Ethiopia-Eritrea border boom as peace takes hold

- Published

People come to Adigrat to stock up on all sorts of items

The reopening of the border between former enemies Ethiopia and Eritrea has dramatically changed the towns near the frontier, writes the BBC's Emmanuel Igunza.

The sun had just risen but the market in Adigrat was already coming alive when I went to visit.

Dozens of makeshift stalls lined the street where a group of women traders were sifting chickpeas.

In another place an elderly man was removing chickens from cages and placing them outside his shop.

You can buy almost anything at the market: spices, building materials, fridges and washing machines.

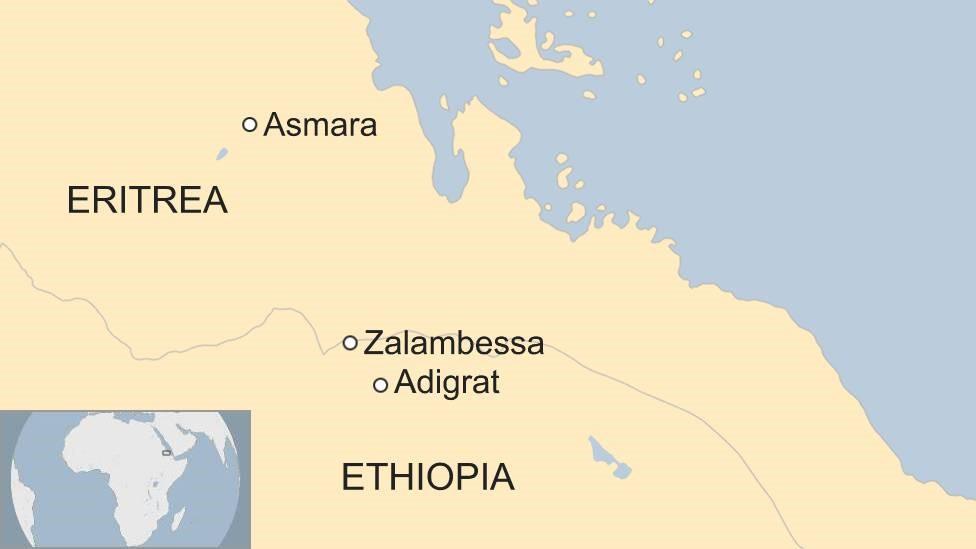

The market in this Ethiopian town, just 38km (24 miles) south of the border, has been transformed since the border opened four months ago after a peace deal ended the "state of war" between the two nations.

Many Eritreans now cross over to see what they can buy.

'We love peace'

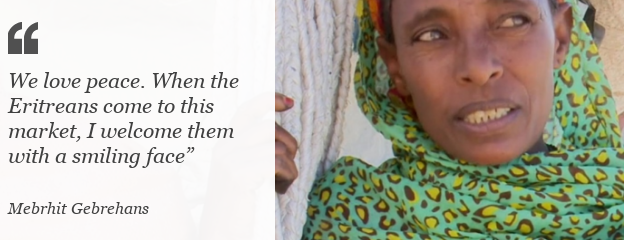

Mebrhit Gebrehans, a middle-aged woman with a big smile, is one of the traders whose business is booming.

She was busy opening a sack full of fresh spices and was calling over potential customers when I met her.

"What we fear is war. We love peace. When the Eritreans come to this market, I welcome them with a smiling face. They buy spices, honey, grains and even biscuits. And we buy different clothes from them," she said.

"When the border reopened, we were worried there would be shortages of some things, but there hasn't been. Everything is normal," she added.

Just down the road, there was a section of shops selling plastic wares, from brightly coloured water tanks to jerry cans to plastic sandals.

The Ethiopia-Eritrea war destroyed a lot of infrastructure close to the border

Shop owner Haile Bisrat told me cheerfully that treating his Eritrean brothers well was not only about cementing peace. It also made good financial sense.

"We get to make a little more profit than before as the market is in a better state.

