Zimbabwe election: Can post-Mugabe vote heal divisions?

- Published

Rival party supporters in Harare

Zimbabweans are going to the polls on Monday in the first vote since Robert Mugabe was ousted in November, but BBC Africa editor Fergal Keane says the legacy of his 37-year rule cannot be overlooked.

They simply cannot imagine defeat.

Crowds of Zanu-PF supporters streamed into the national stadium in the capital, Harare, on Saturday morning and every person I spoke to had the same conviction: Emmerson Mnangagwa, who succeeded Mr Mugabe as president, was going to win. And win big.

"It's gonna be an absolutely resounding victory for Emmerson Mnangagwa," said Stanley Bote, a young businessman from Harare.

"You have to consider all he has achieved since coming into office."

There has been a party atmosphere among ruling party supporters

Many others simply laughed when I suggested the possibility of an opposition victory.

Inside the stadium bands played, rappers rapped. The party went on.

Zanu-PF has massive financial resources, control of the state media and immense powers of patronage.

In the nearly 40 years since independence, winning by fair means or foul is a Zanu-PF tradition.

At the heart of President Mnangagwa's campaign lies an implicit confidence that Zimbabweans will be willing to forget, if not forgive, his own and his party's appalling record of misrule and human rights abuses.

Emmerson Mnangagwa, Zanu-PF

Known as "the crocodile" because of his political shrewdness - his party faction is known as "Lacoste"

Accused of masterminding attacks on opposition supporters after 2008 election

Thought to be 75 years old, he promises to deliver jobs and is seen as open to economic reforms

Survived several alleged assassination attempts, blamed on supporters of ex-President Mugabe

His party's campaign literature and rhetoric stresses the imperatives of the present: investment, jobs, education and health care.

In fact all of the things that were steadily ruined in decades of Zanu-PF rule.

But Mr Mnangagwa believes the people should be grateful because he and his co-conspirators in the army rid the country of Robert Mugabe last November.

In June Emmerson Mnangagwa told Fergal Keane he was as "soft as wool"

The mantra "Zimbabwe is open for business" is repeated ceaselessly as the ruling party presents itself as the guarantor of investor-friendly stability.

Ever since the military intervention of last November the new president has been at pains to avoid apologising for the abuses of the past because, as he claimed to me recently, he was "always for peace".

I asked if he would show humility and acknowledge his own responsibility.

He refused, insisting to me that he had never been ruthless but was "as soft as wool".

This is the essential fiction for a man trying to persuade the international community and his own people that he represents a different Zanu-PF to the one they knew and feared.

Yet Mr Mnangagwa was as close as it was possible to be to decisions that inflicted terror and misery.

'We want an apology'

In recent days I travelled to Matabeleland in the south of the country to meet survivors of the massacres of the early 1980s when soldiers of the North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade carried out a campaign of torture and killing.

Attacks by dissidents opposed to Mr Mugabe opened the way for waves of terror directed against the perceived political enemies of the government.

This category was expanded beyond the dissidents to include thousands of members of the Matabele people from the same ethnic group as Mr Mugabe's opponent at the time, Joshua Nkomo.

Sinikiwe Ncube's father disappeared when she was 12 years old

Mr Mnangagwa was then state security minister. His close ally, Perence Shiri - the current agriculture minister - is remembered in Matabeleland as commander of the Fifth Brigade with the nickname of "Black Jesus" because he could decide who lived and who died.

Sinikiwe Ncube was 12 years old when two strangers appeared at the door of her family home near Balagwe village.

"They asked my father to come with them and we never saw him again."

Her father, Samson Ncube, was a teacher and may have been targeted because he was an educated man, the kind of figure whose words were trusted by locals.

I asked Ms Ncube if she was willing to forgive those responsible for his disappearance.

"How can we forgive when the perpetrators have not acknowledged what they did, when they have not apologised. Let them come and say sorry and then we can forgive," she said.

Campaigner Dumisane Mpofu, of the human rights group Freedom First, told me that the memory of past atrocities would prompt voters to reject President Mnangagwa.

"Definitely... it is a given," he said.

"It is likely to influence people to think differently, knowing they might bring into power a political party able to build sustainable peace for their future."

More on post-Mugabe Zimbabwe:

But in several encounters I found wariness.

"I have nothing to say," a young shopkeeper responded when I asked how she felt about the election.

I tried to take a sample of opinion on the dust-blown main street of Maphisa, a small town near the notorious Antelope Mine where bodies were dumped in the 1980s.

A group of men was waiting outside a cafe, hoping to pick up casual labour. But they were unwilling to speak.

Two women on their way to an opposition rally shook their heads and walked away when I asked for their views.

On the wall of a hut in Bhalagwe village, I noticed a flag bearing the face of President Mnangagwa.

"So you're a Zanu-PF supporter?" I asked the woman living there.

"Not at all," she replied, "that's just my shield in case they come calling."

Why Zimbabwe's election is historic

The experience of the Matabeleland massacres is confined to an older generation in a distinct geographical area.

But more recent excesses linger in the minds of voters across Zimbabwe.

