AI in Africa: Teaching a bot to read my mum's texts

- Published

Bonaventure Dossou is working on an AI model to help translate Fon to French

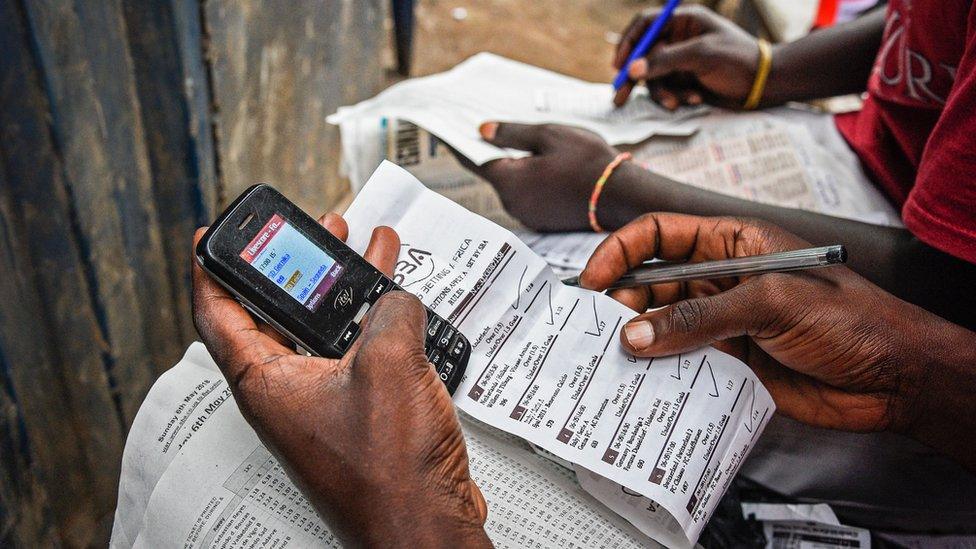

Bonaventure Dossou has been thinking a lot about how to improve phone conversations with his mother.

She often sends him voice messages in Fon, a Beninese language, as he is away studying in Russia. He, however, does not understand some of the phrases she uses.

"My mum cannot write Fon and I don't speak the language very well but I'm fluent in French," Mr Dossou told the BBC.

"I frequently ask my sister to help me understand some of the phrases mum uses," he said.

Nùkócé nɔn yìnMy name is

Oun yìn wàn nouwé I love you

Ouh fɔn gangjiI'm fine

NùnùɖùFood

Improving his Fon through study is out of the question because like hundreds of other African languages, it is mostly spoken and rarely documented, so there are few, if any, books to teach the grammar and syntax.

Driven by curiosity and powered by data scraped from a Fon to French Jehovah Witness Bible, Mr Dossou and Chris Emezue, a Nigerian friend, developed an Artificial Intelligence (AI) language translation model, similar to Google Translate, which they have named FFR. It is still a work in progress.

The two students are among several AI researchers using African languages in Natural Language Processing (NLP), a branch of AI used to teach and help computers understand human languages.

Had the world not ground to a halt following the Covid-19 pandemic, Mr Dossou and Mr Emezue would have presented their creation to hundreds of participants at one of the world's biggest AI conferences, ICLR,, external in Ethiopia's capital, Addis Ababa, this week.

It would have been the first time the event was held in Africa.

Instead of cancelling the event the organisers decided to hold it virtually.

You may also be interested in:

AI innovations have been singled out as the driver of the so-called fourth industrial revolution which will bring radical changes to almost every aspect of our lives including how we work.

Some analysts have called big data, which power AI systems, the new oil.

At the moment, Africa is seen as losing out in playing a role in shaping the AI future, because the majority of the continent's estimated 2,000 languages are categorised as "low-resourced" meaning there's a dearth of data about them and/or what is available has not been indexed and stored in formats that can be useful.

Fixing the languages gap

African languages are not considered when building NLP applications like voice assistants, image recognition software, traffic alerts systems and others.

But African researchers are working to eliminate this handicap.