"When the border first reopened, as many as 2,000 Eritreans were coming every week. The numbers have gone down a little, but that's perhaps because they've bought everything they wanted."

Adigrat was full of cars and lorries with Eritrean registration numbers.

Many of the lorries we saw were carrying building materials like cement and construction cables. But small cars were also carrying huge loads of goods like mattresses, cereals and washing machines.

At the local bus station, touts were shouting the name of the Eritrean capital, Asmara, hoping to draw in Eritrean customers.

Beyene Tewelde was one of them. He had travelled hundreds of kilometres to shop here.

"I came to buy what I need. So I've got shoes, containers and spices.

"The prices are very fair. Before the reopening of the border, I used to buy everything in Asmara. But from where I live, Adi Qeyih, it's better to come to Adigrat than Asmara."

Adigrat is easier to get to than Asmara for some Eritreans

The reopening of some of the border crossings, including one earlier this week, is part of the peace deal signed last July by Eritrea's President Isaias Afwerki and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

The agreement has also seen diplomatic ties renewed and phone links between the two countries restored after being cut off for nearly two decades.

The war, fought over the exact location of the common border, began in May 1998 and left tens of thousands of people dead.

You may also like:

It ended in 2000 with the signing of the Algiers agreement.

But peace was never fully restored as previous Ethiopian administrations under the late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi and his successor Hailemariam Desalegn refused to fully implement a ruling by a border commission established in terms the agreement.

Relatives and friends have reunited since the restoration of diplomatic relations

But last July, Prime Minister Abiy and President Isaias agreed to end the conflict and usher in what they called a "new era of peace" that has seen relations between the two countries and other neighbouring states thrive.

Zalambessa, just south of the border, was on the frontline and badly hit by the conflict.

Rebuilding homes

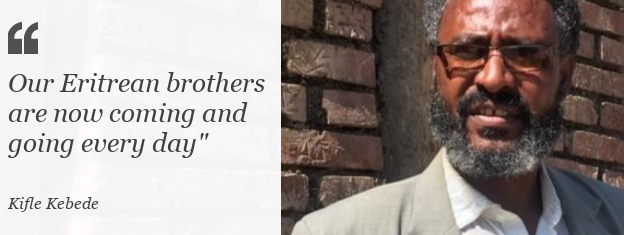

"Everything in this town was ruined," 50-year-old Kifle Kebede told me as he stared into the dusty field in front of him.

Even now, the signs of the damage are visible. Collapsed and abandoned buildings dot the small town. Some bear the signs of being shelled while others have bullet holes on their walls.

"It wouldn't be a lie if I told you that Zalambessa really looked like a field with just piles of stones. All you could see were rocks and dirt," Mr Kifle added

But life seems to be returning to normal following last month's withdrawal of troops from disputed territories.

Families like Mr Kifle's, which had fled the conflict, have started to return to their homes.

When I met him, he was busy supervising the finishing touches in his project to rebuild his family home, which was destroyed at the height of the conflict.

He sensed a perfect business opportunity.

"Zalambessa is the last town before Eritrea and our Eritrean brothers are now coming and going every day. We might do our own business from the house or rent it out.

"Before, renovating a house in a town where not a single vehicle spent the night just wasn't worth it. Now is the time," Mr Kifle said enthusiastically.

There is a hope that factories like this one in Zalambessa can be rebuilt

Before last September, it was impossible to use the road linking Eritrea and Ethiopia that went through Zalambessa as it was completely closed off.

Huge boulders were across the road blocking access to the border area, but now lots of Eritrean cars are passing through.

There has been a dampener in recent weeks with moves that have brought confusion and uncertainty over the future of the open border crossings.

In a surprise decision, officials said those passing through the border should have prior authorisation from their respective countries.

Neither Ethiopia nor Eritrea have given a clear indication why the control measures were put in place but they are unlikely to snuff out the sense of optimism in the border towns.

- Published3 January 2019

- Published11 September 2018

- Published13 December 2018