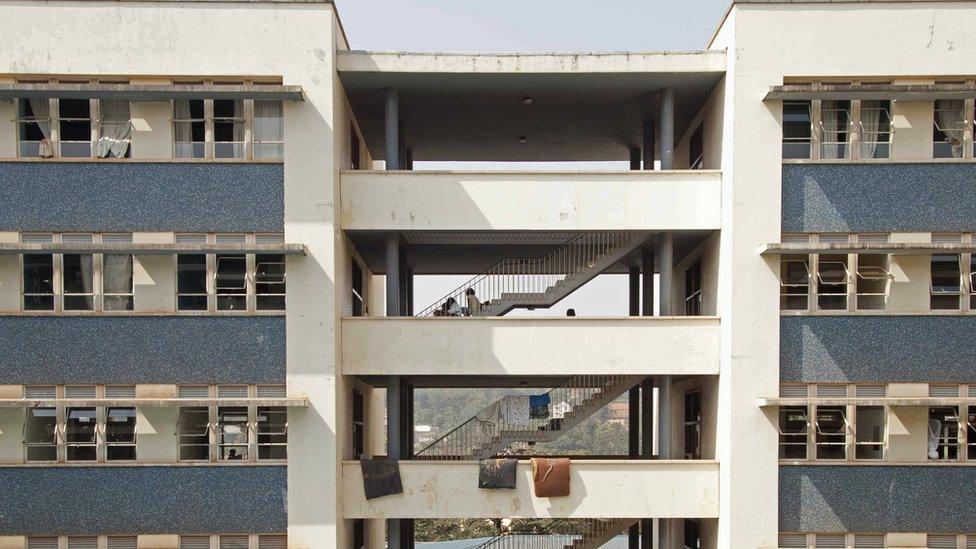

Stephen was treated at the Mulago Hospital, Uganda's biggest referral hospital

Stephen was able to get counselling through the Refugee Law Project, an NGO in Uganda's capital, Kampala, where he was one of six men speaking about their ordeal.

But they're far from being the only ones.

Police not an option

The Refugee Law Project, which has investigated male rape in DR Congo, has also published a report on sexual violence among South Sudanese refugees in northern Uganda.

It found that more than 20% of women reported being raped - compared to just 4% of men.

"The main reason that fewer men come forward is that people assume they should be invulnerable, they should fight back. They have allowed it so they must be homosexual," Dr Chris Dolan, director of the organisation, told the BBC's Focus on Africa programme.

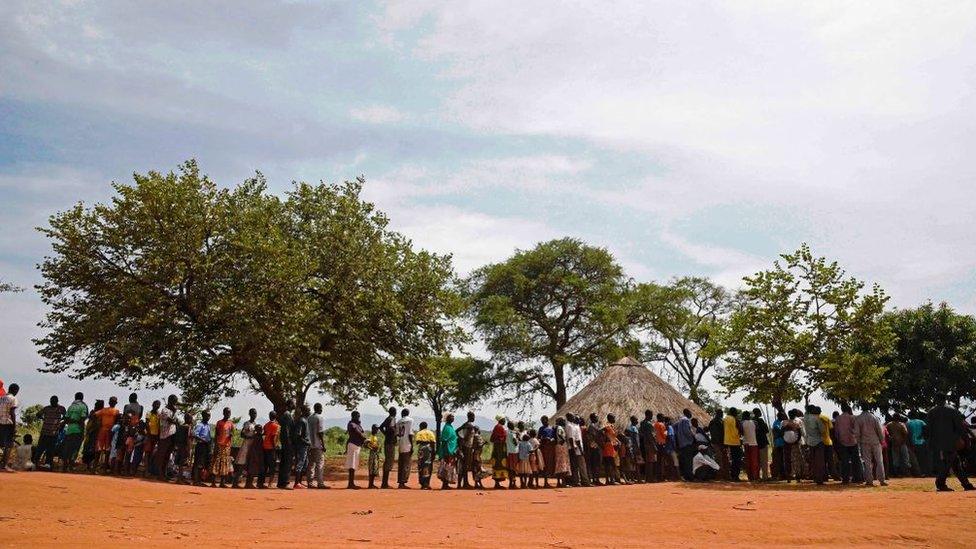

Uganda took in more refugees in 2016 than any other country - most fleeing the conflict in South Sudan

Legal challenges pose a problem when it comes to men reporting rape, he added.

"In the Rome Statute [which established the International Criminal Court] you have a definition of rape that is wide enough to include women and men, but in most domestic legislation, the definition of rape involves the penetration of the vagina by the penis. That means if a man comes forward, they'll be told it wasn't rape, it was sexual assault.

"There's the problem of criminalisation of same-sex activity - it revolves around penetration of the male body, not around consent or lack of consent."

In 2016, Uganda took in more refugees than any other country in the world, and has been praised for having some of the world's most welcoming policies towards them.

But for male rape survivors like Stephen, life there can be tough. Homosexual acts are illegal in Uganda, and going to the police to report rape is not always an option.

"When I asked the police, they said that if it has anything to do with penetration between a man and a man, it is gay," he said.

"If it happens to a woman, we listen to them, treat them, care and listen to them - give them a voice. But what happens to men?"

- Published12 May 2011

- Published19 January 2011

- Published2 June 2014