Losing hope amid Uganda doctors' strike

- Published

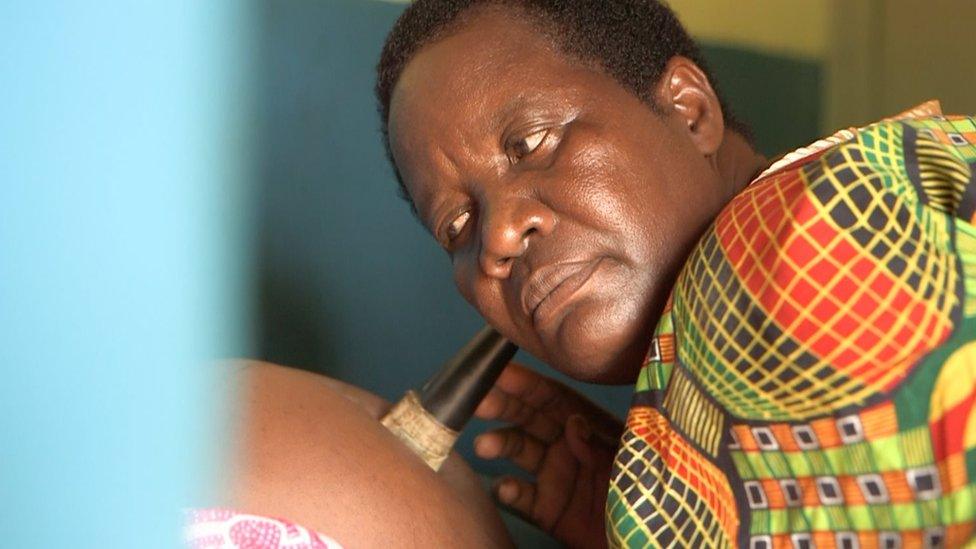

A patient waits to see a traditional healer as the Uganda doctors strike carries on

Uganda's doctors have gone on strike, fed up with what they say are the lowest wages in Africa and a lack of resources. They are demanding that their salaries, currently starting at just $260 a month for junior doctors, increased 10-fold, as well as benefits like cars and domestic workers.

But as the fight between the Uganda Medical Association and the government rumbles on, what does it mean for those Ugandans in desperate need of medical attention? The BBC's Catherine Byaruhanga meets the families caught in the middle.

The crumbling buildings housing Kamuli General Hospital's wards and clinics are almost entirely deserted.

With most of medical personnel not coming to work, patients who would usually attend this hospital in rural eastern Uganda have taken their cue, and nearly all the beds are empty.

But it doesn't mean people don't need care.

Desperation

There is a sudden rush of activity as men carry 60-year-old Sulayi Kasadha into one of the rooms, lifting him by his clothes. He is barely conscious and convulsing. His chest thumps up and down, while his family looks on nervously.

His brother James Tibiryala tells me: "We are almost losing hope, it is really very bad."

Mr Kasadha fell ill two days previously.

Diagnosed with high blood pressure, he was first taken to the local Catholic mission hospital. But they didn't have the drugs or the necessary CT scanner, so instead his family brought him to the public hospital in critical condition.

Even here Dr Charles Waako - the only doctor on call - is struggling to do better.

Dr Charles Waako finds himself unable to help those who do come to hospital

The family has to buy the doctor gloves, as the hospital has run out. He inserts the plastic end of a syringe into Mr Kasadha's mouth to clear his airways. The machine needed to help him breathe is broken.

"It's so depressing," the doctor tells me. "You have such a patient, in a very critical condition, but everything you want to use... We're just improvising. The medicines we want, we're just improvising.

"They're not the appropriate medicines but we think they might work for him."

In the end, it won't be enough. Dr Waako refers Mr Kasadha to a private hospital in the nearest big town which might, hopefully, be better equipped.

For him, the desperation of the situation highlights the need for the industrial action.

"What we want is improved welfare for the medical workers, improved working environment and also the provision of the necessities in the hospitals and health facilities," he said. "This in the end is going to benefit the clients."

Many Ugandans will tell you that, with or without the strike, the country's health system simply does not work. Medical stock-outs - when drugs are simply not available - are common, including for anti-retroviral dugs needed for HIV patients.

