Crossing Divides: Kenya jail's 'mindful' scheme aims to bring sides closer

- Published

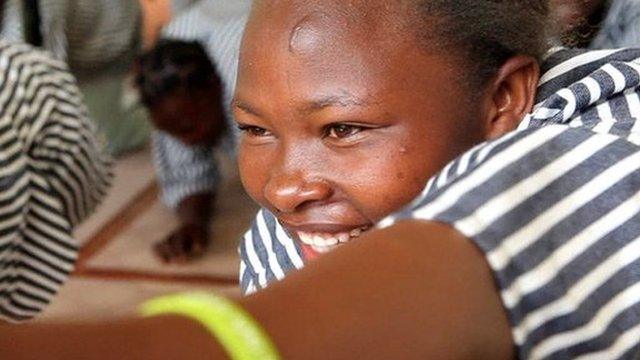

Inmates say they now refer to warders as "teachers"

Kenya's prisons are hotbeds of violence. But could an experiment with mindfulness bring inmates closer to their hated guards, asks BBC Africa's Mercy Juma.

The prison gate stands some 2.4m (8ft) high, a black mass of steel bars, topped by sharp, shiny razor wire.

This is Naivasha GK Prison, Kenya's largest maximum-security jail just north of Nairobi, where more than 2,000 men are serving life sentences or awaiting the death penalty.

In a dimly lit hall, dozens of men in navy-striped uniforms sit in neat circles with a handful of green-clad warders.

They are silent. You can hear yourself breathe.

"Take a deep breath; in... out... close your eyes," says a guard in the centre. "Notice your posture. Sit upright. Are you relaxed, your shoulders down, your face soft?"

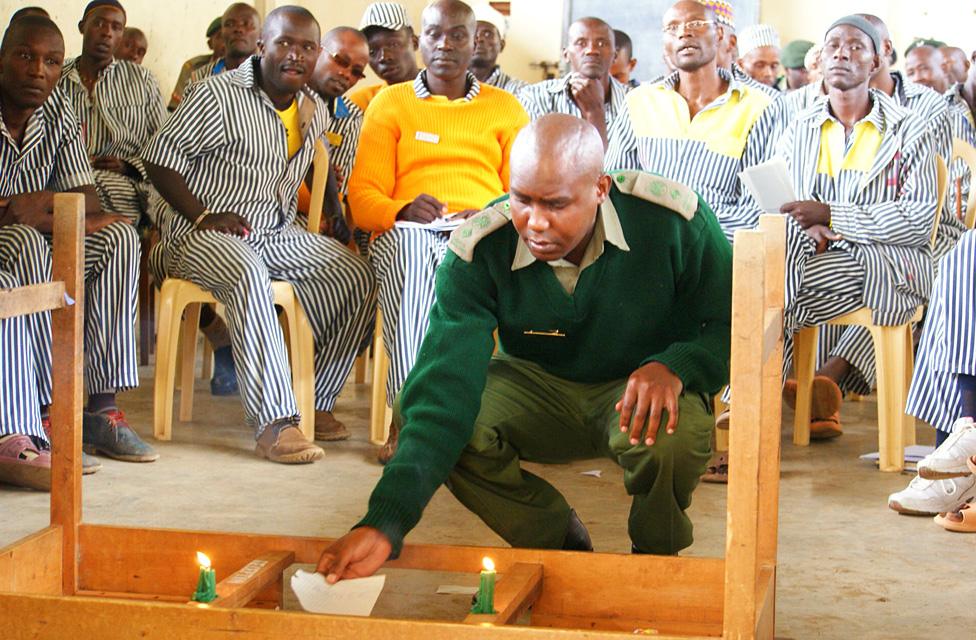

Prisoners watch a guard burning a piece of paper with negative emotions written on it

Everyone has their eyes closed, barring the odd few with far-off gazes; cloudy eyes here, a squint there, but no blink. They are in deep concentration.

"Take note of your breathing. Focus on this moment," the guard continues. "Your thoughts will wander. It is okay. Just appreciate what is going on in your mind, but come back and focus on your breathing. Breathe in... out."

Seeing guards 'as brothers'

This peaceful scene - so at odds with the harsh environment - is a session from the prison's mindfulness training programme.

Mindfulness - focusing on the present while calmly accepting your feelings, thoughts and sensations - is said to change the way people deal with their experiences. Its proponents say it can reduce stress and anxiety, help people let go of what cannot be changed and better manage their emotions.

