Robert Mugabe: 'The last political king of Zimbabwe'

- Published

A journalist for 20 years in Zimbabwe before he became a barrister, Brian Hungwe reflects on the occasion when Robert Mugabe snapped back at him after he asked the veteran leader whether he intended to retire.

I begin with a disclaimer. I am not a prophet.

But, several years down the line, there shall be a movie, probably named The Fall of the Last Political King of Zimbabwe.

It will feature a divisive wife, and her husband, a tyrant, hoist by their own petard. And, maybe, an Oscar will follow.

At Zimbabwe's State House in 2013, I asked then-President Robert Mugabe, who was 89 at the time, whether he would run for another four-year term at the age of 94.

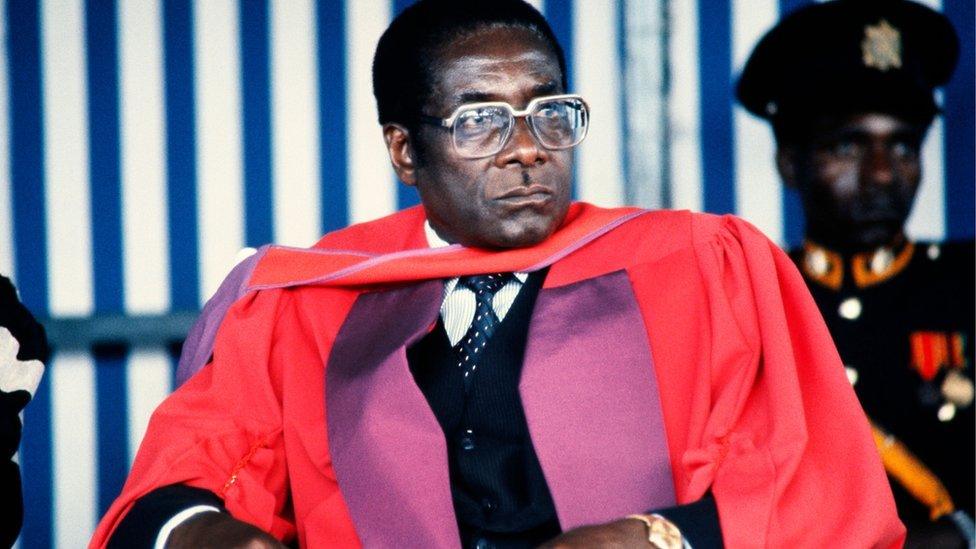

Robert Mugabe had an aura of invincibility

I posed the question innocently, thinking it would be quite something for a nonagenarian to seek re-election.

Mr Mugabe was not amused.

"Why? Would you want to wish me dead?" he asked.

I replied to Mr President that I had no such wish but was just wondering about his plans.

He said that it was for the people to decide, not him. I think in that answer I detected a man who was determined to keep a tight grip on power under any, and all, circumstances.

Grace Mugabe harboured ambitions to become president

Ministers did confirm to me that he occasionally dozed off during cabinet meetings, was too frail to walk, and sometimes exhibited memory lapses.

Despite this, Mr Mugabe had no intention of retiring. Indeed, his wife, Grace Mugabe, told a public rally that her husband would rule Zimbabwe from a wheelchair and even from the grave.

"One day when God decides that Mugabe dies, we will have his corpse appear as a candidate on the ballot paper," the ex-first lady said. in February.

"You will see people voting for Mugabe as a corpse. I am seriously telling you - just to show people how people love their president," she added.

'Sheer eloquence'

I have no doubt that from Mr Mugabe's perspective, his 37-year reign ended because of the outright betrayal, hypocrisy, deceit and the treachery of his long-time comrades in the ruling Zanu-PF party.

And yet it was he who betrayed them to pave his wife's path to power.

This included his deputy, Emmerson Mnangagwa, a loyal party cadre he knew from the war for independence in the 1960s and 1970s, and the army chief, Gen Constantino Chiwenga, whom he wanted arrested and charged with treason after arriving from an official trip to China earlier this month. Events escalated after this.

Mugabe: From war hero to resignation

I attended a good number of Mr Mugabe's political rallies in my 20-year career as a journalist.

He had an aura of invincibility and his speeches, which were full of rhetoric, were delivered with sheer eloquence. Many liked, revered, and respected him. But he was also hated in equal measure.

The events that were to destroy his political career began in 2014, when his wife started addressing rallies. She went on to attack Mr Mnangagwa, accusing him of fanning factionalism and working against her husband.

She further attacked the army for meddling in party politics after it raised concern about the growing influence of the Zanu-PF's G40 faction, made up of Young Turks who were backing her presidential bid.

