Sudan US sanctions: Cancer patients and businesses hopeful

- Published

Hawa Mohammed Adam's fans, friends and family paid for her cancer treatment abroad

Sudanese music star Hawa Mohammed Adam hopes the lifting of US trade sanctions means she will no longer have to travel to Egypt to receive life-saving treatment for cancer.

She was diagnosed with breast cancer last year and her extended family, friends and fans raised the money to send her to Cairo.

Her cancer initially spread because old scanning machines in Sudan had failed to detect the seriousness of her condition.

"I discovered that I did not only have one tumour, but several tumours," says the musician, who also teaches piano at the University of Sudan and is looking forward to returning to work.

"Despite the fact that that we have very competent doctors, we do not have devices, equipment and tools. We do not have anything."

'Easy to destroy, harder to build'

The legacy of more than two decades of sanctions is most visible when you drive through the industrial area of Khartoum North city.

The streets are lined with abandoned, boarded-up factories and the skeletons of dumped machinery.

Twenty-five years ago, the Kobani factory used to produce 100 tonnes of groundnut and sesame oil a day.

But for the past five years it has not made a drop, as the company was unable to import spare parts from Europe because of trade embargoes.

A dozen buses that used to transport Kobani's more than 100 employees are lined up outside the factory, their shattered windscreens and flat tyres watched over by the only remaining employee - the security guard.

Many factories have fallen into disrepair

"Only 40% of the factories in Sudan are functioning - and those are only operating at 20% capacity," says Motalib Dirar, director of Amgad Tomorrow Enterprise, who started his import-export firm in the 1970s.

He is excited by the prospect of new business opportunities after the US government's announcement on 12 October that most economic sanctions were being lifted.

They were imposed in the 1990s for harbouring fugitives such as al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden, and included the freezing of all Sudanese government assets in the US and a ban on Washington's allies trading with Khartoum.

However, Mr Dirar's optimism is tempered by the realisation that "it's easy to destroy" but much harder to rebuild.

Sanctions 'absorbed people's anger'

Officials in Washington say their decision was influenced by Sudan's improved human rights record and its co-operation in the fight against terror.

President Omar al-Bashir, who seized power in a 1989 coup and has won several elections since, is still subject to an arrest warrant by the International Criminal Court (ICC). He denies the charges of ordering a genocide the country's western Darfur region.

But the US believes working with the government is more productive than continuing isolation.

"We want Sudan to be a partner and an ally, not an adversary or a negative force," says Steven Koutsis from the US embassy on the outskirts of Khartoum.

Most students at the University of Khartoum have only known life under sanctions

Sudan's Deputy Prime Minister Mubarak Elmahdi acknowledged that the government had "seized the chance of the geopolitical changes", especially over the West's worries over illegal immigration and terrorism, to secure better relations.

Sudan does remain on the list of state sponsors of terror, which means Khartoum will not yet be able to purchase US weapons and also faces restrictions on access to US aid.

But the move effectively ends Sudan's isolation from the global financial system.

More on Sudan

However, Mohamed Eljak believes the economy is in a mess because of chronic mismanagement by a government that favours "the rich rather than the poor".

The academic also says the cost of war is a major factor behind the economic hardship.

More than 70% of the annual budget is spent on the military and security, which has been "devastating for the economy", he says.

Sudan has fought multiple rebellions for decades including in Darfur, Blue Nile and South Kordofan, as well as the war with South Sudan before it seceded in 2011. While Khartoum says it has made efforts to resolve these conflicts, the main rebel movements remain active and the prospects for renewed violence are high.

The government blames sanctions "to absorb the anger of the people", Mr Eljak says.

He works at the University of Khartoum, which has been home to some of the strongest government critics, in a country where free speech is limited.

Some students, who have only known life under sanctions, agree with his analysis.

The lifting of sanctions may give Sudan's tourism industry a boost

"The problem is not sanctions, the problem is our government," says Sadig, sitting in front of the university's library drinking tea with four friends and speaking under the watchful eye of our government assigned security adviser.

His friend Nazer adds that the "disease" in Sudan is "corruption".

"The government people will use the benefits that come from the US to improve themselves," he says.

Desert wonders

But the lifting of sanctions could be a boost for tourism - the country has more pyramids than its neighbour Egypt.

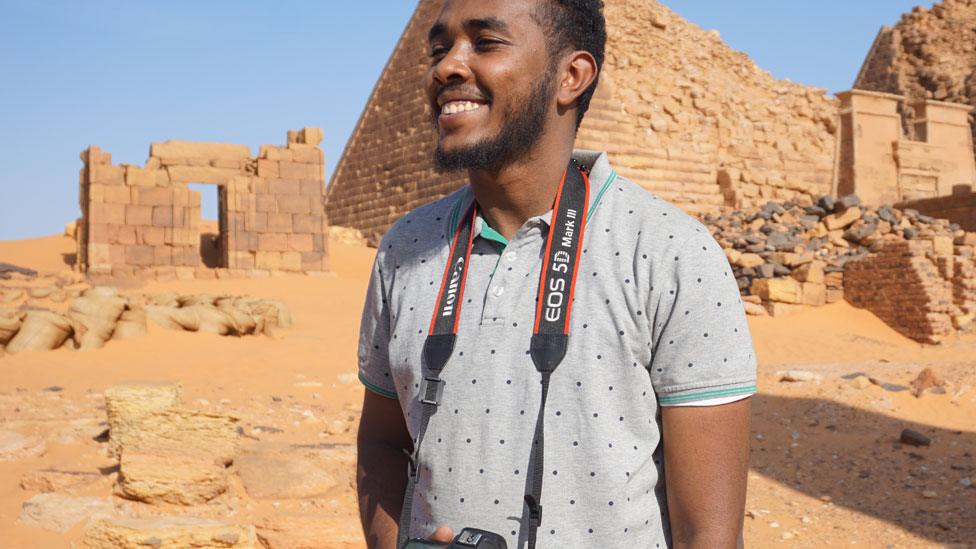

As dawn breaks over a cluster of Nubian pyramids in Meroe, three hours' drive north of Khartoum, five young men in their early 20s clamber up the dunes armed with GoPro cameras.

Some feel ending sanctions is a chance to show a different side of Sudan to the world

"We came here to see our history. You have to see it with your own eyes before you tell it to other people," says Mohammed Abdalla, who like many of his friends grew up in one of the Arab Gulf countries and only returned to Sudan five years ago.

They are keen to show off the ancient wonders of the desert and showcase a different side to the country to the world - away from bombs and war.

The friends also want the lifting of sanctions to usher in some things they enjoyed while living abroad.

"We hope we'll get a Big Mac," two of them say in unison.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external and on Instagram at bbcafrica, external.

- Published14 February 2017

- Published7 December 2015