Northern white rhinos: The audacious plan that could save a species

- Published

The future of the northern white rhino is looking bleak. Only two are left in the world - both are female. But scientists have an outlandish plan to save them from extinction.

When I went to meet the rhinos in Kenya, they began circling the car.

So I was alarmed when their caregiver, James Mwenda, opened the car door.

"We can get out of the car?" I asked.

"Yeah, they're calm," he assured me.

But when I did, one ran towards me - it didn't seem very calm.

I hid behind the other side of the car as Mr Mwenda tried to reassure me that they were not scared of humans, though it didn't stop me being scared of rhinos.

The rhino, called Najin, who had approached us was tame because she had been brought up in a zoo in the Czech Republic.

She now lives in a massive fenced off area of Ol Pejeta Conservancy in central Kenya.

Najin is one of two northern white rhinos left in the world

In 2009 she was one of four northern white rhinos, two male and two female, who were brought from the Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic to this large enclosure in an attempt to get them to breed.

The thinking was that if they were taken to a rhino's natural habitat this might change.

But it didn't work. The four mated but the two females, Najin and her daughter Fatu, did not give birth.

Then the two males died. First 34-year-old Suni, who died of natural causes in 2014. Then, four years later, 45-year-old Sudan was put down because of wounds to his skin that would not heal - and his muscles and bones had degenerated.

Now Najin and Fatu are the only northern white rhinos left in the world - and neither can carry a pregnancy.

Precious sperm

This has not deterred scientists from all over the world from trying to save the species - and they have come up with a rather extraordinary scheme.

It involves carefully preserved sperm - taken from Suni and Sudan and other male northern white rhinos before they died.

The dead rhinos' sperm was low quality

They had collected it with the intention of artificially inseminating the females, including southern white rhinos.

There are two sub-species of white rhinos in Africa - the near-extinct northern white rhino and the more prevalent southern white rhino.

However, these insemination attempts failed.

So they moved on to trying to make an embryo - an egg fertilised by sperm - in the lab.

That created another challenge: getting hold of the egg.

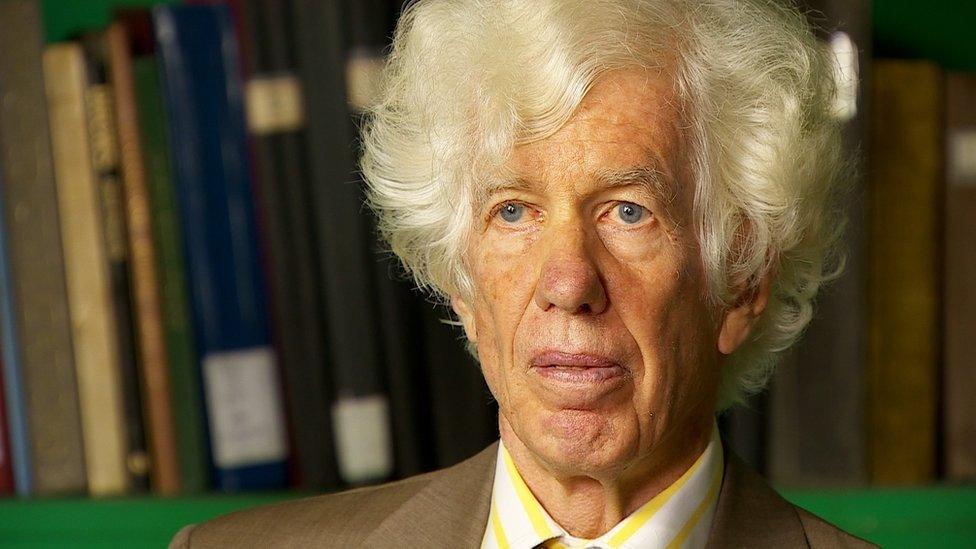

Dr Hilderbrandt (C) had less than two hours to collect eggs from Fatu - if he had made a wrong move he would have killed her

For the veterinary expert leading the process it proved very complicated indeed to reach the ovaries - where eggs are stored - as they are at least 1.5m (4.9ft) inside a female rhino.

Intestinal loops also get in the way, Dr Thomas Hildebrandt, from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) in Berlin, told me.

And a tube cannot be put into a rhino's vagina as can be done with humans and horses, he says.

In big cats, vets go through the abdomen to get to the ovaries, explains Dr Hildebrandt, who heads IZW's reproduction unit.

But this involves cutting the skin, something that cannot be done to rhinos as theirs is around 5cm (2in) thick.

While it protects them when they get into fights, it never heals so if cut they will eventually die.

