Viewpoint: Self-defence not the answer to Nigeria's kidnap crisis

- Published

In our series of letters from African writers Nigerian journalist and novelist Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani reflects on a recent call for Nigerians to take security into their own hands.

The Nigerian government seems to have suggested that it can no longer be relied on to keep citizens safe.

Last week, the minister of defence had a message for communities that have suffered attacks by armed gangs: Defend yourselves, don't just sit and be slaughtered like chickens.

"We shouldn't be cowards," said Bashir Salihi Magashi, a retired major general.

"I don't know why people are running away from minor, minor, minor things like that. They should stand. Let these people know that even the villagers have the competence and capability to defend themselves."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

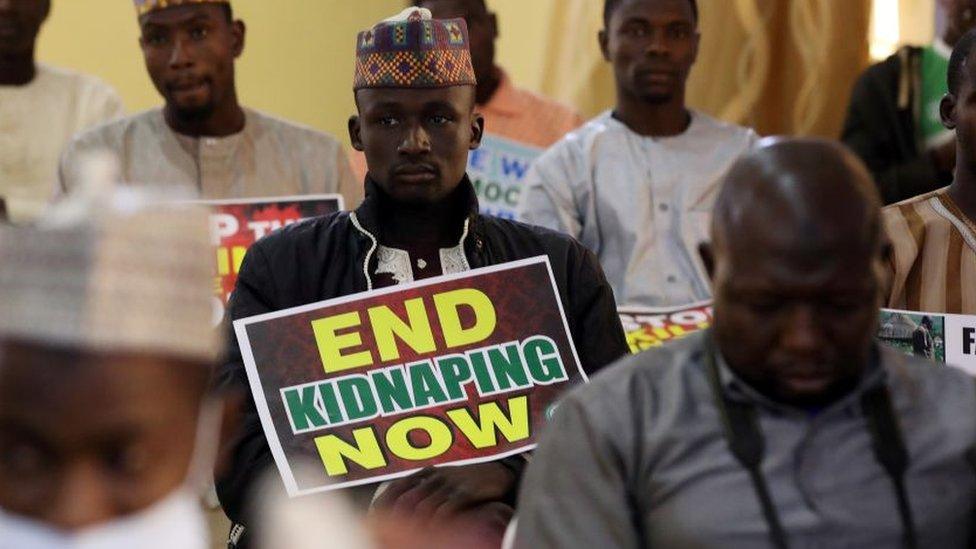

Mr Magashi's statement - which came hours after gunmen abducted dozens of people, including students, from a school in the north-central state of Niger - generated a storm of comments and criticism from Nigerians.

We are already used to taking charge of our affairs in areas where the government has not lived up to its responsibilities.

Many people in the country generate their own electricity, pump their own water, arrange private education for their children and so on.

No matter how determined an individual might be, they cannot defend themselves with just bare hands and bravery."

They would also gladly defend themselves against armed attackers.

But, under Nigeria's laws, it is now impossible to purchase a firearm. No matter how determined an individual might be, they cannot defend themselves with just bare hands and bravery.

Owning a weapon in Nigeria used to entail a complicated and torturous process.

Depending on the category of gun, you had to apply to your local government, your state police, or the presidency for a licence which had to be renewed annually.

New gun licences banned

The application was usually processed in about six months, and included a compulsory medical examination and psychiatric assessment.

Any gun owner planning to travel out of town was supposed to hand in their weapon to the police armoury for storage. And after the death of the owner, the weapon was to be returned to the state.

But, two years ago, President Muhammadu Buhari signed an executive order completely banning the issuing of gun licences - an action widely believed to be a response to the growing insecurity around the country and fears of uncontrolled bloodshed.

Armed gangs, popularly referred to by government officials and local media as "bandits", have been terrorising north-west Nigeria with robberies and kidnappings.

Politicians, entrepreneurs, commuters, and schoolchildren have been kidnapped at various times, and usually released after a ransom was paid.

Other regions face a plethora of security issues including: Boko Haram militants, farmer-herder clashes, kidnapping, piracy and armed robbery.

