Coronavirus and South Africa's toxic relationship with alcohol

- Published

South Africa's ban on alcohol during the coronavirus pandemic has prompted the BBC's Vumani Mkhize to reflect on why he and his country have such a toxic relationship with drink.

I was a 17-year-old in my penultimate year at school when I had my first blind-drunk experience, which led to my expulsion in 2002.

I was returning to Ixopo High School in KwaZulu-Natal province, which is surrounded by undulating green hills so famously described by anti-apartheid writer Alan Paton in the seminal novel Cry, the Beloved Country.

Paton was actually a teacher there in the 1920s and a handwritten first page of his novel hung in the school library. It made me want to emulate him - to have pages from a book I would write on the library's walls. But that was before I got distracted.

Disembarking from the minibus taxi after the school holidays, my best friend and I took off our ties and blazers and headed straight to the town's nearest bottle store where we bought two quarts of beer and a half-bottle of vodka.

I wore the blackouts as a misguided badge of honour"

The shop assistant had no qualms about selling alcohol to two wet-behind-the-ears boys, which says a lot about how negligent some establishments can be when it comes to serving underage children.

We drank behind an abandoned building - and I loved the feeling immediately, even if I wasn't so enamoured with the taste.

By the time we dragged ourselves up the hill to the boarding school, it was dark and the gates were closed. The headmaster was summoned; our fate sealed.

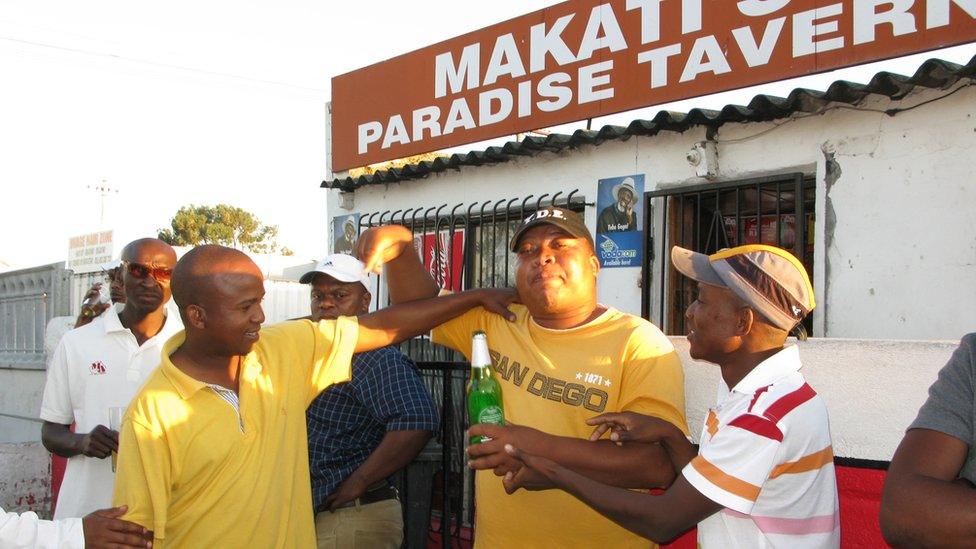

Shebeens are part of the drinking culture in South Africa's townships

I wish this had been the last such incident, but in the years to come I had many more blackouts and unseemly experiences.

But I felt no shame - I wore the blackouts as a misguided badge of honour, shared amongst friends while boasting how many cases of beer I drank in a weekend.

Apartheid-era drinking ban

In the broader South African context my experience is not unique and I'm sure countless people will have more harrowing stories to tell.

Workers on vineyards were once paid partly in alcohol; it was outlawed in 1961 but the practice continued until the end of apartheid

