Sea-cucumber divers off Liberia risk danger to feed a hunger in China

- Published

Abdoulaye Mansaray learnt about the business while processing sea cucumbers in Sierra Leone

Liberia may be sitting on a potentially valuable trade in sea cucumbers with China, but as journalist Lucinda Rouse reports, it could also threaten its coastal ecosystem.

In late 2019, Wilson Nimley, a field officer from the Liberian fisheries authority, stumbled across a group of strangers living in one of the remote coastal communities under his watch. They turned out to be divers from Sierra Leone, on a mission prospecting for sea cucumbers.

These slimy, sausage-shaped members of the starfish family have no local market but are a valuable commodity in China as both a culinary delicacy and a medicinal ingredient.

Entering mainland China from around the world via Hong Kong, some varieties can fetch up to $6,000 (£4,300) per kilogram.

Aliou Ba, or "Ali Diver", tests out the breathing equipment before the hunt for sea cucumbers begins

Neither Mr Nimley nor his superiors knew anything about the existence of these valuable creatures in Liberian waters.

But 37-year-old Abdoulaye Mansaray had been wise to the possibility since 2013, when Chinese divers operating a few hundred kilometres up the coast in the Sierra Leonean capital, Freetown, employed him to help process their sea cucumber catch. Initially earning $45 a month, he learned the trade and eventually formed his own team of local divers.

Armed with torches and breathing pipes attached to a diesel-powered air compressor, the group operates at night when the creatures emerge from under rocks.

It can be a dangerous business: several of the divers' wetsuits have been torn by the rocks, while forays into deeper water cause nosebleeds and headaches.

They continue to dive regardless and gather as many sea cucumbers as they can, returning to shore by early morning to unload their catch.

For every kilogram of wet cucumbers they bring, they earn $1.75. On a good night each diver might catch up to 50kg.

Abdoulaye Kanu, who processes the catch, earns much more now than as a telecoms sales agent

Then it is time for Abdoulaye Kanu, a former sales agent for a mobile phone network in Freetown, to get to work.

The 35-year-old says he earns three times as much processing sea cucumbers for Mr Mansaray.

He sits with a large bowl at his feet and methodically picks up the creatures one by one, using a sharp knife to release their innards before boiling them in a drum over a wood fire.

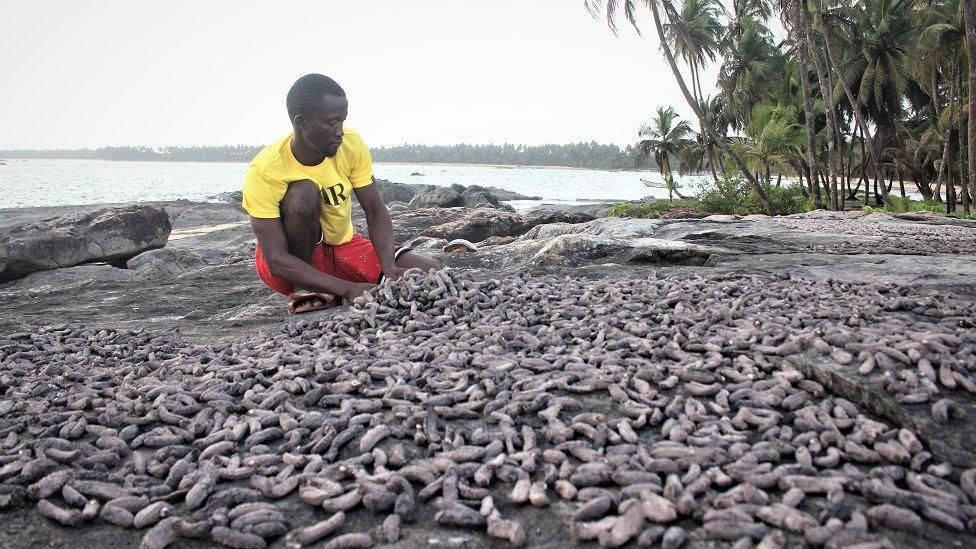

Once cooled, the cucumbers are smothered in salt and finally laid out to dry in the sun. By the time they are ready for export, the specimens are hard and shrivelled; their weight reduced by a factor of 30.