Made of two subspecies: Northern white rhinos and southern white rhinos

Nicknamed:“Square-lipped rhinos”

Northern:Population two, under armed guard in Kenya

Southern:Estimated population 20,000, mostly in southern Africa

Differences:Northern are slightly smaller and less hairy than southern

Poachers:Target them for their horns to smuggle to Asia for remedies

Rhino horns:Made of keratin - the same substance as fingernails

So Dr Hildebrandt created an instrument to collect the eggs.

It was a tube, which enters through the anus, and has a long delicate needle at its end with which to pierce an ovary follicle, where an egg is stored. The needle is connected to a suction device which sucks the egg down the long tube.

"You need to operate it precisely," he explains about the instrument he has patented.

"Otherwise you can puncture a huge blood vessel which has a diameter of a child's arm".

That would result in internal bleeding and ultimately death so he uses a 4D ultrasound scanner, enabling him to see everything during the procedure.

If done correctly the effect on the rhino is minimal, Dr Hildebrandt says.

But the operation can be no longer than two hours as that is how long a rhino can be safely anaesthetised.

Last year, he managed to extract 19 eggs in total from both Najin and Fatu.

Mad dash to Italy

The next step was to fertilise the egg with the sperm.

For this pioneering work, they needed an in vitro fertilisation (IVF) expert.

Cesare Galli, based in the Avantea private lab in Italy, fitted the bill.

So as soon as the eggs were collected, they had to be rushed from Kenya to Italy.

Dr Hilderbrandt and Prof Galli had to get the eggs to Italy as quickly as possible

Prof Galli had struggled to make embryos from other rhino species in the past as sperm from rhinos tends to be of a low quality as it is mixed with urine.

"That's because, to get the sperm, they go up the rectum and electrocute the rhino to make the sperm come out, this method makes sperm and urine and other liquids come out altogether."

Dr Galli took years to perfect the method with Sumatran rhinos and southern white rhinos, making a breakthrough by electrocuting an egg to get it and the sperm to form an embryo.

The practice paid off.

With the rarer northern white rhino sperm and eggs he was confident he knew what would work.

He made two embryos with the first delivery of eggs in August 2019 and one more embryo with the second delivery four months later.

They are currently being preserved in his lab.

To grow, these embryos need a womb - but neither Fatu's nor Najin's are suitable.

More about conservation:

Nineteen-year-old Fatu has never had a calf despite mating.

When vets gave her an ultrasound they found she had no lining on her uterus, meaning she cannot carry a pregnancy to full term, said Stephen Ngulu, a vet at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy.

Fatu's 30-year-old mother, Najin, has weak hind legs - as issue because when rhinos are pregnant the hormone progesterone changes the dynamics of their legs.

"If she falls down and you can't get her up and then that's it - you lose her and you lose the baby," Dr Ngulu says.

They are not going to take that risk.

Instead they plan to use southern white rhino surrogates.

A handful of female southern white rhinos have been fenced off and are lined up to be surrogates

But Dr Galli says there is still so much they don't know about the reproductive system of rhinos.

Attempts in the past to put embryos in southern white rhinos in zoos have failed.

One of the things the scientists are struggling to work out is the timing to implant the embryo.

They need to know exactly when the body is best ready for it to attach to the uterus lining.

In women, the menstrual cycle determines when to implant an embryo.

Implanting after sex

But not all animals have menstrual cycles - some animals, including cats, release their eggs when they mate.

If this is also true for rhinos then it is possible to use sexual intercourse as an indicator, Dr Galli explains.

In other words, it may be possible that the scientists increase the chances of the surrogate carrying the pregnancy through to birth if they implant the embryo after she has had sex.

The adult males have all been taken out of the large enclosure leaving the adolescents to play in mud

This hunch has led them to set the scene for the next stage in their elaborate plan.

Four wild female southern white rhinos have been enclosed with their offspring in their natural habitat not far from the last two remaining northern white rhinos.

The next step is to put a sterilised southern white rhino in with the females - and would-be surrogates.

"So if you see that bull mounting, you say: 'Rhino's ready.' You dart that rhino, you put the embryo in. That's the dream," says Dr Ngulu.

I went to see the potential surrogates.

One of these rhinos could stop a species from going extinct

Unlike Najin and Fatu, they are wild so they can be hard to track down in the sprawling enclosure.

When we found them, on the second day of searching, I couldn't help but think that these rhinos do not know it yet, but one of them may save a species from extinction.

You may also be interested in:

Could farming rhinos save them from extinction?

- Published30 October 2011

- Published5 February 2018