The crackdowns that followed the election of 2008 saw murders and beatings.

According to Human Rights Watch up to 200 people were killed, more than 5,000 suffered violent abuse and more than 30,000 were displaced.

This time around there has been nothing like that violence.

But there are persistent complaints of intimidation, the politics of quiet but persistent threat in small villages.

There are hundreds of international observers deployed for these elections but can they hope to uncover what happens when a traditional leader or ruling party official warns villagers in remote places?

The idea that the ruling party saw and heard everything was carefully fostered in past polls.

Election in numbers

23 candidates on the presidential ballot

55 parties contesting the parliamentary vote

5,635,706 people have re-registered to a new voters' roll; the opposition still has doubts about its accuracy

43.5% of registered voters are under 35

10,985 polling stations

16 years since EU and US observers were allowed to monitor elections

This election is a test not only of political support but of individual freedom.

The opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) has accused the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec) - the body which oversees the poll - of bias and arrogance.

It has complained repeatedly about irregularities in the voters roll and the security of ballot papers.

At one point in the past few days the MDC actively debated boycotting the poll.

Zimbabwe election: What do young people want?

But anger over past violence and allegations of current intimidation may play to the advantage of the opposition.

An opinion poll last week saw the MDC close the gap with Zanu-PF from 11 percentage points to three, with 20% of voters undecided.

It is only the second of two opinion polls, so some degree of circumspection is advised.

The final MDC rally of the campaign in Harare drew a crowd of many thousands.

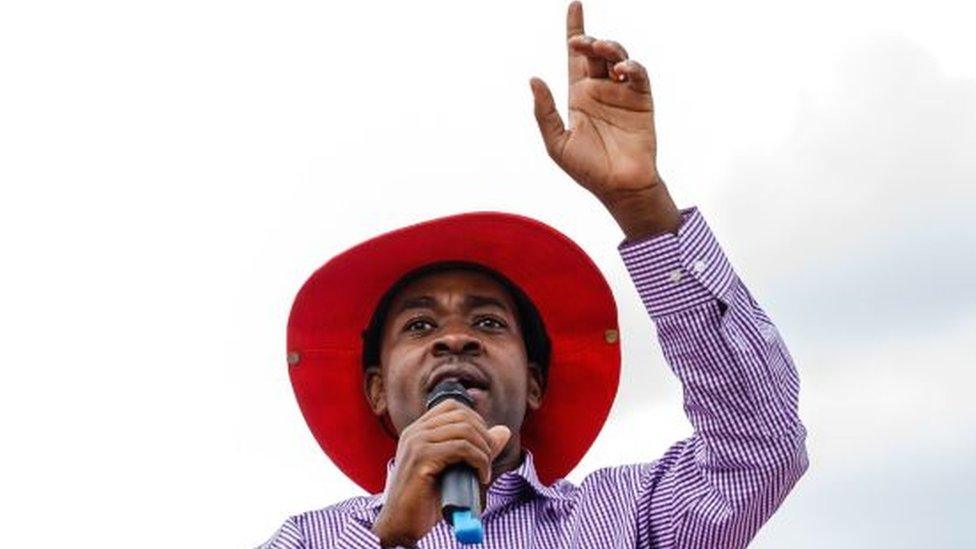

Under its new leader, Nelson Chamisa, a lawyer and pastor, the party's rallies have taken on the fervour of a revivalist campaign.

Nelson Chamisa, MDC Alliance

His skull was fractured when beaten up by state security agents in 2007

Became an MP at 25, a cabinet minister at 31 and could be the youngest president at 40

A recently qualified pastor, he has been using the hashtag #GodIsInIt for his campaign

Witty and humorous orator - his rallies and news conferences are accompanied by much laughter

He has been criticised for making extravagant promises - the introduction of a high-speed bullet train, bringing the Olympics to Zimbabwe - but younger Zimbabweans in particular relish his energy and optimism.

More than 40% of registered voters are under the age of 35.

A generation that has lived with relentless economic decline and corruption under Zanu-PF may be willing to overlook Mr Chamisa's more outlandish statements in return for the precious offering of hope.

Audrey Garakara is desperate for a job and is confident of an MDC victory

At the rally I met Audrey Garakara, a media studies graduate who has been unemployed since leaving college in 2014.

She told me economic desperation made her campaign for an MDC victory.

"This is our year. We will have a free Zimbabwe. Free from corruption. We are winning this election."

On both sides there is confidence.

Past experience would suggest that the power of the Zanu-PF machine and the promise of stability will see Mr Mnangagwa legitimise his presidency.

But Mr Chamisa has run a strong campaign - energetically crossing the country, refining his message to focus on more possible economic ambitions.

He was just two years old when Mr Mnangagwa joined Mr Mugabe in the first post-independence cabinet in 1980.

On Monday the two will fight for the future of Zimbabwe in an election whose outcome is tantalisingly hard to predict.

- Published26 July 2018

- Published23 July 2018

- Published3 August 2018

- Published3 August 2018

- Published28 July 2018

- Published24 July 2018

- Published25 July 2018

- Published26 July 2018

- Published21 June 2018