South Africa's school pit latrine scandal: Why children are drowning

- Published

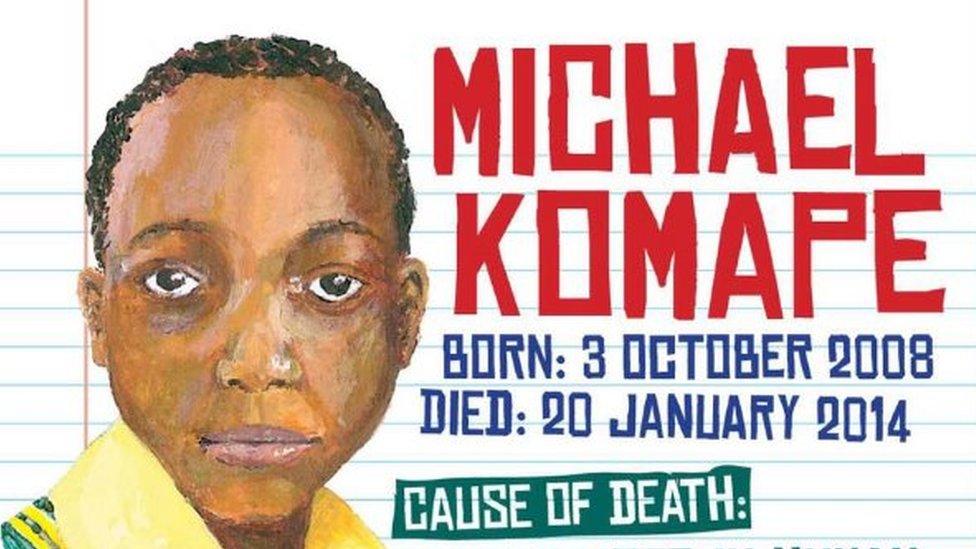

During his first week at school, five-year-old Michael Komape drowned in a pit latrine in northern South Africa.

That day in January 2014 will be one his father James Komape will never forget.

As he takes me back to the school in Chebeng village, where the tragedy struck, his pain is palpable.

"When I arrived at the opening of the toilet hole all I could see was a small hand," he says.

"Some people were standing looking into the hole, no-one had thought to take him out. It's the saddest thing I've ever seen.

"No-one should die like that."

He pauses for a moment before continuing.

"He must have been trying to call for help to maybe even climb out. It's hard to accept that my son died alone and probably afraid."

Michael Komape's parents plan to appeal against a recent ruling which denied their claim for damages

Mr Komape struggles to make eye contact.

Instead he fixes his eyes on the neat row of brick toilet stalls, which were built after his son died in the toilet of rusty corrugated iron just metres away.

The iron sheet that had served as the seat collapsed when Michael sat on it. He fell in, along with the seat and its white plastic lid, the authorities said.

But this is not a one-off problem affecting one school.

While access to proper sanitation is a basic human right enshrined in South Africa's constitution, many pupils have no choice but to use pit toilets.

South Africa's school pit latrines

More than 4,500 schools have pit latrine toilets, out of almost 25,000 nationwide

Many are made from cheap metal, are shoddily built and left uncovered

Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo provinces are among the worst, says Education Minister Angie Motshekga

Eastern Cape has 61 schools with no toilets at all, and 1,585 schools with pit latrines

Neighbouring KwaZulu-Natal province has 1,379 pit latrines in use

Limpopo province, where Michael Komape went to school, has at least 932 unsafe toilets

How did things get so bad?

Analysts say it is partly a legacy of apartheid, since under white-minority rule virtually no resources were allocated to develop schools for poor, predominately black children.

Also to blame is the failure to maintain existing infrastructure, however basic.

Michal Komape died in this pit latrine at Mahlodumela Lower Primary School

Back at their home just outside Polokwane, the main city in Limpopo province, the Komapes tell me they want justice for Michael's death.

With the help of Section27, a human rights law firm, the family are set to appeal against a recent court ruling which rejected their claim for damages over the incident.

The suit is against Limpopo province's education department, which the family believes was negligent.

Section27 is helping the Komapes to take the case to court

"The Komape case is a tragic one but it is an illustration of the dire state of public school facilities in the country," Section27's Zukiswa Pikoli told the BBC.

"We were quite shocked when we heard about the tragedy. There was no way we were not going to help."

Ms Pikoli says Section27 is planning to take the case to the Constitutional Court, South Africa's highest court.

Pupils at a school close to where Michael Komape died must now accompany each other to the toilet as a new safety measure

The Komapes are not the only family to lose a child in this manner.

Earlier this year in the rural province of the Eastern Cape, a five-year-old girl drowned in a pit latrine.

Lumka Mkhethwa went missing without a trace from Luna Primary School in March.

The village was notified and a manhunt was conducted overnight by the community, but she could not be found.

The following day the police returned to the school where she had last been seen.

A pack of sniffer dogs lead them to the grisly find. Her tiny body was at the bottom of a dark, faeces-filled toilet.

After her death, South Africa's new President Cyril Ramaphosa called for pit latrines in schools to be eradicated and gave the education department three months to come up with a plan.

But this will need money.

'Years of neglect'

An interim government report suggests it will cost more than 11bn rand ($876m; £660m) - a sum it hopes to raise with help from the private sector.

"We are having to address many years of neglect and but change is coming, even if slowly," says Elijah Mhlanga, an official in the lower education ministry.

Michael Komape's death has galvanised the community where he lived

"These two incidents have been tragic but we are hoping that this shows everyone the seriousness of the crisis," he adds.

"We have received interest, with people offering to help with the funding.

"It is our intention to see that all the children in our schools are in safe facilities."

Teacher patrols

In another village in Limpopo province, word of Michael's death has changed the normal school routine.

Sebushi Primary School is modest, but clean and well-kept.

Behind a vegetable garden sits a row of pit latrines.

Many have a large opening at the back, where teachers now monitor pupils as they use them.

"Every morning from 06:00 a teacher patrols the toilets, monitoring who goes in and out," says Joseph Mashishi, chairman of this school's governing body.

These brick-housed toilets were built at Michael's former school after his death

"We don't want what happened to the Komape family to happen in our school. No child should have to die in faeces, it is inhumane."

Many in Michael's community have now been stirred into action.

They are fighting to have new toilets installed in all the region's schools, in memory of the young boy whose life ended too early.

- Published29 January 2016

- Published9 July 2024