George Weah: From footballer to Liberia's president

- Published

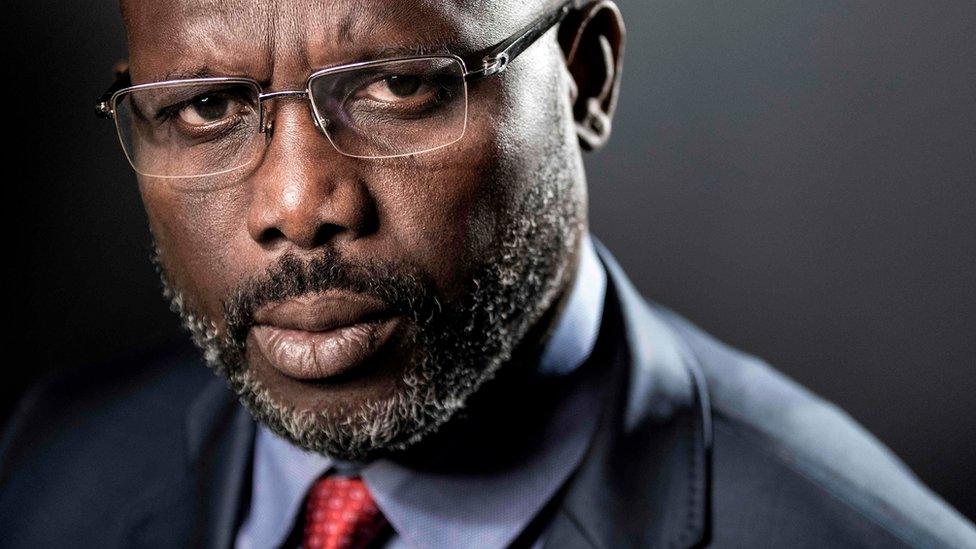

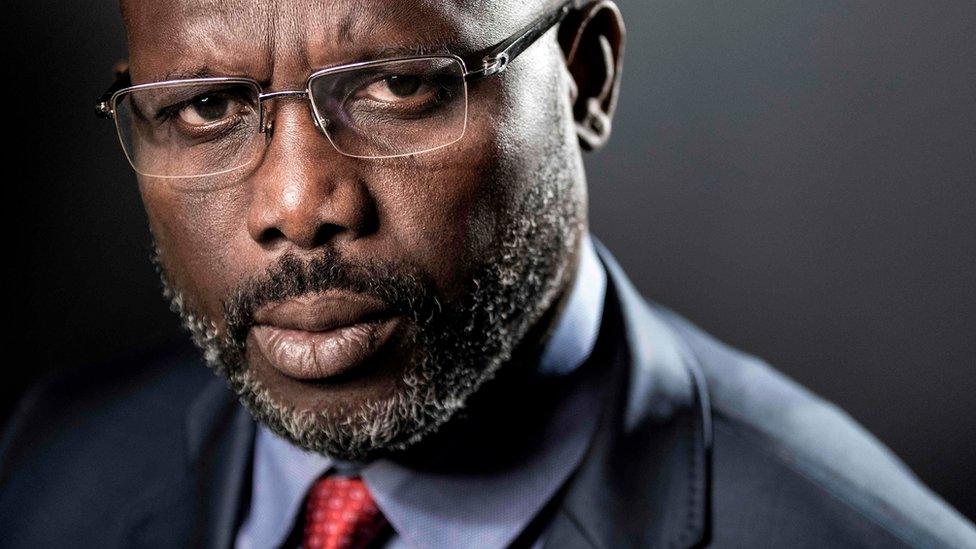

George Weah, 51, leads the Congress for Democratic Change (CDC)

George Weah has lived a life in three acts.

It has seen him move from a childhood in the slums of the capital Monrovia, to Europe's most famous football pitches and now president of Liberia.

So how did the man known as "King George" to his supporters come to get Liberia's top job?

Growing up

It will take you less than half an hour to drive between Clara Town, the slum where Mr Weah grew up, and the Executive Mansion.

