How big game hunting is dividing southern Africa

- Published

Drifting down the Zambezi in Zimbabwe, I overheard two American men swapping hunting stories.

"First shot got him in the shoulder," a white man in his late sixties explained to his friend. "Second hit him right in the side of the head!" Pointing at his temple, he passed his phone with a picture. The animal in question was a dead crocodile.

Crocodiles are easy to find on this part of the Zambezi: lying in the sun on the banks of the river, boats can float just a few feet away. And given that they are motionless for most of the time, not hard to shoot, I imagine.

The second American showed his pal a picture of a Cape Buffalo he had killed, and planned to have shoulder mounted. He complained he couldn't afford the $19,000 (£14,500) Zimbabwe demands for the licence to kill an elephant. His buffalo cost him $8,000 (£6,100).

"Are they saying an elephant is worth more than two buffalo?" he lamented. "I saw hundreds of elephants today. Far too many. You have to see it here to realise. In California they are saying these animals are endangered!"

The first man's wife then talked of the thrill she gets at the kill, discussing how different calibres of bullet explode the vital organs of African wildlife. I left to look at the hippos watching from the river.

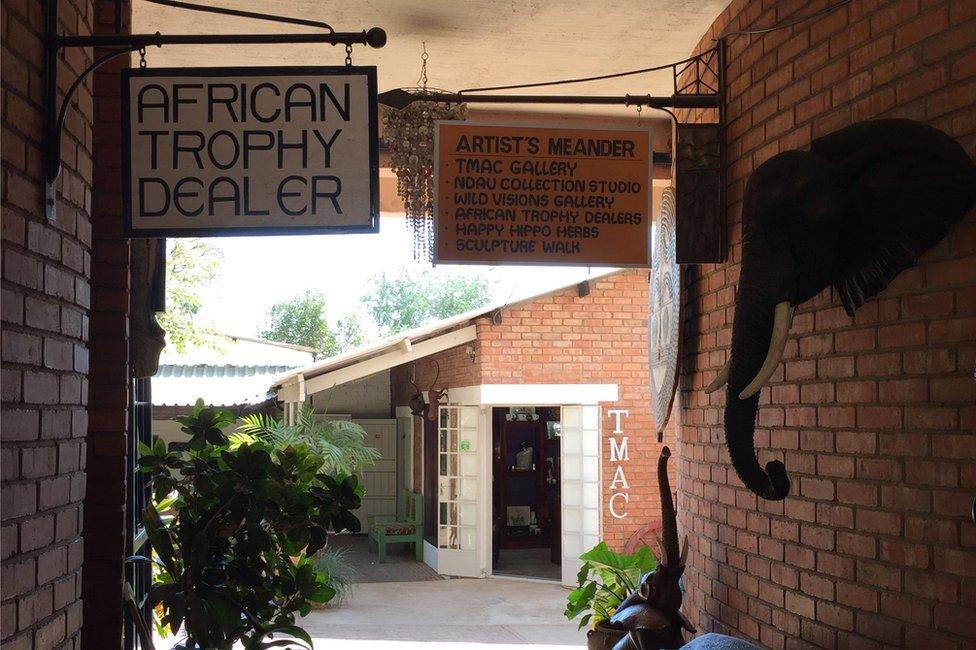

A trophy hunting taxidermist welcomes customers in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe

But, curiously, I have felt obliged to consider the ethics of big game hunting at home in London in the last few months.

I'm an Arsenal fan, and it recently emerged that my team's owner, American sports tycoon Stan Kroenke, had launched a TV channel in the UK featuring lion and elephant hunting.

High profile supporters

The corporate values of family brand Arsenal do not sit easily with pay-to-view videos of hunters shooting animals for fun, and after a couple of days of hostile publicity, Kroenke ordered his channel to stop showing the killing of some big game.

But both sides in the hunting debate claim they are the true guardians of animal welfare.

Supporters of African trophy hunting, including some in very high places - two of President Trump's sons are avid big game hunters - argue that a ban on hunting would harm wildlife and local people.

It would stop much needed revenue reaching some of Africa's poorest communities, discourage conservation and cut funds for wildlife management that would make it easier for poachers to operate, they say.

Opponents counter that little of the profit from trophy hunting money ends up in the communities where it takes place. They say poachers use legal hunting as cover for their illegal activities, and argue that there are more efficient and humane ways to support the welfare of southern Africa's animals and people.

I was travelling in Zimbabwe and neighbouring Botswana last month - two countries with opposing policies towards big game hunters. Hunting is still big business in Zimbabwe, as the rich Americans on the Zambezi demonstrate, but since 2014 it has been completely banned in Botswana.