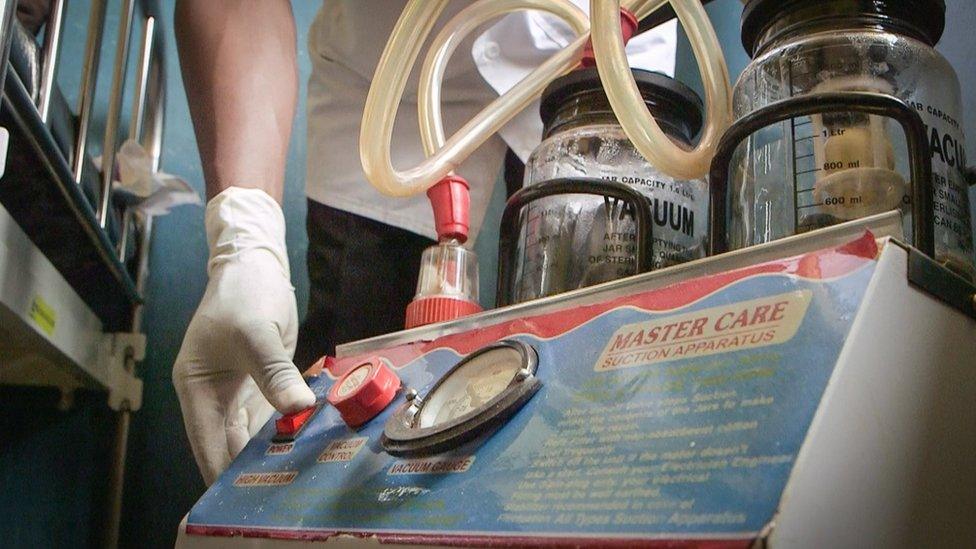

One reason the doctors have gone on strike is the poor equipment they have to treat patients with

Then there is a chronic shortage of doctors. More than 40% of positions are unfilled, according to the Health Ministry, not to mention the absenteeism by health workers who moonlight at private facilities.

Patients with enough money have turned to private hospitals during the strike.

Milly Namusobya cannot afford the cost. Eight months pregnant with her first child, she is experiencing pain in her abdomen.

But Kamuli General Hospital could not help.

"I was shocked to find that there were no doctors or medicine at the government hospital," Ms Namusobya says.

"While we were there, we were advised that there are some elderly ladies who can help us understand our pregnancy, our complications or how our babies are growing in the womb. That is how I ended up coming to this traditional birth attendant."

Milly Namusobya cannot afford the costs of private treatment

In a small clinic by the roadside, Deborah Magada helps Ms Namusobya onto a wooden table before pressing her hands against Ms Namusobya's lower abdomen, and then uses a traditional Pinard horn to listen to the baby's heartbeat.

She is confident of her diagnosis.

"When pregnant women are due to give birth and the head is facing downwards, they feel pain because the head is bigger and doesn't fit in the pelvic area, that's why the pain is there. And while the baby is turning in the womb, it leans on the walls of the womb and moves."

But traditional birth attendants lack the right training and equipment so are discouraged by authorities.

With the strike affecting many across the country, the government's hardline response - threatening to sack those taking part - has been replaced with a special committee aiming to reach a negotiated settlement.

Unfortunately, the official position is that there is not enough money to boost doctors' wages.

The authorities usually tell patients not to use traditional midwives like Deborah Magada

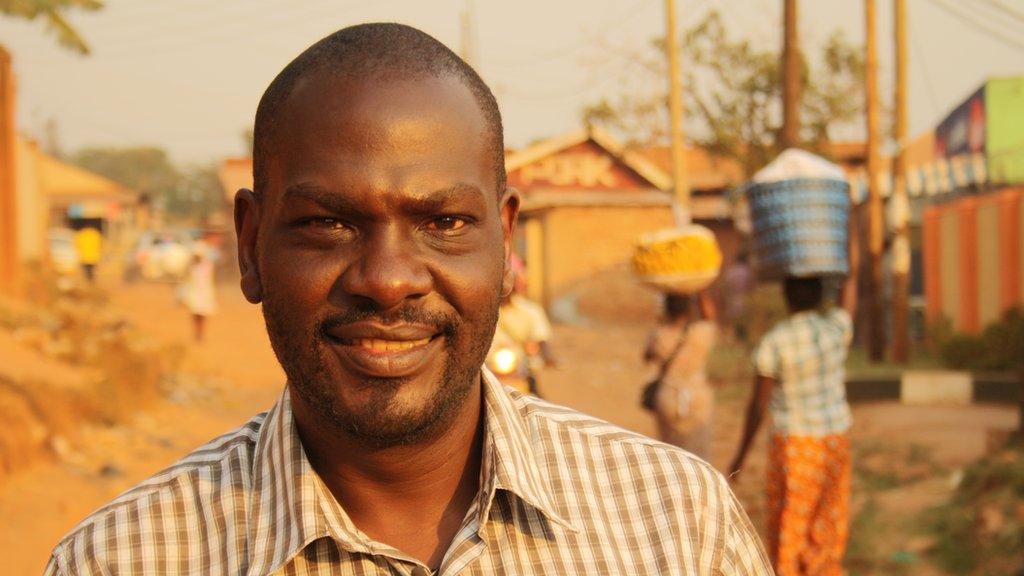

Don Wanyama, the president's spokesman, explained: "We have a very small resource-envelope as a country and with very many competing needs. Because of that, public servants perhaps have not been given the money they really want to get.

"But the president has indicated that [when] the pressure on other investments reduces, there should be some little more money to spend on workers of government."

Some doctors dismiss this argument - particularly after more than 400 MPs were given $8,000 each to look into removing presidential age limits, allowing President Yoweri Museveni to run for a sixth term in 2021.

As for Mr Kasadha, by the time he reached the next big hospital he was in a coma. The only working CT scanner is in an expensive hospital in the capital - two hours away. His struggling family is trying all they can to save him.

Ms Namusobya, meanwhile, is hoping the strike ends before she gives birth.

Otherwise the traditional birth attendant's office without any proper facilities is her only option.

- Published13 August 2017

- Published21 September 2017

- Published21 February 2015

- Published30 October 2014