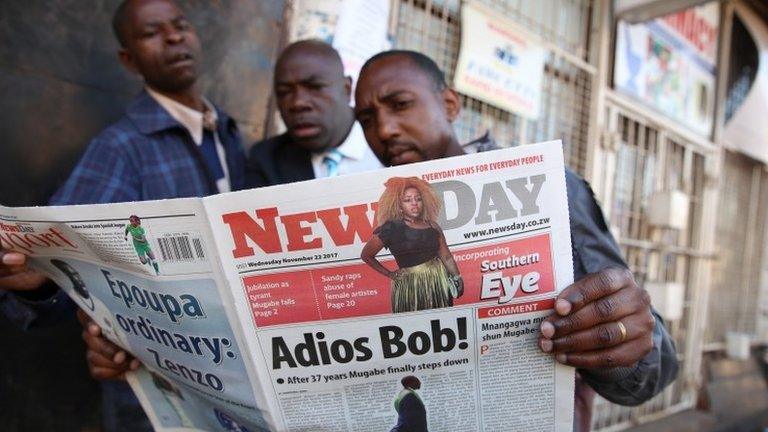

Zimbabweans have been celebrating the end of Mr Mugabe's rule

This raised anxiety and tension and Mr Mugabe, rather than playing a unifying role, chose to side with his wife. The army felt betrayed, as it became apparent that their commander-in-chief no longer had much trust in them.

Things were clearly getting out of hand. The biggest clue came when war veterans, backed by the army, held a press conference in July 2016, asking Mr Mugabe to step down. They accused him of dictatorial tendencies, egocentrism and misrule.

Mr Mugabe was angry, but took no action to address their concerns. The writing was on the wall.

'Political scalp'

An African proverb says: "If a leopard want to eats its own, it accuses them of smelling like a goat".

Attacks on Mr Mnangagwa intensified, and he was accused of focusing more on fulfilling his presidential ambitions than working to improve the struggling economy.

Most Zimbabweans have only known Robert Mugabe as president

He offered to resign three times, but Mr Mugabe rejected it each time. Then on 8 November, Mr Mugabe took Mr Mnangagwa's scalp, or so he thought, by firing him as vice-president.

Mr Mugabe knew that the purge to clear the way for his wife would not be complete without arresting the army chief.

His loyalists tried to detain Gen Chiwenga, soon after he returned from a trip in China, but they failed after the army became aware of the plan.

The general then moved against the frail Mr Mugabe, putting him under house arrest and launching an operation to target "criminals" around him.

After holding out for more than a week, Mr Mugabe resigned. His fate was sealed by the liberation war comrades he had chosen to betray.

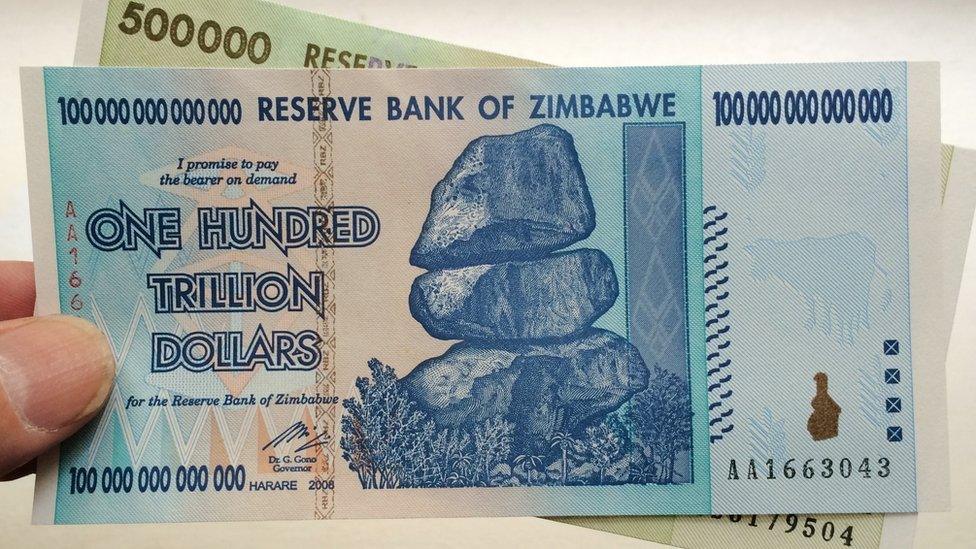

The question that arises now is whether Mr Mnangagwa will scrap the ruinous policies that turned Zimbabwe into a basket case.

Can he rebuild the economy, and create, as he promised, "jobs, jobs jobs"?

Let's wait and see. As for Mr Mugabe, he is history.

Read more:

How news of Robert Mugabe's resignation was greeted across Zimbabwe

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published20 November 2017

- Published17 November 2017

- Published16 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published3 August 2018

- Published25 July 2018

- Published21 November 2017