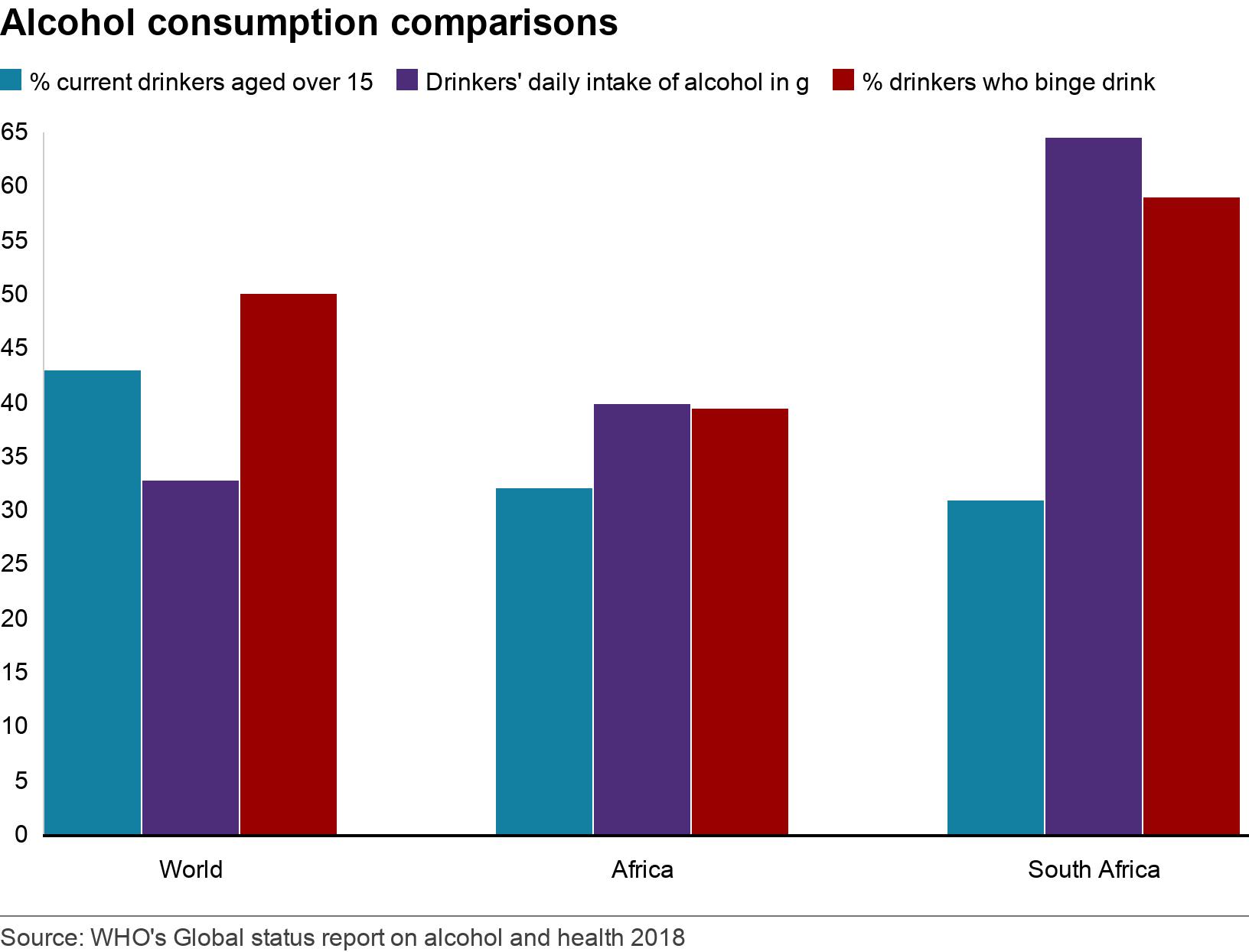

The paradox when it comes to South Africa's drinking culture is that while the majority of adults abstain, those that drink, do so heavily.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies the majority of drinkers in the country as binge drinkers.

This means around 59% of alcohol consumers drink more than 60g of pure alcohol on at least one occasion a month - that is six alcoholic drinks, four more than the daily recommended amount for men.

South African Medical Research Council's Charles Parry, who has spent more than two decades researching the country's fraught relationship with alcohol, believes there's an inextricable link between our drinking culture and our past.

"There was a period of time when alcohol was not available to black South Africans," Prof Parry tells me about the days before white-minority rule ended in 1994.

This led to drinkers going to illegal bars, with many black people seeing it as an act of defiance against the apartheid regime.

South Africa's Gabola church believes in connecting with God by consuming alcohol.

In the Cape Winelands, coloured (mixed-race) labourers were often paid in alcohol in what was called "the dop system". Although long since abolished, the harmful legacy of that system is still pervasive in many coloured communities across the Western Cape.

While restrictions on alcohol in the past were largely based on racist policies, current restrictions are a matter of life and death.

