COP26: What African climate experts want you to know

- Published

Africa is the continent likely to bear the brunt of the effects of climate change even though studies show it has contributed least to the crisis.

So even though Africa has released relatively small amounts of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, external, those living on the continent are likely to be the victims of climate emergency disasters.

It is already suffering from extreme weather events and changes to rainfall patterns linked to climate change - leading to droughts and flooding. With a rapidly rising population, this has knock-on effects for food, poverty and gives rise to migration and conflict.

Here five climate experts tell the BBC's Dickens Olewe the issues world leaders need to remember as they hammer out solutions to rapid climate change at COP26.

'Africa's development is non-negotiable'

Dr Rose Mutiso, Kenyan - research director of Energy for Growth Hub:

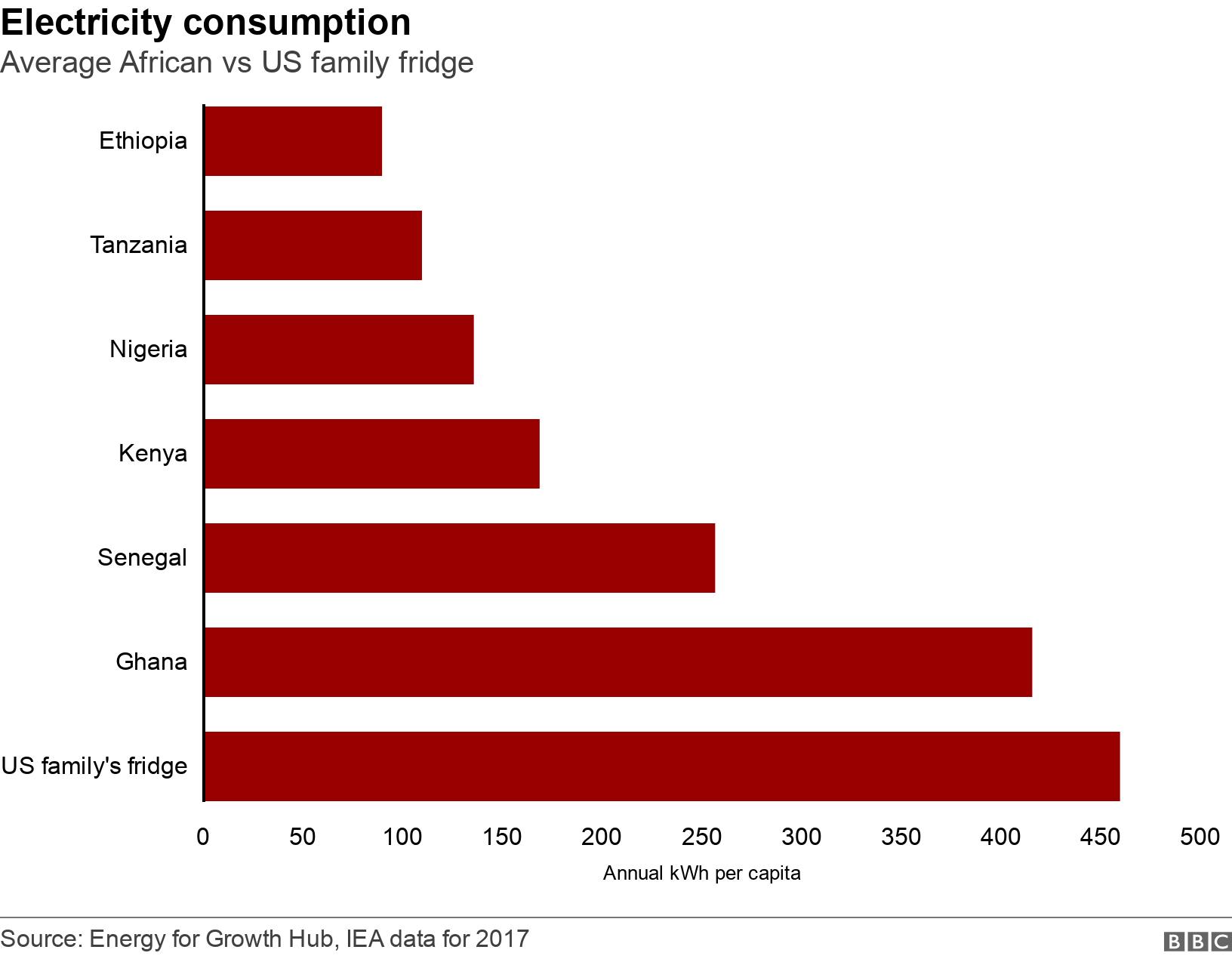

The average African uses less electricity each year than one refrigerator consumes in the US or Europe.

