Rwanda genocide: Nation marks 25 years since mass slaughter

- Published

Rwanda genocide anniversary: The country will mourn for 100 days

Rwanda's president said the country had become "a family once again", while marking the 25th anniversary of the genocide that killed 800,000 people.

Paul Kagame, who led a rebel force that ended the slaughter, lit a remembrance flame in the capital Kigali.

Rwandans will mourn for 100 days, the time it took in 1994 for about a tenth of the country to be massacred.

Most of those who died were minority Tutsis and moderate Hutus, killed by ethnic Hutu extremists.

"In 1994, there was no hope, only darkness," Mr Kagame told a crowd gathered at the Kigali Genocide Memorial, where more than 250,000 victims are thought to be buried.

"Today, light radiates from this place. How did it happen? Rwanda became a family once again."

How is Rwanda remembering?

The commemoration activities began with the flame-lighting ceremony at the memorial. The flame will burn for 100 days.

The 61-year-old president, who has led the country since 2000, then delivered a speech at the Kigali Convention Centre.

People hold candles in remembrance at a vigil at Amahoro Stadium

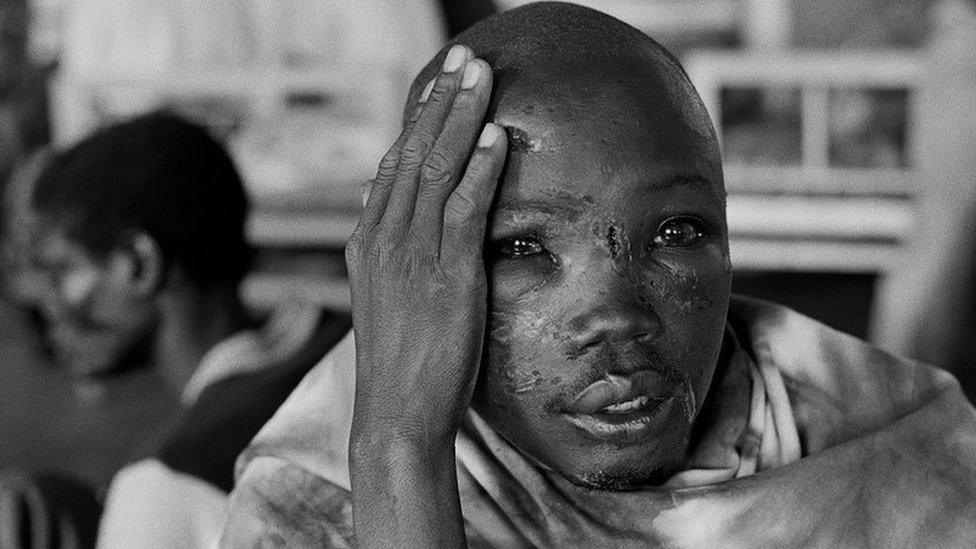

He said the resilience and bravery of the genocide survivors represented the "Rwandan character in its purest form".

"The arms of our people, intertwined, constitute the pillars of our nation," he said. "We hold each other up. Our bodies and minds bear amputations and scars, but none of us is alone.

"Together, we have woven the tattered threads of our unity into a new tapestry."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

He added: "The fighting spirit is alive in us. What happened here will never happen again."

Mr Kagame then led a vigil at the Amahoro National Stadium, which was used by United Nations officials to try to protect Tutsis during the killings.

About 2,000 people marched together on a walk of remembrance from parliament to the stadium, where candles were lit.

Cries for those who were lost

The BBC's Flora Drury in Kigali

There was a moment - when all the candles were lit, and their lights bobbed around the stadium, when people were taking pictures with their smartphones - when it was almost possible to forget the horror that brought thousands of people together on this warm evening in Kigali.

But then I turned to the man next to me, and asked him what tonight meant to him.

"Well," he said, "it's important." In the understated way which so many people in Rwanda speak he said: "I lost people. I lost my parents. I lost my siblings."

About 2,000 people attended the vigil

We had already heard the names of entire families wiped off the map read out, accompanied by a promise never to forget. We had watched students march in silence from the parliament to the stadium.

But it was as the final speaker took to the stage, to describe how he survived to grow up and give his children the names of the four siblings he had lost, that the emotion seemed to bubble to the surface, and anguished cries were heard above the crowd.

Sometimes on this day, my neighbour said, it is hard to keep the emotions in.

Who is attending?

A number of foreign leaders are in the country for the events. They are mainly African, although Prime Minister Charles Michel represented the former colonial ruler, Belgium.

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker also attended.

French President Emmanuel Macron did not go, however. This week he appointed a panel of experts to investigate France's role in the genocide.

France was a close ally of the Hutu-led government prior to the massacres and has been accused of ignoring warning signs and training the militias who carried out the attacks.