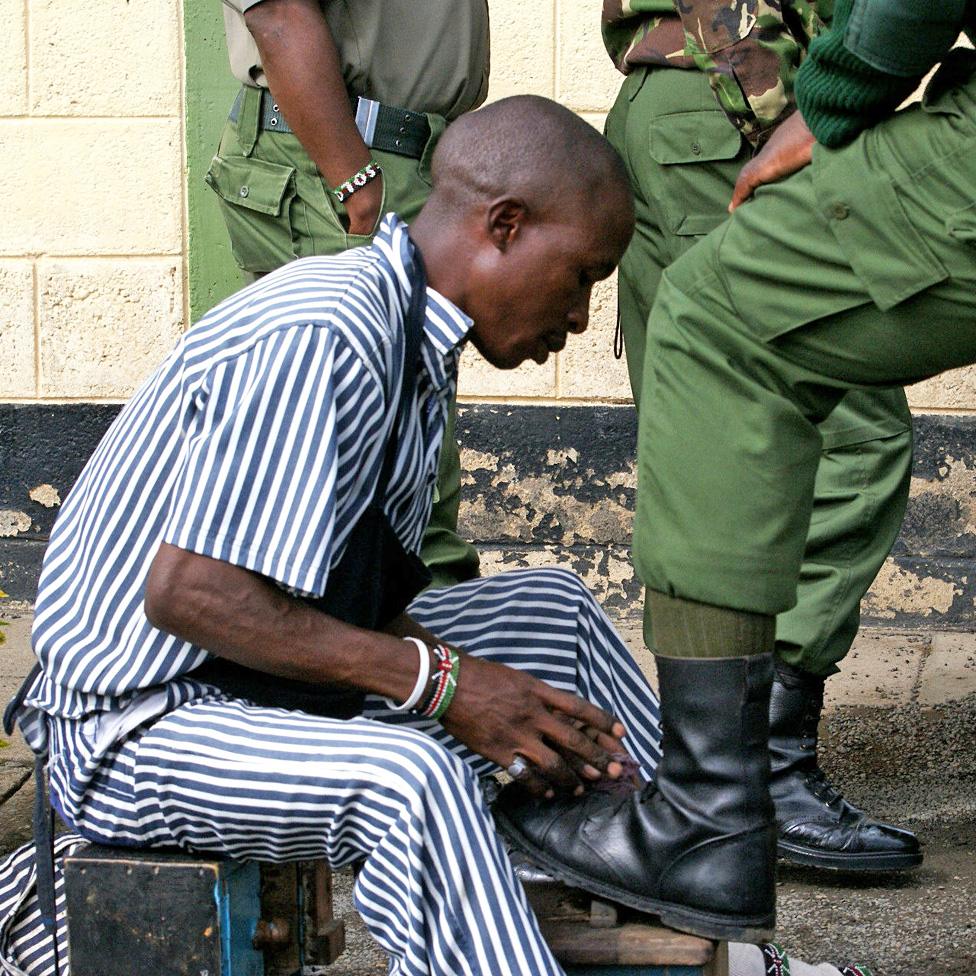

Many inmates hate guards as symbols of the authorities that sentenced them. Kenya has seen numerous cases of prisoners ganging up against warders, and guards torturing convicts.

An inmate polishes a guard's boots

This facility's mindfulness programme was devised to bring them together.

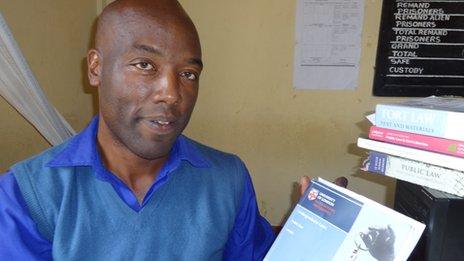

"Between me and them it was like hell and heaven. There was nowhere we could meet. We could not see eye-to-eye. I saw them as killers," says Willis Opondo, an inmate serving a life sentence for violent robbery.

"When someone died in my cell, I stayed with the body for almost three days without saying because I knew the kind of beating I would receive, even though I didn't kill him," he says, with a faraway look.

The mindfulness sessions have offered him a kind of sanctuary. He is learning to let go of his fears, negative emotions and pain, and says he is a different man from the one brought in 18 years ago.

"Today, I see the guards as my brothers, my keepers. We can talk, we can chat, we can laugh. They can give me hope. We no longer call them afande (sir), we refer to them as our teachers," he says, smiling at the warder seated next to him.