But this is going to grow - especially as temperatures rise - as Africans will have to have more energy to cool their homes and irrigate farms.

Africa too must be allowed to develop and build up its infrastructure - something that requires more energy.

So we must simultaneously have more power for rapid economic growth and quickly find alternatives to fossil fuels to provide this energy.

Yet African countries are being constrained by rich nations who make grand statements about their commitments while continuing to burn fossil fuels at home.

Kenya already generates a far greater share of its renewable power than the US or Europe.

While Africa welcomes partnerships, countries on the continent cannot sacrifice their ambitions. More thought needs to be given to what Africa needs in terms of industrialisation and creating jobs.

This means that richer nations need to actually reduce their own emissions and they need to live up to funding promises - in the past there have been pledges but little upfront money.

'Donors should not dictate'

Dr Youba Sokona, Malian - vice-chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change:

Climate change academics at African institutions are often not consulted by policymakers or governments on the continent.

Their research and potential solutions are shelved for too long and almost never enter into policy debates.

This fragmented approach also effects government policies. Different ministries will often be pursuing different donor-conceived ideas - with no systematic senior political co-ordination.

This leads to piecemeal solutions.

So donors should not dictate policy but work more closely with governments on a co-ordinated approach.

This is a chance for Africa to think creatively about how to develop and address climate change at the same time.

'Emissions need to rise first'

Prof Chukwumerije Okereke, Nigerian - climate governance and international development scholar:

Despite the large-scale and deep impact of climate change on Africa, the support countries are given to adjust is minimal.

Instead international partners focus on preventing or reducing the emission of greenhouse gases - three times more is spent on this.

The global consensus seems to be that all countries must quickly achieve a target of net zero - which means not adding to greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere, so any emissions are balanced out by removing greenhouse gasses via plants or new technologies.

This neglects the massive development and energy challenges Africa faces. Put bluntly, emissions from the continent may need to rise significantly in the near term before they fall.

Many rich countries seem to be expecting Africa to leapfrog to clean technologies for producing energy - but are not so keen to commit the scale of investment needed to make it happen, though the recent deal for South Africa to reduce its reliance on coal is a step in the right direction.

Fossil-fuel-rich African nations do need to know that the world is changing fast and create institutions and policies to drive a transition to green energy. There are great examples in Rwanda and Ethiopia. But much more needs to be done and poor governance remains a major barrier.

'Give grants not loans'

Dr Christopher Trisos, South African - African Climate and Development Initiative says:

Many countries in Africa already rely heavily on renewable energy - hydropower for electricity generation.

But recent droughts, such as El Niño of 2015-16, caused widespread electricity shortages.

Research shows future climate change could reduce hydropower capacity considerably in major African river basins - and hit the agricultural sector where many people are employed.