France was represented by Herve Berville, a Rwandan-born MP.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni was also absent. He has been accused of backing Rwandan rebels who oppose Mr Kagame.

The vast number of people attending were ordinary Rwandans, including those who lived through the slaughter.

Olive Muhorakeye, 26, told Reuters: "Remembering is necessary because it's only thanks to looking back at what happened [can we] ensure that it never happens again."

How did the genocide unfold?

On 6 April 1994, a plane carrying then-President Juvenal Habyarimana - a Hutu - was shot down, killing all on board.

Between April and July 1994, an estimated 800,000 Rwandans were killed in the space of 100 days.

Hutu extremists blamed the Tutsi rebel group, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). It denied the accusation.

In a well-organised campaign of slaughter, militias were given hit lists of Tutsi victims. Many were killed with machetes in acts of appalling brutality.

One of the militias was the ruling party's youth wing, the Interahamwe, which set up road blocks to find Tutsis, incited hatred via radio broadcasts and carried out house to house searches.

More on the genocide:

How did it end?

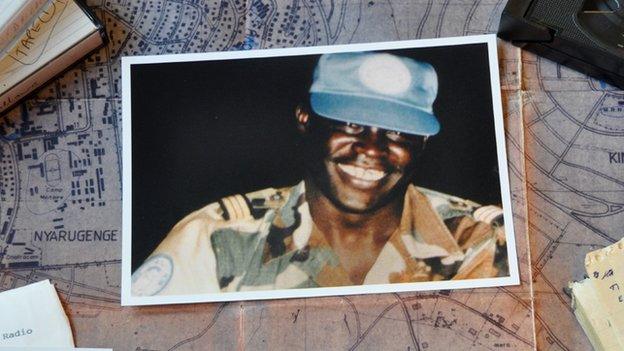

Little was done internationally to stop the killings. The UN and Belgium had forces in Rwanda but the UN mission was not given a mandate to act. The Belgians and most UN peacekeepers pulled out.

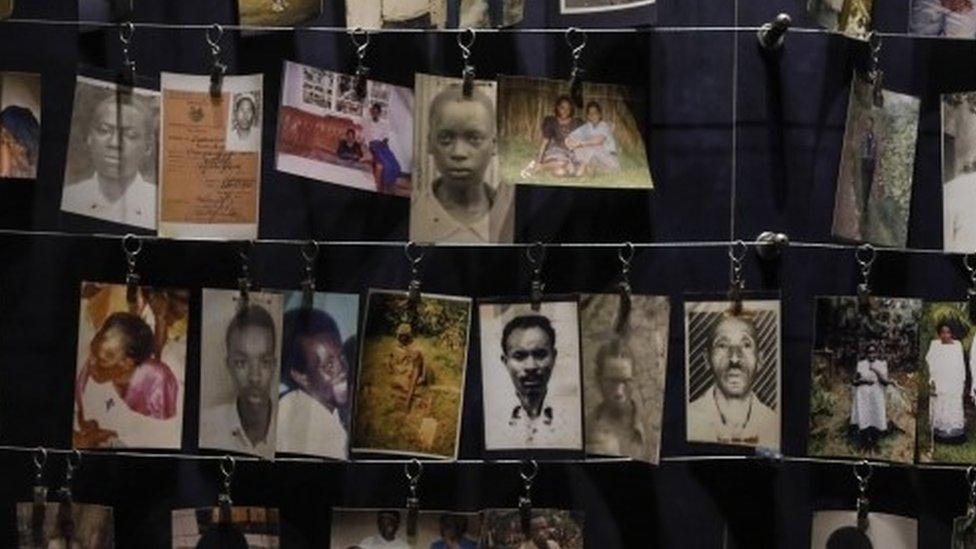

Pictures of victims at the Genocide Memorial in Kigali

The RPF, backed by Uganda, started gaining ground and marched on Kigali. Some two million Hutus fled, mainly to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The RPF was accused of killing thousands of Hutus as it took power, although it denies this.

Dozens of Hutus were convicted for their role in the killings by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, based in Tanzania, and hundreds of thousands more faced trial in community courts in Rwanda.

How is Rwanda now?

The genocide has cast a long shadow over regeneration and talk of ethnicity remains illegal.

But the country has recovered economically, with President Kagame's policies encouraging rapid growth and technological advancement.

He won a third term in office in the most recent election in 2017 with 98.63% of the vote.

Growth remains good - 7.2% in 2018 according to the African Development Bank.

But Mr Kagame's critics say he is too authoritarian and does not tolerate dissent.

- Published4 April 2019

- Published12 March 2015

- Published5 April 2014

- Published2 April 2014

- Published11 June 2012