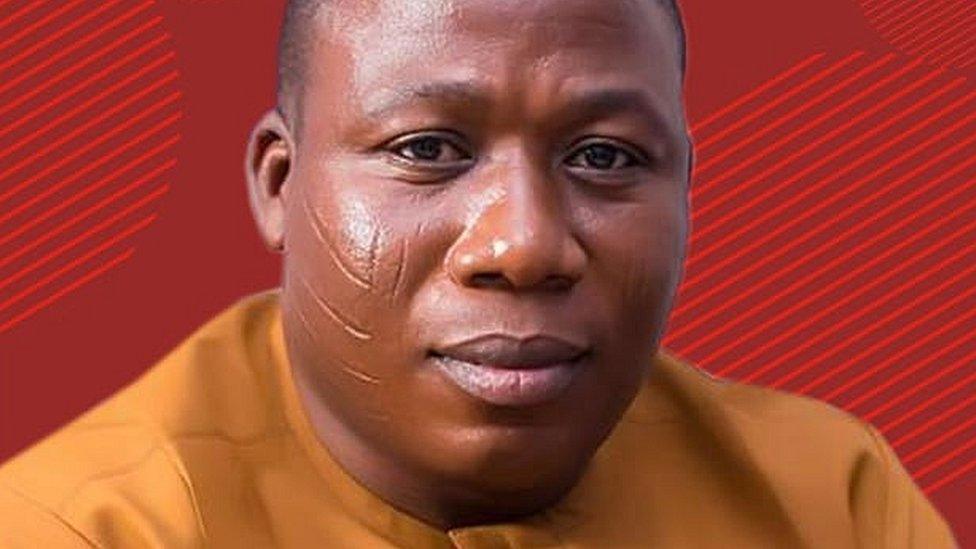

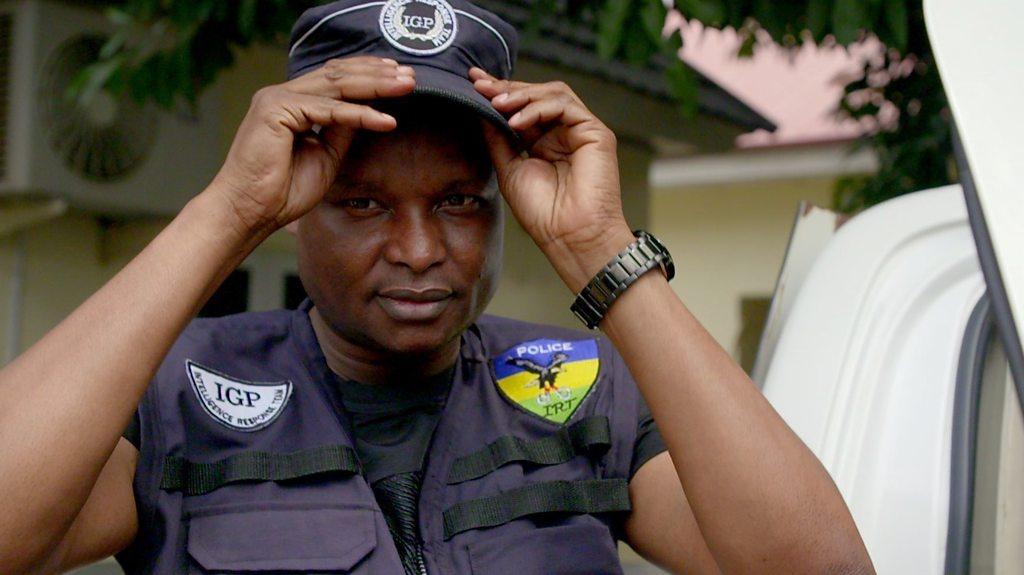

How a man dubbed "Nigeria's Supercop" is tackling kidnapping and armed robbery in the country.

The local media sometimes report the efforts of vigilante groups to safeguard their neighbourhoods, armed mostly with machetes and sticks.

But these weapons are no match for the superior power of the attackers, who obviously are not hindered by laws and licences when illicitly acquiring weapons like AK-47s and pump-action shotguns.

'Poor left unprotected'

"This executive order only targets legal guns and there is none to address those with illegal guns," said former lawmaker Nnenna Elendu-Ukeje in 2019, during a parliamentary debate about President Buhari's executive order.

As usual, it is the country's poorest who suffer most from the insecurity.

Hundreds of schoolboys who were kidnapped in December were returned safely

Top public servants in Nigeria are usually assigned armed police guards by virtue of their office.

Wealthy Nigerians often hire armed police escorts, even to private functions.

A top police official who chose not to be named told me that some influential Nigerians also sometimes circumvent Mr Buhari's order by purchasing firearms then bribing people to have the receipts and licences backdated.

"[The] majority of those who have licensed guns are well-to-do personalities," said lawmaker Sunday Adepoju during the 2019 debate. "For instance, in a community where there are persons with legal guns, the moment hoodlums come close and hear gunshots, they flee."

More weapons not the answer

However, worries in Nigeria about the dangers of easy legal access to firearms are valid, mirroring concerns in other parts of the world, especially the US where the debate is constantly raging.

With tight controls, Nigeria still experiences such wanton and ubiquitous violence.

One can only imagine how much bloodier things might be if anybody could just dig into the back of their jeans and whip out a pistol.

In the end, the safest option is for Nigeria's security agencies to rise to their responsibility of safeguarding the country from criminal elements, even if it means employing more people who can then be approved by law to bear arms.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

Related topics

- Published26 July 2021

- Published1 July 2019

- Published5 July 2020

- Published14 December 2020