South Africa's coronavirus crisis:

Our unhealthy relationship with alcohol prompted the government to institute a very unpopular nationwide ban from the early days of the pandemic, in March.

On 1 June, the sale of alcohol for home consumption was allowed again, only for the ban to be reinstituted just over a month later.

When alcohol went on sale again in June it led to a resurgence in trauma cases

South Africa is currently battling the world's fifth largest Covid-19 outbreak, with more 500,000 confirmed cases.

The rationale behind the prohibition was to free up hospital beds in trauma units across the country - action vindicated by what doctors saw at our public hospitals.

"Our modelling found that we have a very high level of alcohol-related trauma in South Africa, which we calculated at over 42,000 presentations per week, and that [trauma cases] dropped by 60% to 70% in 'Level 5' [when the first ban was imposed]," Prof Parry told the BBC.

"What happened with the unbanning of alcohol on 1 June, was suddenly a huge resurgence in alcohol-related trauma and fatalities."

Taverns under threat

The ban has clearly alleviated pressure on the fragile health system, but from an economic perspective it has been catastrophic.

I feel like the bread has been taken from our mouths"

The alcohol industry supports more than a million jobs, and contributes around 3% to GDP. The continent's largest brewer, South African Breweries (SAB), says it is halting 5bn rand ($285m, £215m) of planned investment because of the ban.

"The cancellation of this planned expenditure is a direct consequence of having lost 12 full trading weeks, which effectively equates to some 30% of the SAB's annual production," Andrew Murray, the brewer's vice-president of finance, said in a statement last week.

Heineken, South Africa's second-largest brewer, has also announced that it will shelve plans to build a new 6bn-rand brewery in the port city of Durban - along with the creation of around 400 posts in an industry that has haemorrhaged more than 100,000 jobs since the end of March.

Restaurants have also lamented the ban - around 60% of their revenue comes from selling alcohol - with many having already shut their doors for good.

Restaurant workers have been calling for the alcohol ban to be lifted

Township taverns, or shebeens, are also battling for survival.

Mojela's Place in Tembisa, a vibrant township north of Johannesburg, is one of more than 34,000 registered taverns nationwide.

It is run by Kagiso Mojela and his father, who have converted a section of their home into a place where locals can drink beer while watching football.

They also have a shipping container to store the alcohol and the rumbling fridges. It is stacked with boxes of unsold beer.

"I'm concerned because if it expires it will make me go and look for a loan from the bank so I can restock again. So I would have lost stock of over 160,000 rand," Mr Mojela says.

"I feel like the bread has been taken from our mouths."

Growing calls to end the ban

It is a view echoed by Lucky Ntimane of the South African Liquor Traders Association, which represents licensed taverns.

He says more than 150,000 people rely on selling alcohol in order to feed their families and feels the government's attitude and failure to consider traders in townships shows "the total disdain in which they hold the entire industry".

Banning the official sale of alcohol has led to a thriving black market

In the lives vs livelihoods debate, a growing cacophony of voices is calling on government to end the alcohol ban.

Even medical experts like Prof Glenda Gray, the president of South African Medical Research Council and an adviser to the government on its Covid-19 response, agrees.

"We have achieved impact by having a curfew and prohibition on alcohol. We have achieved the lives and now we need to look at livelihoods."

Government is said to be losing around $635m a month on taxes and the country faces a deep recession, with the central bank projecting a contraction of more than 7% this year.

The unemployment rate - already at 30% - is expected to rise significantly by December, with some economists suggesting it could hit 50%.

Experts like Prof Parry also say poverty, depression and a sense of hopelessness drive a culture of drinking.

And the ban has given way to a thriving black market, a throwback to the days of apartheid.

I finally sobered up five years ago - more than a decade after my first schoolboy binge. However, if I was still a drinker, I would have found a way to get my hands on it somehow - the ban would have been unlikely to get me to give up.

I may have turned off my tap, but there are more than a million people who are begging the government to turn the tap back on again - with so many jobs at stake.

GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the coronavirus pandemic

GLOBAL TRENDS: Where are cases rising and falling?

TRACKER: Coronavirus cases in Africa

- Published11 May 2020

- Published3 July 2020

- Published27 July 2020

- Published31 May 2020

- Published9 July 2024