George Weah: Footballer-turned-president faces his toughest challenge

- Published

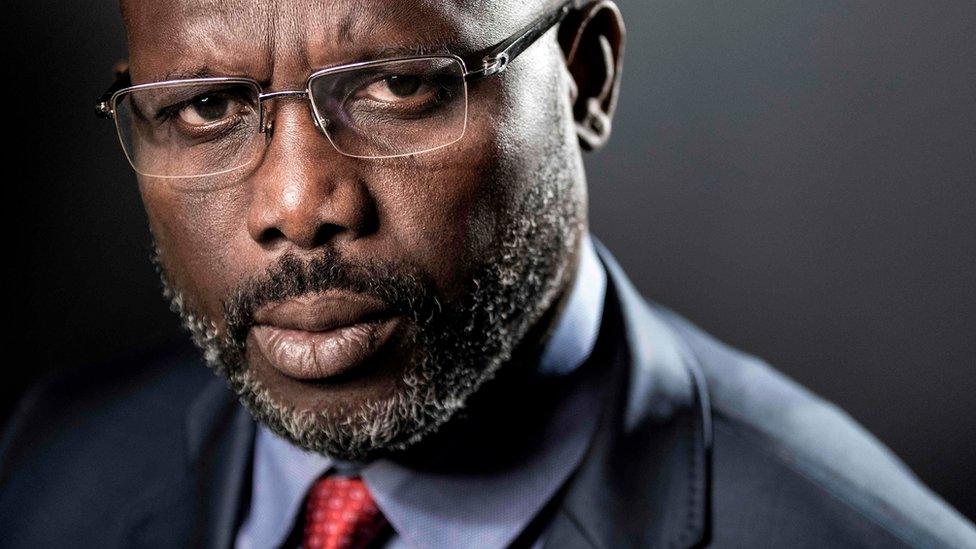

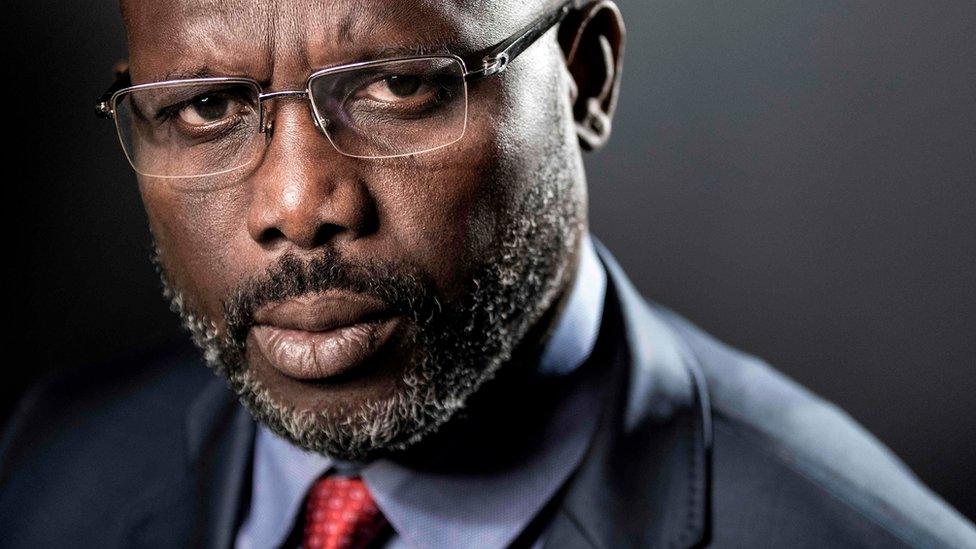

Mr Weah says he can be successful as president

An inspiration on the pitch, Liberia's new president George Weah could struggle to meet expectations off it, writes Fergal Keane.

An army band is playing on the far side of the field, the jaunty strains of ragtime float through the dead heat of the morning.

