Somalia's frightening network of Islamist spies

- Published

Somalia's militant Islamists remain relatively undiminished, despite a 12-year UN-backed campaign against them, largely thanks to its sophisticated web of spies, writes the BBC's Mary Harper.

Often, when I return to the UK from Somalia, I get a phone call from al-Shabab. It usually happens even before I talk to my family, while I am waiting for my luggage or in a taxi on the way home.

Once, after a trip to the south-western Somali town of Baidoa, I was given a detailed account of what I had done and where I had been.

"You walked to a bank but it was shut. You knocked on the doors and tried to open them. You took some photos," said the man from al-Shabab, an affiliate of al-Qaeda.

"Your bodyguards were not at all professional. They were wandering about, chatting amongst themselves with their guns slung around their shoulders, instead of keeping watch over you."

Mogadishu bears the scars of nearly three decades of conflict

When I ask members of al-Shabab how they know all these things, how they can be so accurate, my contacts simply tell me they have friends everywhere.

I tell them I am scared they know my itinerary so intimately, but they tell me not to worry as they have far more important targets than me. However, they do say I could be in "the wrong place at the wrong time" and suffer the consequences.

'They are everywhere'

I presume some of the people who track my movements in Somalia are part of the militant group's ruthless intelligence wing, the Amniyat. Others might be people who work on a "pay-as-you-go" basis, receiving small sums for imparting information.

Even more terrifying is the way the militants track people they want to recruit, threaten or kill.

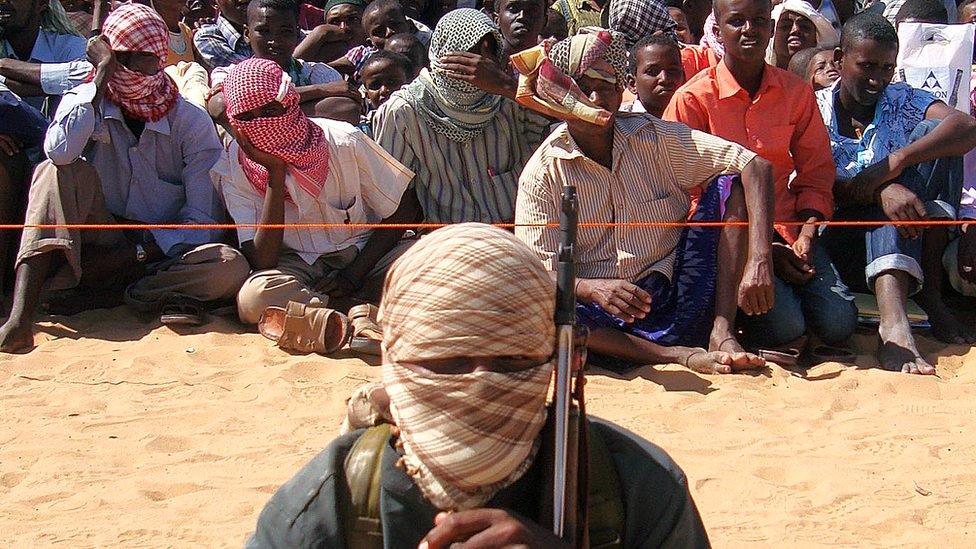

Al-Shabab approach families to recruit young fighters

"Al-Shabab are like djinns [spirits]. They are everywhere," said one young man the militants wanted to punish because he sold fridges and air conditioners to members of the UN-backed Somali government and the African Union intervention force [Amisom], both considered enemies by al-Shabab.

Another man who had defected from al-Shabab explained how, one day, a member of the group called him to tell him the colour of the shirt he was wearing and which street he was walking down on a particular day at a particular time.

Others have spoken about how militants come to their houses and places of work inside Mogadishu to threaten or try to recruit them. All this, despite the fact that the group "withdrew" from the capital in August 2011.

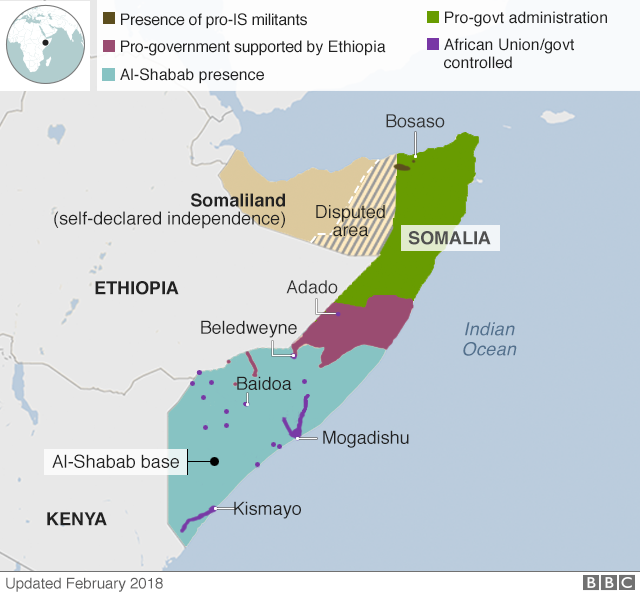

Al-Shabab at a glance:

Means "The Youth" in Arabic

Formed as a radical offshoot of the Union of Islamic Courts, which controlled Mogadishu, in 2006

