Libyan migrant detention centre: 'It's like hell'

- Published

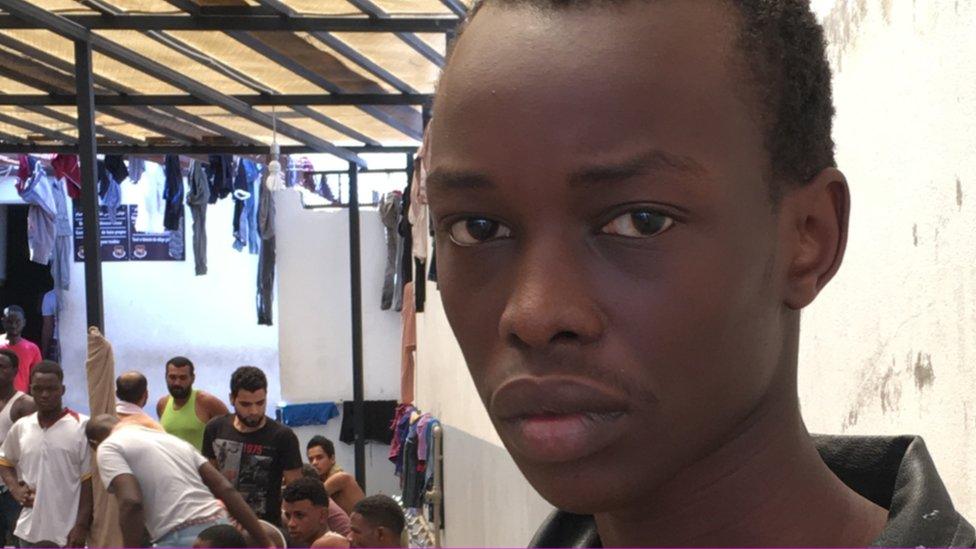

Detainee Hennessy: "I feel like a dead person"

Hennessy Manjing expected the worst at sea.

The 18-year-old from South Sudan knew he might perish on the treacherous crossing from Libya to Europe. So far this year, the Mediterranean has claimed an estimated 2,400 migrants and refugees.

But before he ever reached the shore, Hennessy was kidnapped, beaten and almost shot.

The teenager says he left home in 2016 after family problems resulted in death threats.

He is behind bars in the Triq al-Sika detention centre in Tripoli, along with around 1,000 other men. Most we met were Africans in search of work, who were stopped at sea, or trying to get there.

Now they are jammed into a warehouse, bereft of light and struggling to breathe.

Hennessy Manjing spent three years in London, where he wants to return

In the sweltering heat they are melding together - a tapestry of jumbled limbs, and torment.

"When they find their journey ends here, they are completely broken," said one official at the centre.

Some try to fan themselves with scraps of cardboard. At night, when the doors are locked, they have to urinate in bottles.

"It's like hell," said Hennessy "even worse than jail."

'I thought I had been shot'

The gaunt teenager spoke with a London accent - the legacy of three years spent living in the UK with his family.

Hopes of getting back there led him first to Egypt, and then across the border to eastern Libya. He says that's where an armed gang kidnapped him and about 40 others from their trafficker.

There is not enough money to look after all the detainees

"We saw people holding guns and sticks, and they forced us into trucks," he said.

"People starting jumping off. By the time we jumped, there was an old man, from Chad. He was shot. Blood went all over my T-shirt. I thought I had been shot as well so I just ran away."

He sought help from a local man, who returned him to one of the kidnappers.

"He slapped me and punched me in the stomach, and said: 'Why did you run away?'

"Thank God, on the third day my trafficker came and released us."

Inside a Libyan migrant detention camp

Hennessy was given a fake visa to fly to Tripoli, but on arrival he was arrested by a militia and taken to a detention centre near the airport.

"There were daily abuses," he said. "If people make noise, or rush for food, you get beaten."

The weapon of choice for the guards was a water pipe.

Some of his fellow detainees outlined other hazards on the migrant trail through Libya - being bought and sold by militias, used as slave labour, and forced to bribe guards to be released from detention centres.

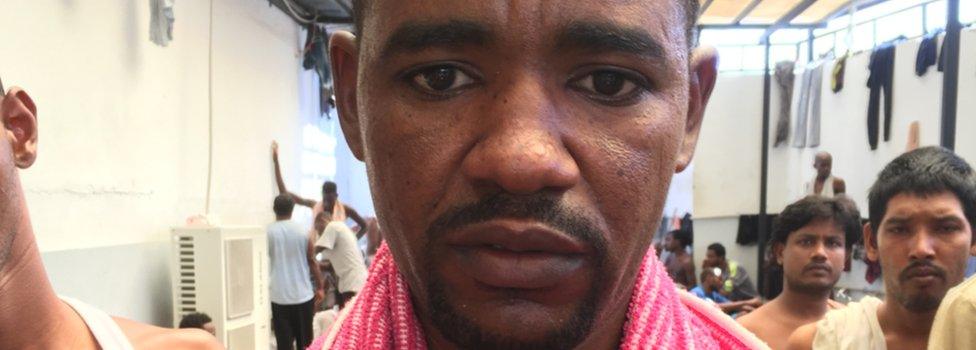

Osman Abdel Salam:

I just want to leave this place and go to my country

Osman Abdel Salam, from Sudan, lifted the red towel around his neck to reveal a raised scar.

He said that was the handiwork of jailers in the Libyan town of Bani Walid. They forced prisoners to call home, while being brutalised, to extort money from their relatives.