It is Monrovia in the dry season and we are gasping, airless under the climbing sun and waiting for President-elect George Weah.

When he arrives the former professional footballer is dressed in the red kit of the George Weah All-Stars and is preparing to lead a team of his friends against a selection from the armed forces.

When I last visited Liberia in 2003, the warlords and military men had made the country a byword for anarchy.

Desperate civilians were piling their dead in front of the US embassy to try to force an international intervention.

Now, at an army base in the capital, I am watching a democratically elected leader stroll out on to a football pitch to play against soldiers, who clearly hold him in awe.

George Weah, Liberia's new president, takes on his army's team

For the first time in over 70 years, Liberia is experiencing the peaceful transfer of power from one elected leader to another.

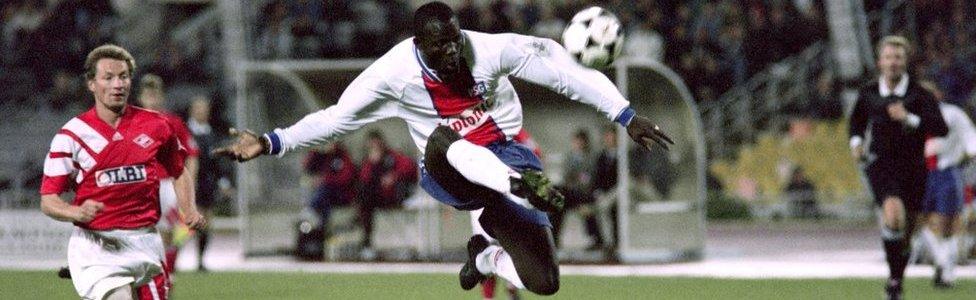

Mr Weah made his name as a star of European football at clubs like Monaco, Paris Saint-Germain, AC Milan, Chelsea and Manchester City.

For much of this time his home country was consumed by vicious civil war. Fourteen years after the war ended, and after a previous failed attempt, George Weah eventually triumphed in presidential elections last October.

Seven things about George Weah:

Born 1 October, 1966, grew up in a slum in Liberia's capital

Signed by Arsene Wenger to Monaco from Cameroonian club Tonnerre Yaoundé

Made Monaco debut in 1987, went on to play for AC Milan, Paris Saint-Germain and Chelsea

Only African to win Fifa World Player of the Year

First ran for president in 2005, losing to Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Graduated with a business degree from a US university after being accused of lacking education

Elected president in December 2017

Halfway across the pitch I manage to intercept Mr Weah with a question. Could he ever hope to be as successful a president as he was a footballer?

There is a note of impatience in his response.

"You only look at me as a former footballer but I'm a human being," he says. "I strive to be excellent. I can be successful. I was successful before in my career.

"When I left here people asked me the same question: 'Will you be successful in Europe?' I told them that when I work hard and believe in what I believe in, I show I can persevere.

"I believe that with the help of the Liberian people I will be successful."

"I strive to be excellent," says President-elect George Weah

Most people I meet here in Monrovia want to believe in the idea of George Weah as national saviour.

Returning here after 14 years, the contrast with the desolation of the past is striking.

Long gone are the boy soldiers and their ruthless commanders who struck fear into us at roadblocks. Instead bands of young people are busy sweeping rubbish from the streets ahead of the inauguration.

'We are proud of our country and our neighbourhood. We want it clean," a woman called Rose tells me.