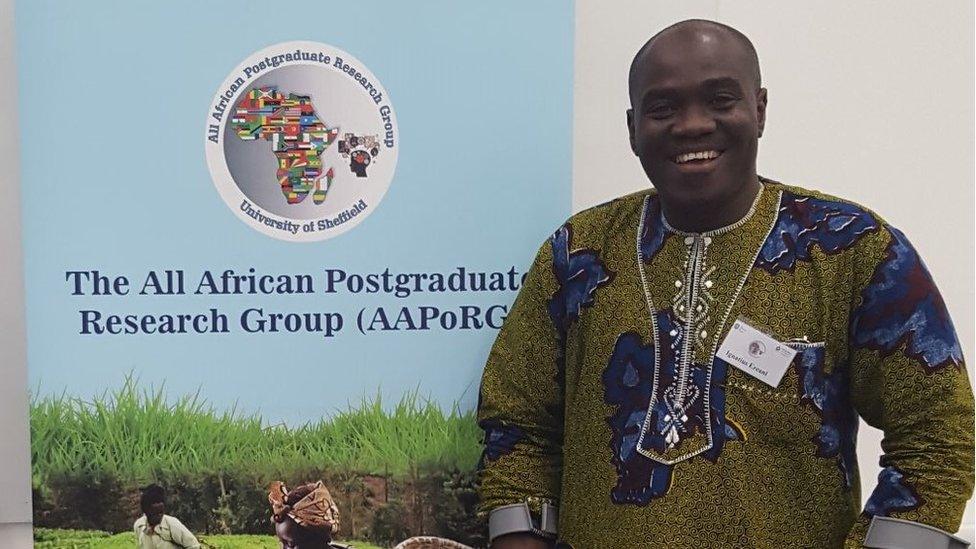

"We are focused on placing Africa on the NLP and AI research map," Dr Ignatius Ezeani, from the University of Lancaster, told the BBC.

"Unless you have your language resources publicly available, free and open, researchers will not have the data for creative solutions on the fly. We will always have to depend on, say, Google to determine the direction of research," Dr Ezeani said.

Dr Ezeani is working on a machine translation project of Igbo to English

The conference in Ethiopia was set to be a big deal for African researchers who, among the other challenges they face, have been denied visas to attend past ICLR conferences held in the US and Canada, locking them out of global AI conversations.

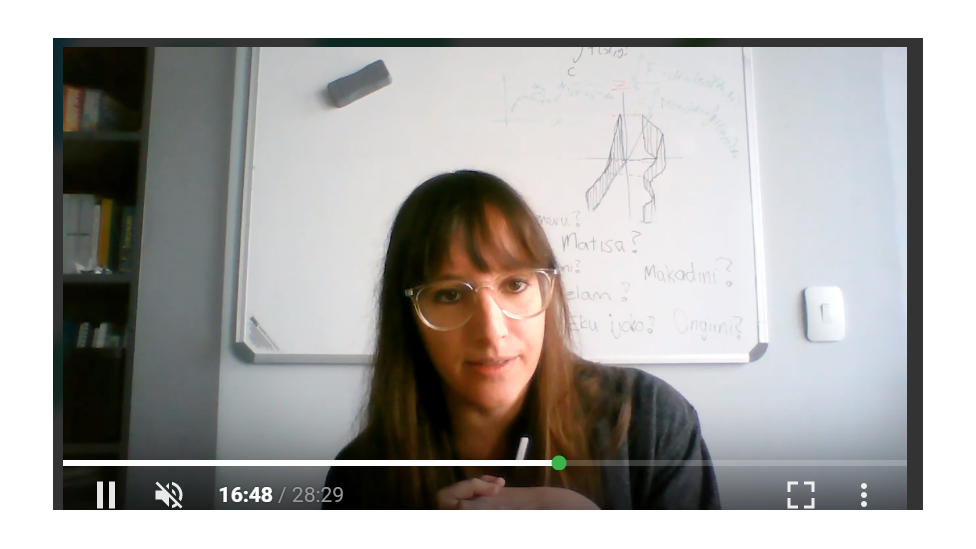

"Not having the conference in Addis was a huge blow, it would have provided a massive shift in the diversity of the conference," Jade Abbott, founder of Masakhane, a research movement for machine translation for African languages, told the BBC.

Masakhane, which means "We Build Together" in isiZulu, has 150 members in 20 African countries. Its membership is open to anyone who is interested in language translation.

"We are building a community of people who care about African languages and are keen to build translation models, 30% of the world's languages are African, so why don't we have 30% of NLP publications?" Ms Abbott asked.

Jade Abbott presenting her talk about Masakhane at the ICLR virtual conference

The network focusses on promoting language translation for Africans by Africans and is encouraging open sharing of resources and collaboration to help researchers build upon each other's work.

However, most of the time it means starting from scratch.