"When we call, we are crying. They beat you on the head. There are some people who don't want to obey - they burn their body. My father is a farmer. He doesn't have money so he sold our house."

Osman's freedom - which was short-lived - cost his family $5,000 (£3,800).

When I asked if he still wanted to get to Europe, he covered his eyes with the towel and began to weep.

"I just want to leave this place and go to my country."

'Horrible moment'

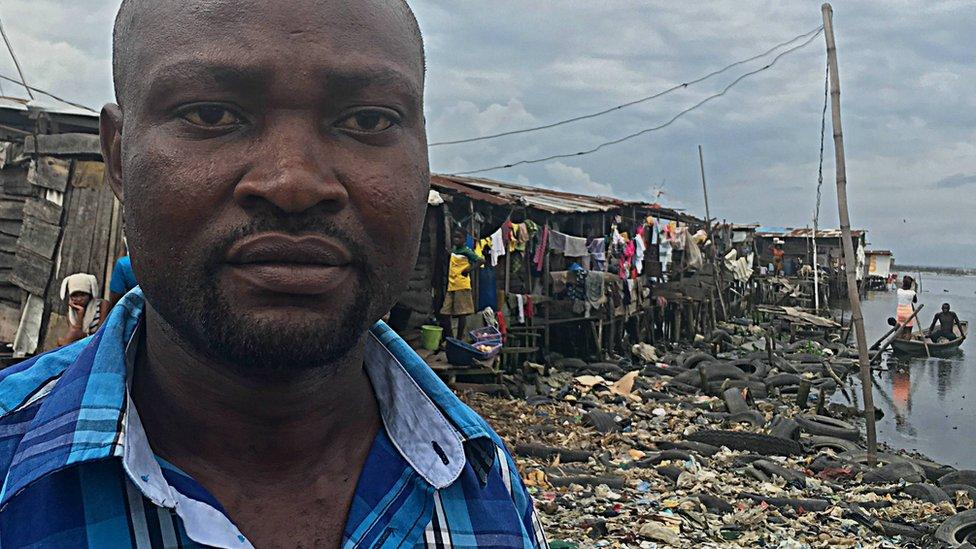

Emmanuel John, an 18-year-old who speaks perfect English, said he was beaten from the moment he crossed the border, and feared he would die.

"The smugglers that brought us to Libya handed us to others, from the same network," he said.

"There are stops along the way until you arrive in the city. At every stop you have to pay money. And if you don't, there will be beatings."

But it was not the physical abuse that pained him the most.

"Two girls were raped in the room beside us," he said.

"It was a horrible moment. We couldn't do anything. We didn't have anything to defend ourselves."

He told us the girls were aged about 15 and 19, and were travelling with their family.

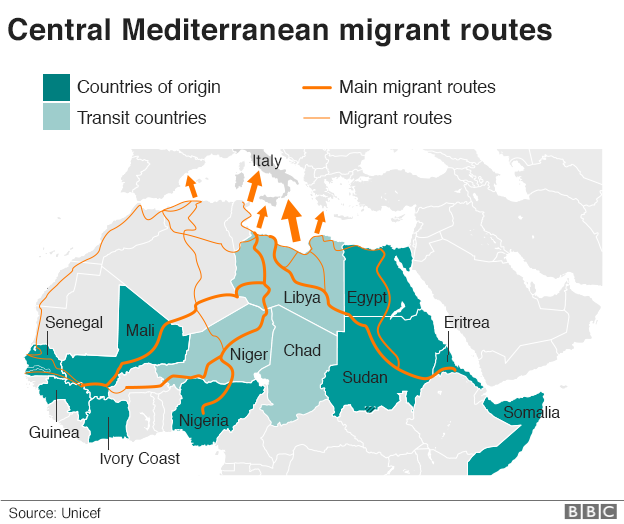

The European Union wants Libya to do more to prevent migrants like Emmanuel reaching Europe.

But those intercepted by the Libyan coastguard are being returned to an unstable country, with a collapsing economy, that can barely feed them.

A recent United Nations report condemned the "inhuman conditions" in Libyan detention centres highlighting "consistent reports of torture, sexual violence and forced labour", and cases of severe malnutrition.

Dreaming of being deported

Breakfast time at Triq al-Sika was long on queues, and short on food.

Each man received a small bread roll, some butter, and a single cup of watery juice.

Three-month-old Sola has been in detention for most of his short life

The detainees wanted us to witness this, as did the officials in charge. They say they have run out of money to pay their suppliers and are now relying on donations.

Those behind bars here are effectively prisoners, who don't know their sentence. They can be held indefinitely - with no legal process. Their only hope of release is to be sent back to their home country.

Three-month-old Sola has been in detention for most of his short life.

We found him in the women's section, sleeping peacefully on a faded mattress.

His young mother, Wasila Alasanne, tried to take him across the seas to Italy when he was just four weeks old.

"Our boat broke and the police arrested us on the water," she said.

"Since then we have been in five prisons. We don't have enough food. We don't have the right to call our parents. They don't know if I am alive or dead. My baby and I are suffering."

Wasila's husband is being held in a different detention centre.

She has no idea when they will be reunited, or when they will free.

Her home country, Togo, has no ambassador in Libya.

Now she can only dream of deportation, as she used to dream of Europe.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published23 January 2020

- Published28 April 2017

- Published21 June 2017

- Published17 July 2017

- Published8 July 2017

- Published6 July 2017

- Published6 July 2017