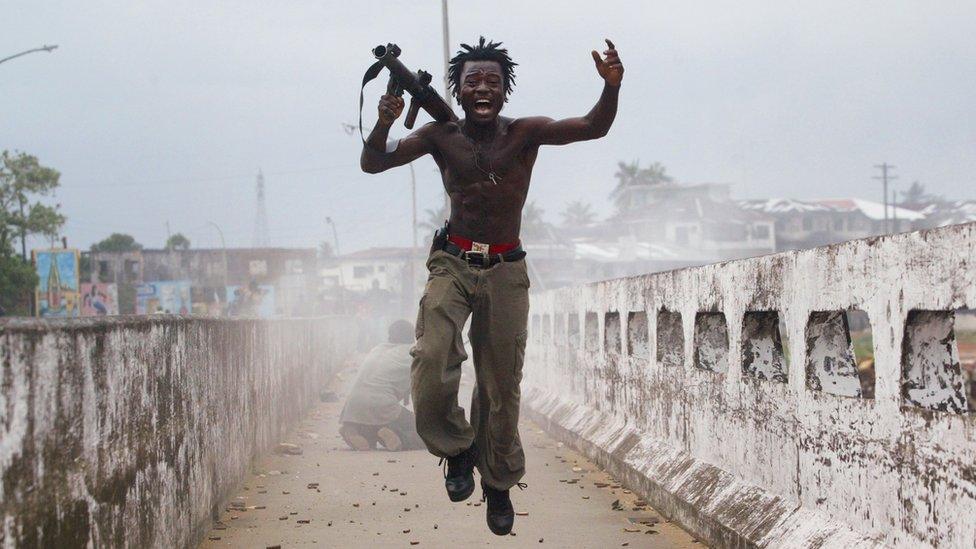

A former child soldier, Joseph Duo, immortalised in a photograph which showed him exultant in the middle of battle, believes Mr Weah is the "best hope we have to have change in this country".

Joseph Duo was a child soldier during the Liberian civil war

Mr Duo, seen on the same bridge in Monrovia, now works for the city council

Mr Duo is now a father of five children and works for the city council. I find him at home one evening, busy helping his two youngest children, a boy and a girl, with their homework.

"The memories of war still keep me awake at night," he says. "But my children don't know war and they will never know war. That is my hope."

Joseph's preoccupations now are education and employment. His eldest son Blessing, aged 22, has no job, and little hope of finding one in one of the world's poorest economies.

An estimated 63% of Liberians live below the poverty line. The campaign group, Transparency International, describes corruption as "endemic and permeating most sectors of society".

Driving through Monrovia I regularly spot stickers with the plaintive message: "Don't bribe the police".

George Weah has come to power promising to fight corruption, revolutionise education and healthcare and create tens of thousands of jobs.

This has created a huge sense of expectation. Time and again people tell me they believe he will change their lives.

After all he began his own life in the slums of Monrovia. He understands their struggle, they say.

A look at George Weah's life

I catch up with George Weah again during an official visit to a mosque in the centre of Monrovia.

As he is being swept along the hallway I manage to ask if he can possibly satisfy the expectations of those who were cheering for him outside.

"I know I am going to meet the expectations… when people love you, you have to strive for them.

"So there's a lot of expectation but we will meet the expectation… because this is a whole global world we want to create… where you will come to help our people…" He smiles at me as he says this.

Mr Weah grew up in Monrovia's Gibraltar slum

Critics point out that so far his promises have not been backed up by detailed plans.

In fairness, George Weah would not be the first politician to avoid spelling out how he plans to fund his campaign manifesto.

But few in the world face the pressure of hope that he has ignited among the poor.

Nobody doubts his ability to motivate and inspire. The unknown quantity is his capacity to administer effectively.

He chose the ex-wife of former warlord Charles Taylor, Jewel Howard Taylor, as his deputy.

Having historically been a staunch critic of Taylor and his National Patriotic Party (NPP), questions are being asked of the motives.

As a correspondent returning to a country I previously knew only in war, the contrast is astonishing. The markets are full. The schools are thronged. Fear has been vanquished.

But only prosperity can keep it at bay. With great hope comes, always, the possibility of great disillusionment.

Few leaders anywhere in the world face as daunting a task as that which now confronts George Weah.

- Published22 January 2018

- Published22 January 2018

- Published6 October 2017

- Published13 February 2024