Macron's blunt style may harm bid for new African chapter

- Published

French President Emmanuel Macron has once again resorted to outspoken language as a tool of diplomatic strategy, this time targeting the president of the Central African Republic (CAR).

He described Faustin-Archange Touadéra as a "hostage" of Wagner, a Russian military contractor that has been helping the CAR government fight rebels threatening to overrun the capital, Bangui.

Paris is also angered by the anti-French social media messages that emanate from sources close to Mr Touadéra, stirring up resentment against the former colonial power.

It was the intervention by French and African troops in 2013 that saved CAR from a potentially genocidal civil conflict and created the conditions for the democratic elections that brought Mr Touadéra to power in 2016.

But the CAR now relies heavily on Russian military expertise and has also signed mining deals with Russia, allowing it to explore for gold, diamonds and uranium.

Uneasy about the lurch towards Moscow and angered by the anti-French rhetoric, Mr Macron has suspended budget support for the CAR government.

About 1.4 million people have been displaced by conflict in the CAR, the UN says

Mr Macron also concluded that a blunt public warning was needed, through a now widely publicised 30 May interview with the Journal du Dimanche (JDD).

His outspoken words met with no direct response, although Mr Touadéra's government says its arrangement is with the Russian defence ministry rather than Wagner.

But the Central African head of state was not the only target of his plain speaking.

He warned Mali - where interim Vice-President Colonel Assimi Goïta has staged a fresh coup to depose the president and prime minister - that French troops deployed to help in the fight against militant Islamists could be pulled out if the West African state went down the path of Islamist radicalism.

The JDD interview was widely reported in Francophone media, external. Mr Macron certainly knows how to get attention.

While warning Mali's transitional leaders against cutting a soft deal with jihadists, his comments perhaps also sought to reassure voters back home that French troops in the Sahel region were not being asked to put their lives on the line in vain.

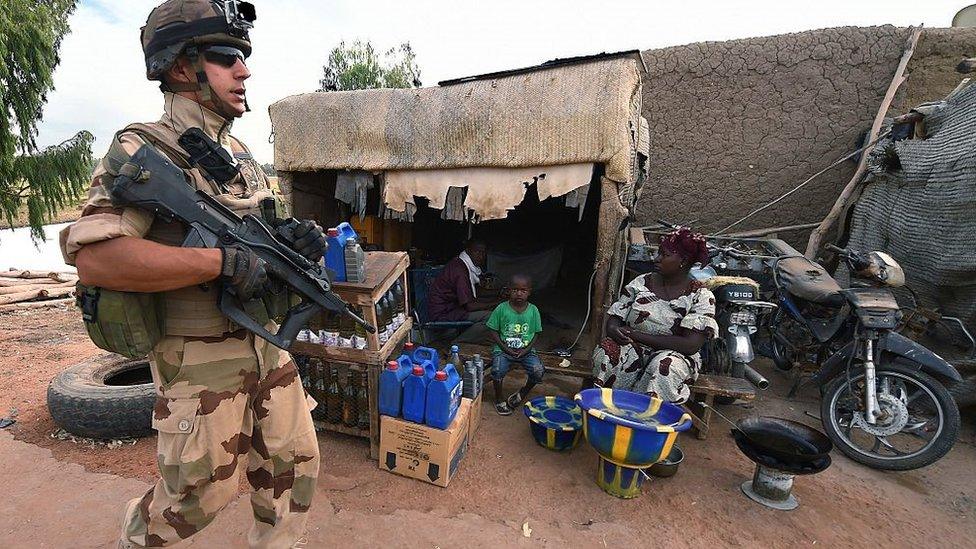

France has more than 5,000 troops in Mali

Mr Macron's style certainly contrasts with the clubby networking that used to characterise so much of the relationships between French presidents and African political élites - a sometimes complacent culture, summed up in the term Françafrique.

This tended to reinforce incumbent power rather than responding to wider demands for reform or social and economic development.