Droughts could affect Africa's hydroelectric dams

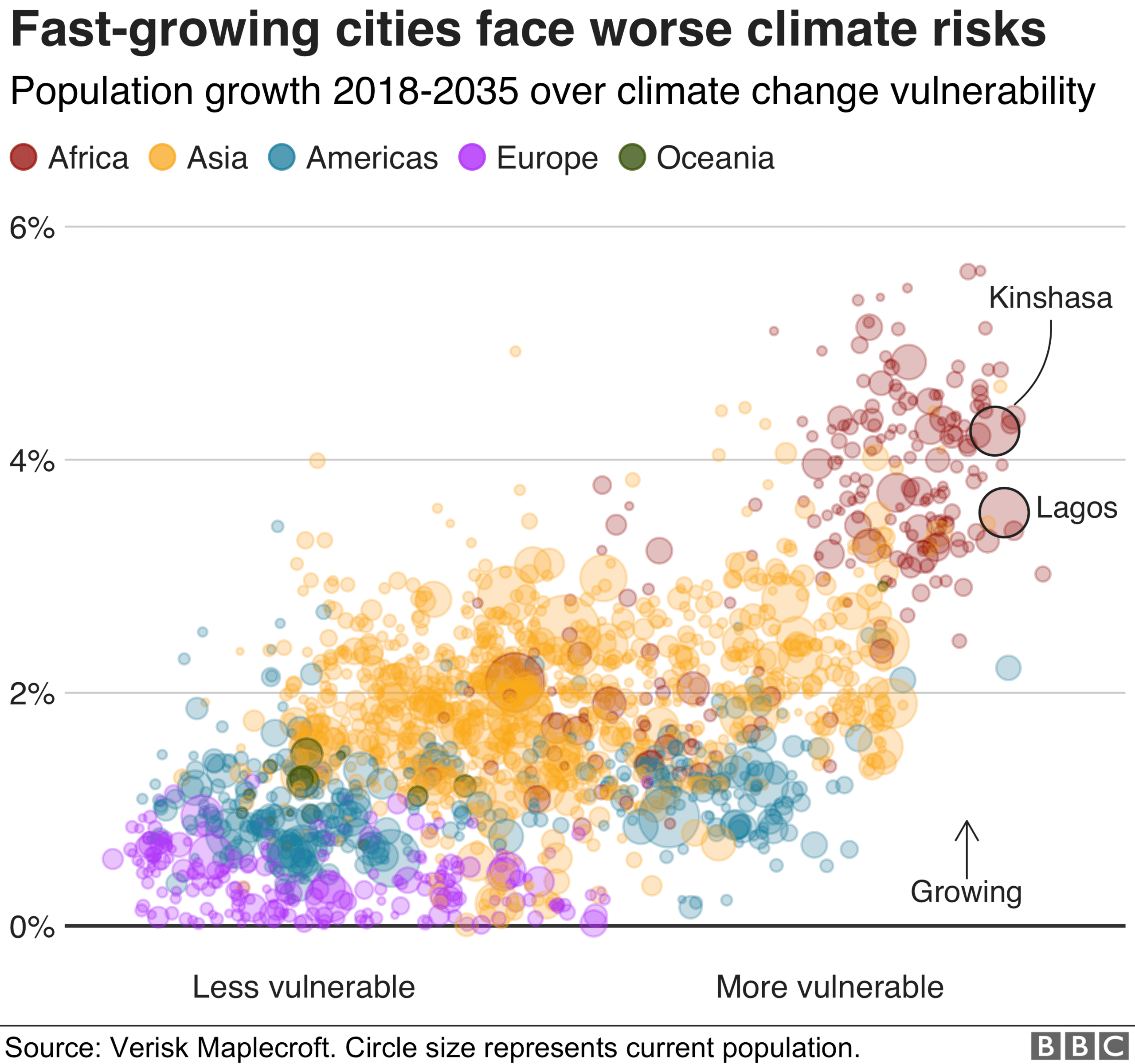

The combination of climate change and rapid urbanisation will have devastating effects.

Limiting global warming to 1.5°C would massively reduce future damage to African livelihoods, health, infrastructure, economies and ecosystems - the World Bank estimates climate change could push around 40 million more Africans into extreme poverty by 2030 if not addressed.

To achieve this requires deep emission cuts, especially from high-emitting countries outside Africa.

Yet investment to help African countries adapt to the changing weather, known as adaptation funding, is crucial.

Between 2014 and 2018 only 46% of what was committed by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries for adaptation in Africa was disbursed.

The quality of finance also matters as most of it is provided at the moment via loans rather than grants.

This means countries that have done little to cause the climate crisis are becoming further indebted to adapt to climate change.

African policymakers also need to adopt a government-wide approach so all sectors can become more climate resilient.

'Polluters must pay'

Dr Kgaugelo Chiloane, South African - founder of KEC Environmental Solutions says:

Vulnerable and poor African communities need help to adapt to the inevitable impact of climate change - but their voices must also be heard.

There is a lot of traditional knowledge and expertise on the ground that is ignored.

Policies are often implemented without the involvement of local communities and their buy-in.

A bottom-up approach in Africa needs to be part of a government's overall climate change policy.

And the "polluter pays principle" should be a key strategy for all governments.

Article Eight of the 2015 Paris Agreement recognises the importance of addressing the loss and damage associated with adverse effects of climate change, yet there hasn't been finance allocated for this.

Big carbon-emitting companies should be made to take responsibility and pay for the loss and damage they have caused as big polluters given they have generated profits for decades.

These comments have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Young climate activists from Africa share their message to world leaders