And yet, they are a world apart.

Mr Weah was sent to Clara Town - an area built on a swamp and beset by disease and overcrowding - to live with his grandmother by his parents, who lived in south-eastern Grand Kru County, one of Liberia's most under-developed areas.

This less-than-auspicious start is one of the things which makes him such a hero to his supporters.

George Weah: The football legend who became president

"Weah is grass roots, a son of the soil - he is a star, but he has the country at heart," Oliver Myers, an unemployed 39-year-old from just outside Monrovia, told news agency Reuters this year.

It was Mr Weah's talent and determination which gave him a route out of Clara Town. As a teenager, he began playing league football in Liberia, eventually dropping out of school in his final year to concentrate on the sport - a decision that led to riches but which would come back to haunt him almost two decades later.

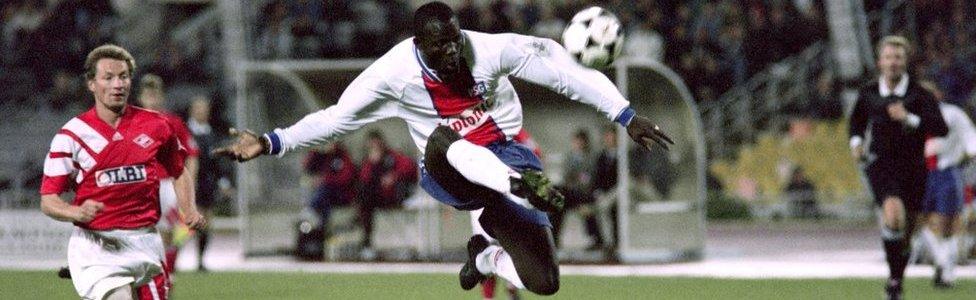

Football star

Mr Weah's life changed forever when, aged 21, Arsene Wenger spotted him playing for a team in Cameroon.

The manager brought him over to Europe, where he would play for AS Monaco. From there, it was on to Paris Saint Germain, AC Milan, Chelsea, Manchester City and Olympique Marseille.

Seven things about George Weah:

Born 1 October, 1966, grew up in a slum in Liberia's capital

Signed by Arsene Wenger to Monaco from Cameroonian club Tonnerre Yaoundé

Made Monaco debut in 1987, went on to play for AC Milan, Paris Saint-Germain and Chelsea

Only African to win Fifa World Player of the Year

First ran for president in 2005, losing to Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Graduated with a business degree from a US university after being accused of lacking education

Elected president in December 2017

Along the way, the Liberian would pick up a cabinet-full of accolades, winning both Fifa World Player of the Year and the Ballon d'Or in 1995.

But he never forgot his home country, by then tangled in a civil war which would claim about 250,000 lives.

He often paid out of his own pocket for the cash-strapped national football team to travel to matches abroad. A passionate musician, he also joined up with fellow African stars to produce a song to discourage wars in Africa.

He would turn to music again years later, in 2014, when he and a popular Ghanaian musician would produce a song to create awareness about Ebola.

