The terrible price of the search for a better life in Europe

- Published

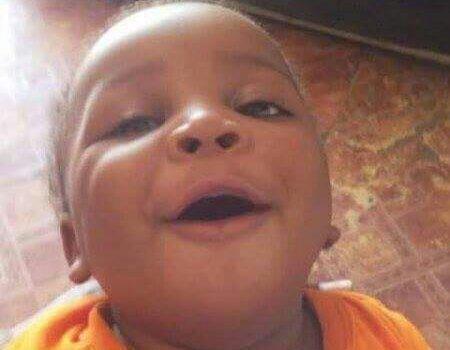

Yaya Sangare with his four-year-old daughter, Deborah

Three photos are all that Yaya Sangare has to remind him of the family he once had.

It was nine months ago when his wife and sons drowned off the coast of Libya.

"I was holding my newborn son Kami Davide in my arms when he died," he says quietly, as he goes through the small album of photos on his cracked mobile phone.

His wife Seri Dejezi and their other two sons - 12-year-old Eli and 14-year-old Elise - also died when their boat went down in the Mediterranean.

Sitting on the steps of the Piazza Garibaldi in the Napoli heat, the 38-year-old lingers over the photo of his sons.

"These boys... I love them so much."

Yaya's two elder sons Eli, 12, and Elise, 14, both drowned when the boat they were in was lost at sea

Now it is only Yaya and his four-year-old daughter, Deborah, left to pick up the pieces.

She is smiling and singing, occasionally grabbing her father's hand for attention.

Deborah was also on the boat that fateful night, but Yaya says they don't talk about it.

"I'll tell her one day what happened. She remembers sometimes. But one day I'll sit down and tell her all the stories, but not now. It's too hard."

Originally from the Ivory Coast, Yaya left during the first civil war in 2002. Crossing the desert into Mali and then Algeria, he and his young family lived in refugee camps before making the journey to Libya, where they stayed for three months.

However, Yaya had wanted to reach Europe by sea.

With its islands, and exposed coastline on either side, Italy has been the main destination for refugees and migrants. Between January and August this year, 97,000 people came illegally by boat according to the UN's International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

But the route is often a fatal one. More than 2,000 people have died in the sea so far this year.

Pope Francis has called the Mediterranean a "vast cemetery", but Yaya says he knew he was taking a risk coming here.

Yaya's son Kami Davide, who he says died in his arms

"We wanted to leave because Libya was very difficult and I wanted to make a better life for my family in Europe," he says.

He paid more than €3,000 (£2,766; $3,560) to traffickers to get to Sicily but like many endured violence at their hands. They smashed the top row of his teeth as they pushed him and his family on to one of 19 small rickety boats.

"When we got on, there were 154 people on my boat and we were all on top of each other. It was terrible," Yaya says.

The boats gave way in the night - only 19 people survived from his. Three other vessels and all their passengers vanished into the dark waters.

Yaya's eyes start welling up, his voice cracks, but he takes a deep breath to avoid crying in front of Deborah.

"I couldn't find my wife Dejezi and the boys, my heart hurt. I couldn't help them. Then I saw their bodies floating."

He and Deborah finally arrived in Sicily, with a small backpack of clothes. Just the two of them.

'Someone wanted to buy my daughter'

There is a saying in this city: "Vedi Napoli e poi muori" (see Naples and die).

It traces back to the times when the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies - of which Naples was the capital - was an affluent and prestigious part of the world.

The meaning behind the old proverb is that once you have seen the glory of Naples, there is nothing else worth seeing, but for Yaya it is very much the opposite.

"This is a bad city. There is nothing here for us. Many things have happened here."

Yaya's wife Seri Dejezi also perished off the coast of Libya

Yaya lives in a refugee centre in the city with his young daughter. They both have refugee status from the UN Refugee Agency in Liberia.

But he wants to get out, and angrily recalls a story over how a man approached him to buy Deborah.

"I'll never forget it. I got approached by a man with a phone number and was told, this man wants to buy your daughter for €30,000.

"I go to my office (refugee reception centre) and said 'see what's happened'. I gave them the number, I told them my story. I started to cry," Yaya says.

He adds that nothing was done and that the man was never caught. But he fears that eventually the city could destroy him and Deborah.

"I don't like the way some men look at my daughter. I worry she may be exploited into drugs and prostitution," he says.

As he tells his story, there are dozens of other young men and women, of African origin, congregated on the Piazza Garibaldi.

Pointing to them he says: "I don't want to live like this. I'm fearing that I'll be left in Napoli.

"I am strong enough to work but I can't get a job. I want to keep moving and take Deborah to the US or Australia."

Last week, a Catholic priest who helps refugees urged his fellow Africans not to turn their backs on their homeland.

Don Mussie Zerai said that people should think twice before making the perilous journey to Europe.

But Yaya shakes his head when I mention this: "I can't go back home. I don't like the politics there. Also I promised a better life for my family."

He says that he is focused on his plans and will only go back to get his mother and other family members.

"My mother is Christian. I get my strength from her and from God, and from my daughter Deborah. I do this all for Deborah."

- Published30 March 2016

- Published17 August 2017

- Published24 July 2023