Majestic animals

The difference in approach between Botswana and its neighbours - South Africa, Namibia and Zambia also allow trophy hunting - was brought dramatically home to me in the country's glorious Chobe National Park.

In the late afternoon, I watched a herd of around 600 Cape Buffalo snake its way down to the Chobe River that marks the boundary with Namibia. It was mesmerising to see these majestic animals following each other, nose to tail, across the water.

Cape Buffalo cross the Chobe River from Botswana into Namibia where hunters are waiting

Then my guide pointed out two vehicles on the horizon, across the river. "Hunters," he explained, simply. Through the binoculars we could see six men with rifles. Apparently oblivious to the risk, the buffalo continued to cross the border towards them. Later, shots would be heard.

In a move interpreted as a direct challenge to the wildlife policies of other southern African nations, Botswana's President Ian Khama is marching his country towards a new model of African tourism: "low impact/high value".

Botswana believes that by protecting its animals and minimising humankind's footprint on the natural world, it can turn the country into an exclusive tourist destination that brings in far more than it loses from the ban on hunting.

Hostile environment

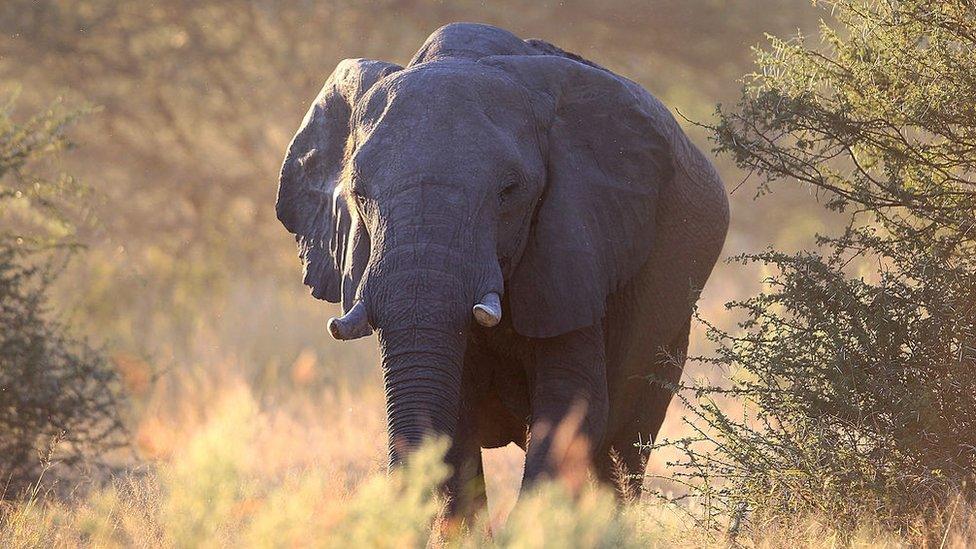

Botswana is home to more than a third of Africa's dwindling elephant population, and - since the hunting ban - these intelligent animals have increasingly sought refuge there.

The concentration of elephants is a huge draw for tourists but, as predicted by opponents of the ban, it is also a huge temptation for less scrupulous hunters and poachers.

Botswana's answer is to make the country a hostile environment for those who want to harm the wildlife.

Military bases have been moved to the borders of the national parks. Armed patrols on foot and in the air are ready, if necessary, to kill people coming to kill animals. Some poachers have been shot dead.

The hunting ban doesn't just apply to rich trophy hunters.

It also limits or outlaws the shooting of game by local people for food or to protect crops and livestock. The Botswana government believes if there is any legal shooting of animals, the big poaching syndicates and illegal hunting operations will use that as cover for their activities.

Farmer Chibeya Longwani shows me his bucket of tabasco chillies

In Mabele village, close to the Namibian border, I watched a man mixing an extraordinary cocktail: crushed tabasco chillies, elephant dung and engine oil. With a flourish he set the contents on fire and stood back to admire his handiwork.

"That is supposed to stop an elephant trampling my crops," Chibeya Longwani told me, pointing at the ash in the tin.

Compensation

He spread it along the sides of his field, beside plastic chairs, broken electric fans and beer crates, as instructed by the Ministry of Agriculture.

"They said that bees stop elephants too," Mr Longwani said. "But they don't have the boxes at the moment." His frustration was obvious.

As well as advice on deterring elephants, farmers can claim compensation from the government if wild game does damage property. But if they kill the animals, they are likely to get nothing.

