Zimbabwe: Did Robert Mugabe finally go too far?

- Published

President Mugabe's ties to the military date from the liberation struggle

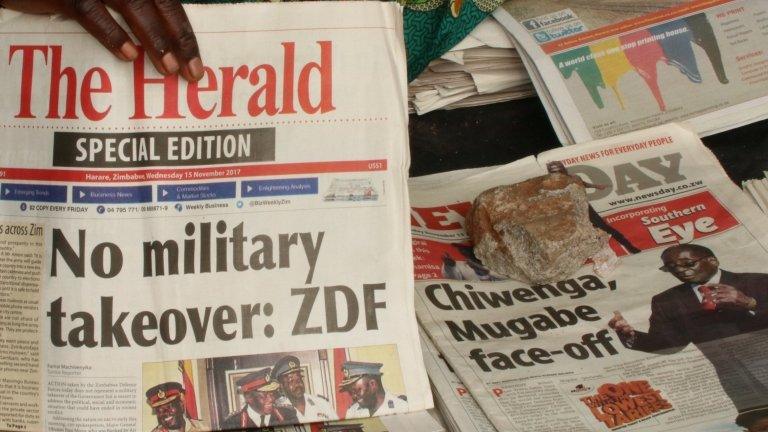

Zimbabwe's military says its actions do not amount to a takeover. It still refers to Robert Mugabe as the commander-in-chief of the country's defence forces. But practically speaking, Mr Mugabe is not in charge if his forces can step in to usurp his authority.

This is not a coup d'état in name, but it appears to be in action.

The military takeover of the national broadcaster, the presence of troops on the streets and major access points, and even forced entry into the presidential palace are traits of a military takeover - at least as we have seen them in Africa.

One thing that is lacking is that the constitution has not been suspended.

The cementing of democracy across Africa has led to a general regional and continent-wide aversion to violent takeovers of government.

Even in the past, coup-stagers often promised a quick handover to civilian government through elections or a negotiated transition.

The military says it has not taken control of the country

So far in Zimbabwe, the military is not showing any intention of assuming a governing role.

However, it has someone it would prefer to do that. Emmerson Mnangagwa, the recently sacked vice-president, is held in high regard in Zimbabwean military circles.

He was involved in the struggle for independence, and in 1980 created the Zimbabwe National Army by fusing the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (Zipra) and Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (Zanla) with the remnants of the former Rhodesian security forces.

He was seen as the natural successor for the top office.

President Mugabe sacked Mr Mnangagwa last week at the prompting of the First Lady Grace Mugabe, who has political aspirations and has publicly opposed the former vice president, but does not have support within a military where the liberation legacy is held in high esteem.

Grace Mugabe is a divisive figure in Zimbabwe

The top military officials were part of the liberation struggle, like their comrade and president Mr Mugabe, so they have supported his government over the years because he has served their interests.

They did not act this way in 2014, when Mr Mugabe sacked his previous Vice President Joice Mujuru, a former independence fighter, in a similar power struggle.

This time though, there is a sense the president might have gone too far.

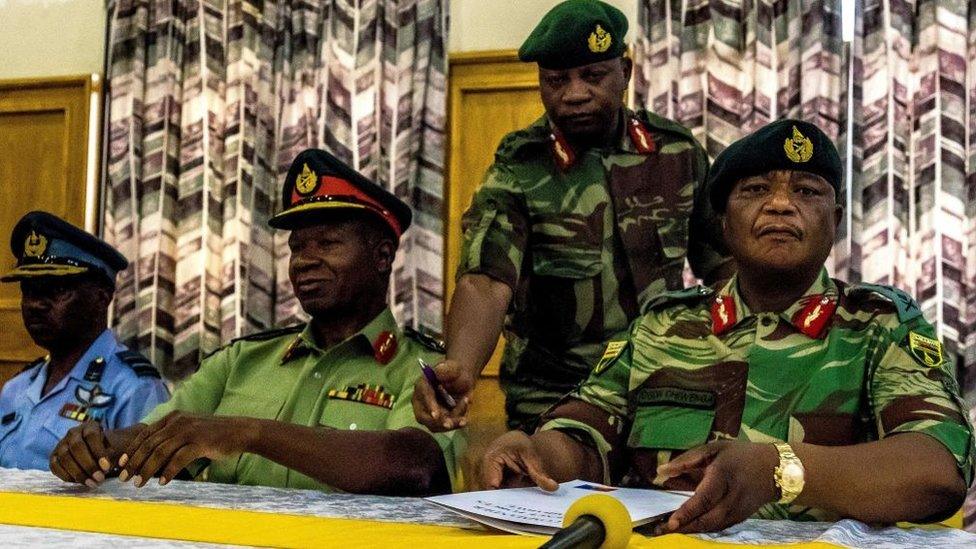

Gen Chiwenga said that the military would not allow the purging of leaders with a liberation background from the governing party

Earlier this week, the commander of Zimbabwe's Defence Forces, General Constantino Chiwenga, warned the Zanu-PF governing party to stop the purge against independence war veterans.

Following his dismissal and escape to South Africa, Mr Mnangagwa promised to return to regain control of the ruling party from the Mugabes.

This suggested his confidence in the support he had from the military.

Emmerson Mnangagwa is highly respected in army circles

So the next step would be to negotiate his return ahead of the party congress in December, where he could be affirmed as the president's successor.

At worst, the military will force Mr Mugabe to resign - but they will not want to humiliate him further because of the history they share.

They will also extend the courtesy to Grace Mugabe, in spite of her recent actions.

Painful memories

Prior suggestions that the armed forces were divided have not been revealed so far this week.

The rise of an opposing faction would probably be bloody, and not something Zimbabweans would like to see, regardless of how tough life has been in recent years.

The end of the Mugabe era would be a relief to many, but Mr Mnangagwa is not necessarily popular in all parts of the country.

Under his tenure as security minister in the early 1980s, government forces crushed a rebellion in the Midlands and Matebeleland province, and allegedly killed thousands of civilians.

There is still bitter resentment among people from the affected regions.

- Published15 November 2017

- Published17 November 2017

- Published15 November 2017

- Published19 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published15 November 2017