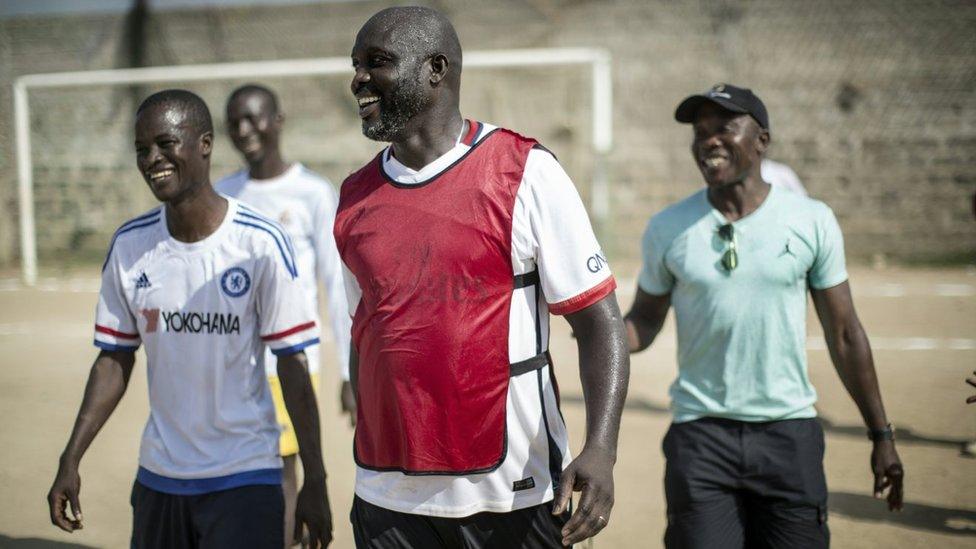

George Weah playing football in Monrovia in 2016

These small acts are still remembered today.

"The heart George has for Liberia is unbelievable," former teammate Thomas Kojo told Reuters. "He made sure the national team was always trying to bring [home] some pride."

Mr Weah dipped his toe into the world of philanthropy, becoming a Unicef ambassador, and political networking before he hung up his football boots.

Former President Charles Taylor, who stepped down in 2003, suspected Mr Weah was after his job when the footballer refused to remove his sunglasses in the president's presence - seen as a sign of the utmost disrespect.

Perhaps he was right. Mr Weah formed the Congress for Democratic Change (CDC) ahead of the 2005 election, and ran as their presidential candidate.

Weah's final game

The BBC's Jonathan Paye-Layleh on the footballer's ambition

I realized the last goal George Weah wanted to score was getting to this country's presidency during a short conversation I had with him in 2004 in Monrovia.

He was still Unicef's goodwill ambassador and was being used to encourage ex-combatants to abandon the path of war and go to school; I was part of a press team that accompanied Weah and a Unicef delegation to the central region to talk to former combatants there.

We were back in Monrovia and Weah was giving a news conference at the Unicef office; he was posing and talking more like a politician now than a footballer we knew him to be; then the conference was over and he invited me into a room.

"Mr Paye-Layleh," he said, "it is about time for us the young people in this country to think about leading the country."

Weah stopped short of saying he had that ambition but from the tone I could tell he had.

So I was not surprised when a year later he was in the race for the presidency.

But while the people may have loved him, his critics did not.

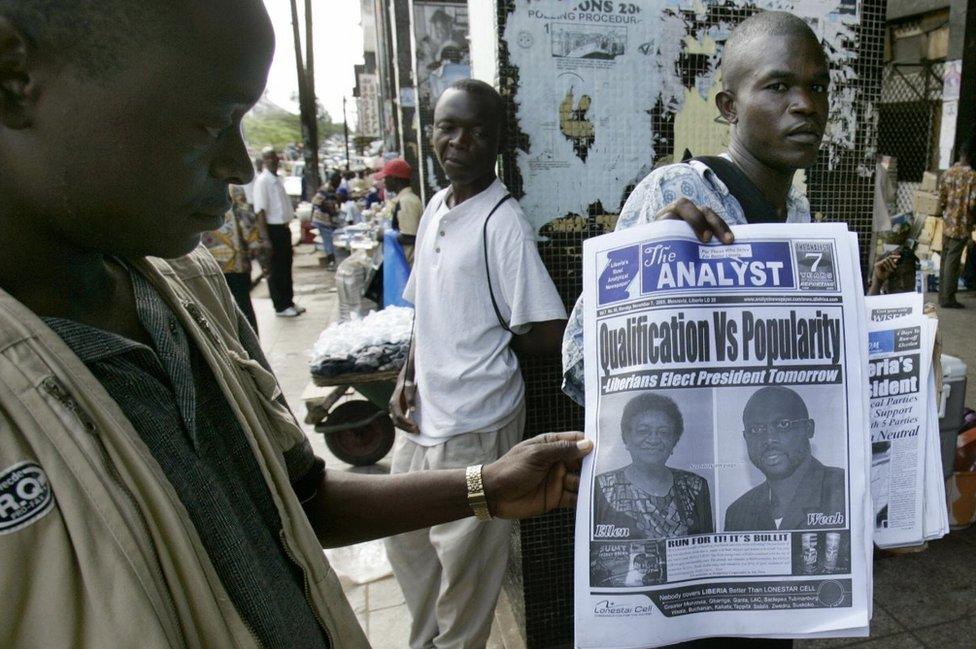

Up against the Harvard-educated Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Weah's lack of a high school diploma, along with his political inexperience, made him an easy target.

