Letter from Africa: How a text book exposed a rift in Sudan's new government

- Published

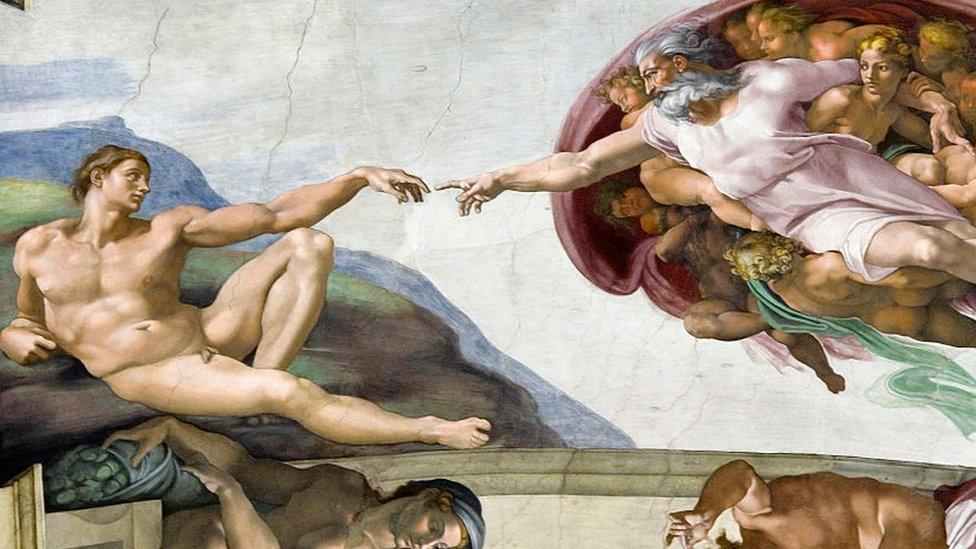

Some teachers came out to protest against the inclusion of The Creation of Adam in a school text book

In our series of letters from African journalists, Sudanese writer Zeinab Mohammed Salih looks at the clash over what children should be taught in school in the post-revolution era.

The euphoria following the ousting of Sudan's long-serving President Omar al-Bashir has been replaced by the hard work of cementing the democratic revolution.

But a clash over the new school curriculum with some religious figures has exposed the tricky path that the transitional government is treading.

Last month, at Friday prayers in a mosque in the capital, Khartoum, an imam known for his support of Bashir passionately shouted "Allah, Allah, Allah" before encouraging the male worshippers to scream and cry over the inclusion of the famous Michelangelo painting The Creation of Adam in a post-revolution history text book.

Michelangelo's painting of the Creation of Adam was described as heretical

Imam Mohamed al-Amin Ismail believed the painting, which forms part of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, was a heretical image.

He also lashed out at Suna, the official news agency, for giving a platform to Omer al-Qarray, one of the people behind the new school programme, accusing him of promoting infidelity and atheism.

Following the imam's intervention, many other pro-Bashir imams joined him to launch a campaign against the new curriculum and Mr Qarray himself. His family later said that they had received death threats over his work.

Then, Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok froze the introduction of the new curriculum.

The row over what the next generation should be learning has exposed tensions at the heart of the new political settlement"

Mr Qarray, who belongs to the Republican Brotherhood - a Muslim group that has a progressive interpretation of Islam - resigned from the curriculum project in protest.

He felt that the prime minister had ignored him and other political parties, and only listened to extremists and pro-Bashir Islamist groups.

There was also a dispute over how to present aspects of Sudan's 19th Century history.

How the revolution unfolded:

December 2018 : Protests against bread price rises after government removed subsidies

February 2019: Bashir declares state of emergency and sacks cabinet and regional governors in bid to end weeks of protests against his rule, in which up to 40 people died

April 2019: Military topples Bashir in a coup, begins talks with opposition on transition to democracy

June 2019: Security forces open fire on protesters, killing at least 87

September 2019: A new government takes office under Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok as part of a three-year power-sharing agreement between the military, civilian representatives and protest groups

The row over what the next generation should be learning has exposed tensions between people from different political and social perspectives at the heart of the new political settlement.

Some former rebel groups which once had ties with Bashir's regime welcomed the prime minister's decision to halt the new curriculum.

For example, Sulieman Sandal, from the Justice and Equality Movement (Jem), whose children are living in Norway, backed Mr Hamdok and its leader Gibril Ibrahim, the recently appointed finance minister whose children are living in the UK and all studying secular curriculums, were then accused of hypocrisy.

Optimism about the future of the country accompanied the uprising in Sudan in 2019

Sharia was first introduced into Sudanese law in September 1983 during the rule of President Jaafar Numair. It was one of the reasons behind the long civil war with what was then the southern part of the country and is now South Sudan.

Islamic law was then suspended for three years during the democratically elected government of Sadiq el-Mahdi but was revived when Bashir took power in 1989 in a military coup backed by an Islamist party.

The transitional government that replaced Bashir has already shown its reluctance to tackle the thorny issue of Sharia, which is at the heart of the conflict with rebels in South Kordofan.

The most prominent rebel group there, the SPLM-N, has demanded that the government take a secular approach. Last year it rejected a peace deal agreed by other parties and accused the transitional government of colluding with Islamists.

The SPLM-N, which operates from an area inhabited by many Christians and other non-Muslims, has been fighting for those who are politically and economically marginalised.

Alcohol ban partly lifted

The new transitional government has made some moves that make life easier for them.

Only six months ago, it dropped laws that prohibited non-Muslims from drinking alcohol, though it is still banned for Muslims.

But according to some reports, the flogging of drunken people and the arrest of alcohol brewers has not stopped in places on the outskirts Khartoum.

You may also be interested in:

The SPLM-N leaders believe that the only way to guarantee the rights of all and especially non-Muslims in Sudan is by having a secular government which will then create an economic programme that would ensure the fair distribution of the wealth and power in the country.

It is the only way that "non-Muslims will not be hurt", says Abbakr Ismail, a novelist and rebel leader.

A woman dubbed 'Kandaka', which means Nubian queen, became a symbol for protesters in 2019

The transitional government is made up of a coalition of groups - including generals who were once close to Bashir and some parties with an Islamist ideology.

With the current move on the curriculum, the government appears to be more concerned with being in harmony with more conservative views rather than becoming a representative government that reflects the diversity of the country racially, religiously and culturally, which would help stop the conflict.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

Related topics

- Published28 August 2019

- Published13 September 2023