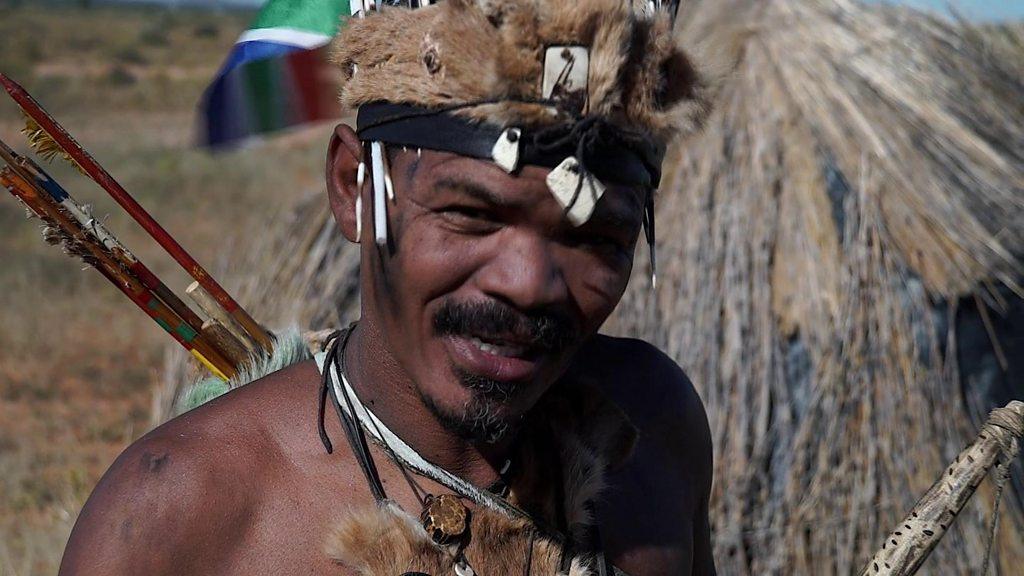

A Masakhane affiliated researcher, for example, is currently collecting data from speakers of the Damara, a Khoisan language - famous for its click sound - in Namibia, Ms Abbott said.

So far Masakhane members have done 35 translations of 25 African languages, she added.

A guide to Khoisan culture and language

Apart from Masakhane there are other initiatives building and strengthening the networks of AI researchers on the continent:

Deep Learning Indaba, which promotes AI in Africa and holds an annual conference

Data Science Africa, which connects the continent's researchers

BlackinAI, an initiative that promotes inclusion of black people in the field of Artificial Intelligence

Dr Ezeani calls them "silent struggles" of Africans working in the AI field.

He sees these engagements as helping to expand the continent's capacity both in terms of building AI infrastructure and the skills of researchers and developers.

"This is essential not just for recognition but for actually addressing our local challenges for example in health, agriculture, education and governance with home-grown and targeted solutions," he said.

"Maybe we can also take ownership and control the narrative at some point," he added.

Hey Alexa, do you speak Igbo?

Dr Ezeani is currently working on a machine translation of Nigeria's Igbo language to English.

"In five to 10 years, I think I'll be able to interact with Alexa in Igbo or indeed any minority language which will be a huge and fulfilling achievement," Dr Ezeani said.

Currently, none of Amazon's Alexa, Apple's Siri and Google Home, the main players in the global voice assistants market, support a single native African language. Google Translate is enabled for 13 African languages, including Igbo, however it is far from perfect.

Dr Ezeani said that the work that he and others are doing might tempt tech companies to integrate African languages into their devices.

He however cautions that African researchers working in the AI field should be driven by original ideas "that are actually useful to the people" and not pursue vanity projects.

"We can check whether, for example to see if, Igbo-to-Yoruba and vice-versa translation is actually more useful than Igbo-to-English; or whether speech or visual-to-text systems are more required than text-to-text," he said.

Mr Dossou (L) and Mr Emezue (R) hope to expand their project in Africa

As for Mr Dossou and his co-creator, Mr Emezue, they have big ambitions for FFR if they can secure funding.

They see Fon, a Bantu language spoken by more than two million people in Benin, and also parts of Nigeria and Togo, as helping them expand their work in other markets.

Fon is part of the Niger-Congo family of languages, meaning it shares a common ancestral lineage, with languages spoken in parts of West, Central, East and Southern Africa.

But for now their focus is to continue to train FFR to get better at translating daily conversation.

"Maybe in the next one year or so my mum's [voice] messages in Fon would be translated into text in French," Mr Dossou said.

- Published18 April 2019

- Published14 June 2016

- Published12 November 2019

- Published22 October 2018

- Published31 January 2019

- Published5 May 2018

- Published29 June 2016