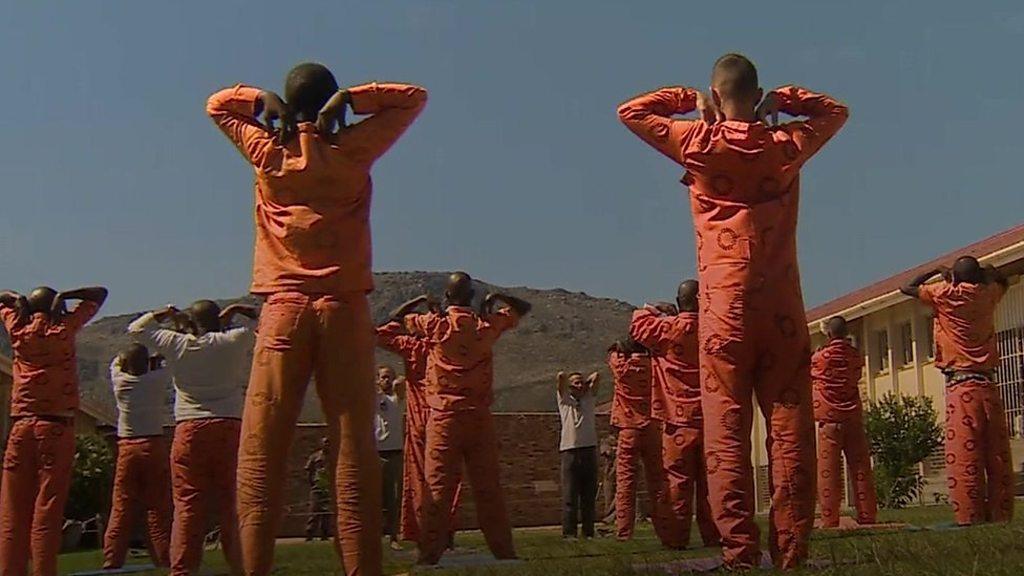

Kenyan prisons remain overcrowded

The atmosphere of despair, tension and aggression in many prisons leaves warders susceptible to mental health issues like post-traumatic stress disorder.

The African Prisons Project reported that in 2016 many prisons in Africa were operating at 300% of capacity,, external with about 80% of inmates lacking basic access to justice.

Many Kenyan prisons were built in colonial times, and some lack rehabilitation facilities.

'He brought my family to me'

Kevin Onyango, a guard at Naivasha GK, says that for many years he could not control his emotions. The mindfulness training encouraged prisoners and warders to expose their vulnerabilities, sharing even the most intimate information.

"Over time I have learnt how to be composed, to keep my emotions in check," he says. "I have learnt that these people are human beings first, as much as they are prisoners."

Willis says he arrived in prison when his girlfriend was pregnant and that he had no idea whether she had delivered safely, and whether he was father to a boy or girl. No relatives ever visited.

For many years he kept his troubles private - until one day, after a session, he approached a warder he felt had become a friend.

"I talked to him and gave him directions to my place. He was the first one to bring my family to me. He made it possible for me to see my daughter for the first time," he says, grinning.

But reflection and self-awareness rarely comes easily. Many participants took a lot of convincing to take part.

"It felt funny and stupid," one says. "I found it weird. How do you just breathe in and out and sit quietly for 10 minutes?"

"Initially I could not focus. I was frustrated. I was very negative," says another.

Song, poetry and art

Over time things changed. A survey of prisoners published in February 2017 suggested the training had helped inmates develop stronger bonds with each other, and improve relationships with families outside.

Of the 140 inmates surveyed, 80%-90% reported feeling less stressed and angry. Many felt more forgiving, saying they were embroiled in less conflict and aggression, and used drugs and alcohol less.

Matthew Mutisya, the assistant commissioner in charge of Naivasha, says the prison has become easier to manage.

"We have fewer riots and attempted escapes. I can walk inside the prison without being armed. Many of them are less aggressive," he says.

But Mr Mutisya admits many do not take part in the sessions.

"We ask them to try for even one week and if they feel it is not beneficial, they are free to drop it. But very few of those who agree to do the training leave midway," he adds.

Dr Inmaculada Adarves-Yorno, a lecturer in leadership studies at the University of Exeter, pioneered the Naivasha programme. She says acceptance is one of the most important and difficult challenges.

"Accepting one's circumstances is not the same as not wanting change. Individuals can still work towards change even as they settle into an acceptance of who and where they are," she writes at the Conversation, external website.

Throughout the session the teachings are transmitted in different ways including through song, poetry, art and mindful affirmations.

On the floor in the middle of their circle, three candles flicker.

One by one the participants write down the emotion they would like to release, then come forward to light their papers and throw them in a metal bowl. Words like anger, sadness and revenge go up in flames.

Each admits that every day is a struggle. But as time goes by, they hope to create meaningful relationships beyond the colour of their uniforms. Some of the inmates may never leave prison but at least, they say, their minds are free.

Crossing Divides

Crossing Divides: a week of stories about people creating connections in a polarised world.

How to survive a difficult conversation

- Published15 January 2017

- Published24 February 2017

- Published15 August 2014

- Published21 May 2013