Plastic refuse is used to try and deter elephants from farmland

To police the new approach, the Department of Wildlife and National Parks has recruited an army of Special Wildlife Scouts, operating in rural villages. Their job, for example, includes ensuring families don't take more than the five guinea fowl they are allowed each day, and that farmers are honest in their compensation claims.

It is a nationwide exercise in social engineering - trying to change the ancient relationship between the rural population and the wild animals around them. The government believes the long-term rewards justify the rules. Many farmers remain unconvinced.

For those tourists coming to Botswana with cameras rather than guns though, the policies have created an utterly captivating wild landscape teeming with amazing African animals and birds. And "elite travellers" are prepared to pay big money for the privilege of seeing it.

Anti-poaching initiatives

During the high season, a single room in one of the most exclusive lodges on the Okovango Delta can cost more than $5,000 (£3,830) a night, equivalent to the price of a Namibian licence to shoot a single leopard.

Many tourist lodge operators work in partnership with local villages. I encountered one lodge where 10% of the business turnover will soon go to the community nearby. Villagers often have a direct say in development plans.

There was a huge backlash after the much-loved Zimbabwean lion Cecil was killed in 2015

International tourism is expected to bring in $210m (£160m) to Botswana this year, rising to $370m (£280) by 2021 - more than trophy hunters spend across the whole of southern Africa.

Many in Zimbabwe, by contrast, see hunting as an inextricable part of Africa's cultural heritage, believing that, if done sustainably and responsibly, it can be a valuable addition to the region's economy and wildlife management.

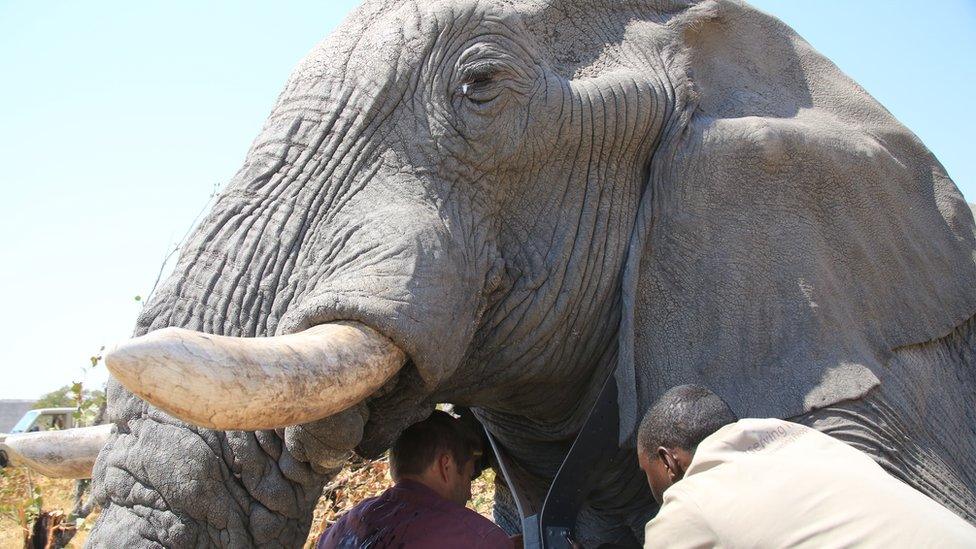

The walking guides who take tourists into the bush there aren't allowed to operate until they have passed a state exam that includes shooting an elephant and a buffalo. I asked one guide how he had felt about doing it. "It depends if you like hunting," was his enigmatic reply.

The Zimbabwean government argues that 75% of proceeds from trophy hunting goes towards wildlife preservation and anti-poaching initiatives.

Toxic impact

The recent Great Elephant Census project, external suggests Zimbabwe's elephant population has fallen 11% in a decade, with poaching and illegal hunting threatening to wipe out whole herds in parts of the country.

The killing of Cecil the lion by an American trophy hunter just outside Zimbabwe's protected Hwange National Park area in 2015 made headline news around the world.

The furore prompted a number of airlines to ban the transport of "trophies" from Africa, another sign of how toxic hunting has become for international brands.

Three years after introducing its hunting ban, Botswana is so far holding firm, despite huge pressure from other southern African nations.

It is a critical time for the policy. Any stumble, and the hunters are waiting on the horizon.

- Published21 July 2017

- Published19 July 2017

- Published11 November 2016

- Published2 October 2016

- Published25 September 2016

- Published31 August 2016

- Published29 July 2015

- Published29 November 2012