Core fighters number between 5,000 and 6,000

Members of spy network number between 500 and 1,000

Main funding via tax collection and protection money

Controls most rural areas of southern Somalia

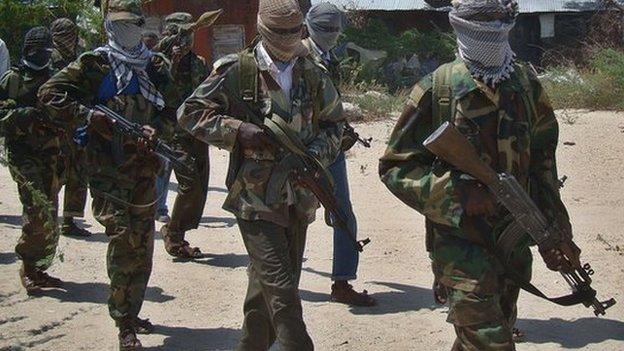

"The Amniyat is the veins of the organisation. It is all-powerful. If the Amniyat was destroyed, there would be no al-Shabab," says Hussein Sheikh Ali, a former security adviser to the Somali president and director of the Hiraal Institute, a Mogadishu-based think tank.

He says the Amniyat is more than an intelligence unit.

"It literally controls al-Shabab. As well as its core purpose which is intelligence gathering, it deals with sensitive areas of security. If a senior member of al-Shabab is sick or injured, the Amniyat will deal with it. It manages finances of a secret and delicate nature, and plans the big terror attacks inside and outside the country."

People in the Amniyat are better paid than other members of the movement. They have spread their tentacles far and wide, including in places considered to be safe.

'At home in enemy territory'

One time, when I didn't leave the heavily protected international airport, and stayed in accommodation on the base, a militant called to say it knew I had been in Somalia.

Mohamed Mubarak, a researcher based in Mogadishu, estimates that the number of people in the Amniyat ranges from between 500 and 1,000.

Al-Shabab wives have to help them by providing a bed for the night, feeding them, transporting things for them and passing on messages"

"They are designed to live in enemy territory. They spend most of their time in government territory," he says.

According to Mr Mubarak, women play a crucial role in helping members of the Amniyat.

"Women support the Amniyat. They are part of its infrastructure. Al-Shabab wives have to help them by providing a bed for the night, feeding them, transporting things for them and passing on messages."

The Amniyat is highly secretive. Its members hide their identities from each other. Mr Mubarak explains how Amniyat cells do not know the details of other cells. Members cover their faces when they meet amongst themselves, even within the same cell.

"Only their leaders know their faces," he says.

'Like Stalinist secret police'

The Amniyat has a number of different departments. The main one focuses on intelligence and counter-intelligence, while others deal with bombings and assassinations.

People who defect from al-Shabab are terrified the Amniyat will track them down.

Defectors in a rehabilitation centre said the only way they could be safe from al-Shabab would be to flee Somalia.

The security forces control very few roads between major towns in Somalia

"Al-Shabab calls me on the phone," said one man who had fought with the group for six years. "I will try to melt away in a big city like Mogadishu or Baidoa, but I am scared they will find me there. I will only be safe if I go to Europe or the Gulf."

More on life amid Somalia's conflict:

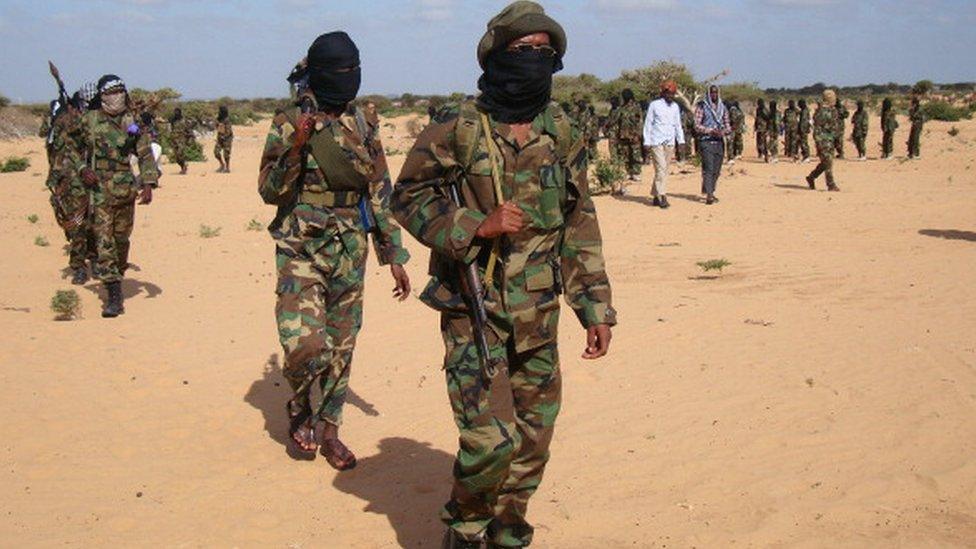

Although the US has increased airstrikes in Somalia in recent months, it is facing great difficulty in destroying al-Shabab. This is partly because so many members of the Amniyat hide in plain sight in government territory, making them impossible to target.

According to Richard Barrett, a former director of British global counter-terrorism operations who now works in Somalia, the Amniyat is "the elite of al-Shabab, with a reputation both inside and outside the movement as efficient, ruthless and disciplined".

"There is no doubt that much of al-Shabab's success in government-held areas can be ascribed to the Amniyat," he says. "It is a Stalinist secret police with extensive powers and operational latitude."

Mary Harper is the BBC World Service's Africa editor and author of Everything You Have Told Me Is True

- Published22 December 2017

- Published7 January 2019

- Published7 November 2015

- Published26 February 2014

- Published19 October 2016

- Published20 May 2015

- Published24 May 2015