Macron's 'arrogant' style

Mr Macron has faced African issues head-on, and with a much greater degree of openness. He is not afraid to publicly make the case for change.

This can certainly produce results - as illustrated by a visit last week to Rwanda, where he made a straightforward admission of France's failings in the run-up to the 1994 genocide, in a gesture that aimed to lay the foundations for building a new relationship that moves forward from the bitterness left by past history.

French President Emmanuel Macron (L) visited the genocide memorial in Rwanda on 27 May

But his personalised style, with its direct language and occasional impatience with diplomatic protocol, is a high-wire act that can appear arrogant.

The four years of his presidential engagement with Africa have been marred by sporadic incidents of offence or high-handedness that fuel the always combustible sense of resentment towards France as a former colonial power, particularly among younger Africans.

Return of looted artefacts

But those four years have also been marked by a brave readiness to pro-actively tackle awkward issues and explore new ways of doing things.

Mr Macron has commissioned academics to write three independent reports researching French behaviour: during the bloody independence conflict in Algeria; the Rwanda genocide and the potential return to Africa of historical and cultural artefacts taken to France during the colonial era.

You may also be interested in:

His blunt admission of French failure in Rwanda was based on the findings of the Vincent Duclert report, which has been published in full.

After receiving historian Benjamin Stora's report on Algeria in January, the French president said he would launch a series of initiatives based on its recommendations, a number of which would be organised by a Truth and Memory commission headed by Prof Stora.

Critics feel that Mr Macron has not fully grasped what is required, but the implementation of recommendations in partnership with Algeria may be hampered by the North African state's current internal political difficulties.

The restitution of cultural artefacts has already begun, with a sword handed over to Senegal and the crown from a royal dais returned to Madagascar, while arrangements are under way for the return of 26 items to Benin.

Senegal's President Macky Sall (R) called the return of the sword on 17 November 2019 a "historic day"

But beyond these cultural and symbolic gestures, Mr Macron is trying to strike a difficult balance, and one that would face any French president in 2021.

Paris policymakers believe that Africa is a continent of huge importance, a near neighbour to Europe with fast-growing populations and economies but facing deep development challenges.

Tension over 'colonial' currency

France, and indeed the European Union, should therefore remain heavily engaged - through political relationships, development assistance rising to 0.55% of gross national income in 2022 and a continued military presence, particularly to tackle militant groups and support efforts to stabilise the Sahel - a semi-arid stretch of land just south of the Sahara Desert which includes Mali, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mauritania.

But the very scale of this engagement can also leave Paris exposed to accusations of post-colonial interference.

This is well illustrated by efforts to reform the CFA franc, a currency used by 14 countries that is pegged to the euro under a French government guarantee - an arrangement that keeps inflation low but constrains monetary independence.

Many young people in Africa want to scrap the CFA franc, and its ties to France

Back in 2017 Mr Macron said that if West African governments chose to reform the currency, his country would support them. A limited first stage relaxation of French control was announced in December 2019.

But popular and intellectual demands for more far-reaching change persist and France continues to be accused of seeking to maintain indirect control - even though, in reality, the further reform depends on overcoming serious technical challenges, and political differences among West African governments.

In the Sahel some critics accuse Paris of keeping troops deployed to protect its economic interests. France is indeed heavily invested in Niger's uranium mining - but the lucrative Sahelian gold mining sector is actually dominated by Canadian, Russian, Australian and British companies.

Mr Macron has tried to change the tone of French relationships with Africa. But there is deep resentment and mistrust to be overcome and the choice of language is crucial. Striking that right note is never easy.

When he spoke at the funeral of Chad's late President Idriss Déby in April, Mr Macron's declaration of support for the country's stability and territorial integrity were widely interpreted as backing for the new junta headed by Déby's son Mahamat.

Yet in fact he had also called for inclusiveness, dialogue and a democratic transition - points that went much less remarked.

Paul Melly is a Consulting Fellow with the Africa Programme at Chatham House in London.