"Qualification vs popularity" roared one paper's front page on the eve of the 2005 election.

The 2005 election saw him battle Ellen Johnson Sirleaf in the second round

On this occasion, qualification won: Mrs Sirleaf was elected.

But Mr Weah - described by the BBC's Jonathan Paye-Layleh in Liberia as a moody man, who only only grants press interviews when he wants to speak his mind - was still determined to one day be elected leader.

In 2007, he revealed he had finished high school. Four years later, he graduated with a degree in business management from DeVry University in Florida.

The same year, he ran - unsuccessfully - for vice-president.

His popularity has stayed high over the course of the intervening 12 years

Success finally came in 2014, when he was elected as senator for the western province of Montserrado, which includes the capital Monrovia.

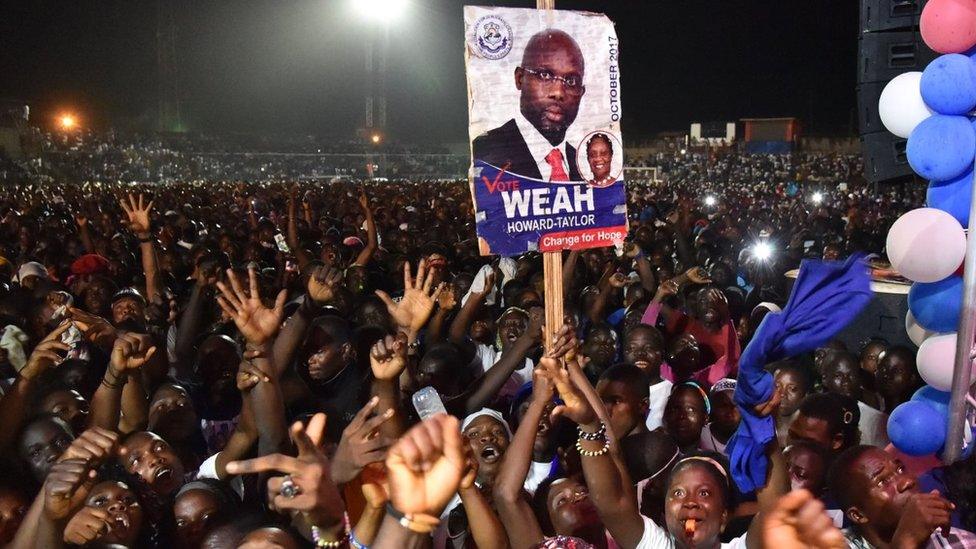

His April 2016 announcement that he would make a second bid for the presidency was met with cries of "George Weah is the man we want, George Weah is the man we want".

Ever since, the father-of-three has inspired the crowds with talk of economic empowerment for the masses, drawing on his own, poverty-stricken background, and dismissing his opponents' claims that, at 51, he remained too politically inexperienced to lead.

"When I embarked on my journey as a professional soccer player, I heard the same negativity," he told a crowd in Monrovia in August, according to AllAfrica.com, external. "Many critics said that I wouldn't make it. Many suggested that I would be a failure, but I didn't listen to them.

"I kept pushing and defying all odds until I succeeded as one of the greatest soccer legend the world has ever produced. Today, those that said I was going to be a failure are now calling me 'Chief'."

With his political ambitions fulfilled, his critics will now have to get used to calling him "Mr President".

- Published22 January 2018

- Published29 December 2017

- Published6 October 2017

- Published6 October 2017

- Published13 February 2024

- Published22 January 2018