Vital sand cleaners

Sierra Leone's sea cucumber stocks have been over-fished, forcing the divers to prospect further afield. It is a common trend: some 70% of the world's sea cucumber fisheries are either fully or over-exploited.

In China - the world's biggest sea cucumber market - there are no natural populations remaining, according to marine biologist and sea cucumber expert Dr Mercedes Wanguemert.

The problem in West Africa, says Dr Wanguemert, is a lack of information.

"No-one knows the species being fished or the size of the stocks," she tells the BBC.

In tropical areas such as Liberia, "a maximum of 10% of the population can be caught in order to maintain healthy levels".

Sea cucumbers play a critical role in keeping marine ecosystems healthy.

They act as a filter, feeding on organic matter and microalgae and excreting "clean" sand. Among other benefits, they maintain oxygen levels and the pH of the water.

The sea cucumbers are left out to dry after being caught

Removing too many sea cucumbers, warns Dr Wanguemert, has repercussions for all levels of the ecosystem. Algae are the first to die, which removes the source of food for small fish species, in turn creating scarcity for larger ones.

The best option for Liberia, she recommends, is a moratorium: "Stop fishing for two years while stocks are studied."

The Liberian government is aware of the risk, according to Alexander Dunbar, director for policy, planning and investment at the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Authority (NaFAA).

"If not managed properly, a lot of our fisheries and the livelihoods that depend on them could collapse."

Mr Dunbar says NaFAA is taking a precautionary approach when it comes to licencing.

It has partnered with an academic research team collecting data to inform the development of a sustainable management plan for the new sea cucumber fishery: Liberia's first ever species-specific plan.

Job potential

Mr Mansaray's licence is conditional on his co-operation and provision of catch figures. No-one else will be permitted to dive while the research is underway and until stock sizes have been established.

The divers inspect the catch as it is being processed

For Mr Dunbar there are positives of a healthy sea cucumber trade: "If we manage it properly it will create jobs for Liberia and attract foreign direct investment in the fisheries sector."

But at present Liberians are excluded, lacking the equipment and know-how to dive and process, along with the trade links.

Unlike Sierra Leone, Liberia requires divers to be licensed, but no tax revenues are collected on sea cucumber exports.

And while local communities are willing to accommodate the strangers, the benefits to them stop at the two smartphones gifted by Mr Mansaray and a share of food.

The price the locals would have to pay should more divers arrive and disrupt their subsistence fishing would be far higher.

You may also be interested in:

A small group of townspeople is sitting by the divers' secluded beach camp.

One of them, Edward Nagbe, says they have observed a handful of groups passing through in recent years: "We didn't know the importance [of the sea cucumber] until a Chinese man arrived, and he did not go into detail about what it means, only that it can go in medicine."

The locals appear keen to get involved.

Although consumer demand for sea cucumbers is growing, Mr Mansaray believes the variety in Liberia is too small and hence not sufficiently valuable to garner interest among serious Chinese investors for much expansion.

'Sea cucumbers changed my life'

Aliou Ba, who goes by the name of "Ali Diver", hopes the trade will continue long enough to allow him to follow his dreams of eventually opening up a small shop in Freetown.

The eldest of the divers at 39, he says the late hours and other dangers do take their toll.

Mohamed Kakay is happy to have a job diving despite the dangers

Like several of his colleagues he has a persistent cough and is concerned about the effects of the work on his health.

It is not an unfounded fear, with a risk of lipoid pneumonia from inhaling the diesel fumes emitted by their rusting oxygen compressors.

"I'm lucky now, I'm young, so it can't infect me," he says. "But at 60 or 70 years the infection will come."

It came earlier for Mr Mansaray, who has not dived since 2014 when he developed pneumonia and was seriously ill for almost a year.

But in spite of the risks, some of the divers, including 32-year-old Mohamed Kakay, are grateful for the work in the absence of anything better.

"I was on the streets with my friends, playing bad games with police problems," he recalls.

"The sea cucumber job changed my life. It's a nice job, a fine job and has greatly helped my family."

Related topics

- Published13 February 2024