'People will starve' because of US aid cut to Sudan

The community kitchens, like this one photographed in December, have provided a vital lifeline for many

- Published

The freezing of US humanitarian assistance has forced the closure of almost 80% of the emergency food kitchens set up to help people left destitute by Sudan's civil war, the BBC has learned.

Aid volunteers said the impact of President Donald Trump's executive order halting contributions from the US government's development organisation (USAID) for 90 days meant more than 1,100 communal kitchens had shut.

It is estimated that nearly two million people struggling to survive have been affected.

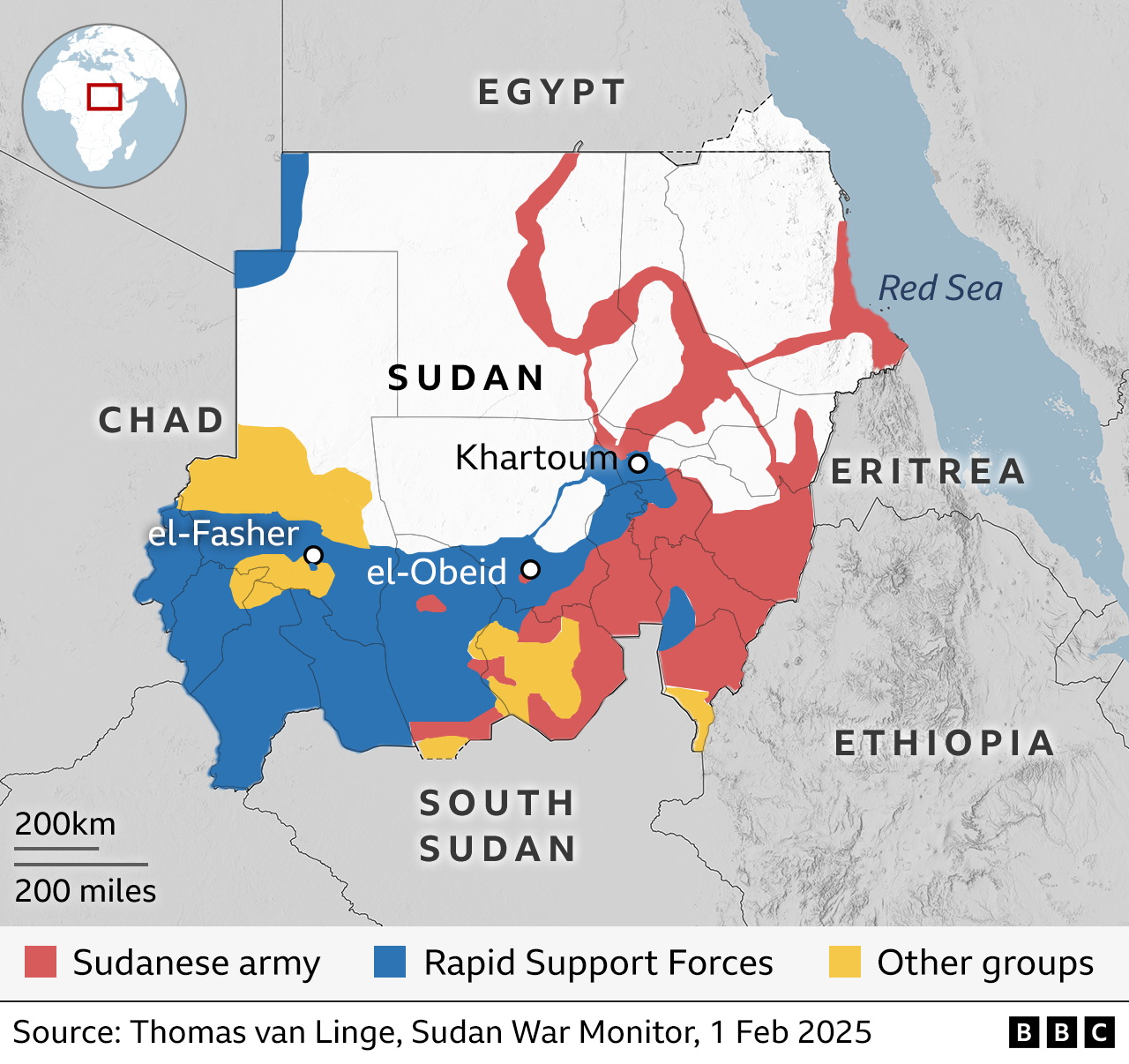

The conflict between the army and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has killed tens of thousands of people, forced millions from their homes and left many facing famine since it erupted in April 2023.

The kitchens are run by groups known as emergency response rooms, a grassroots network of activists who stayed on the frontlines to respond to the crises in their neighbourhoods.

"People are knocking on the volunteers' doors," says Duaa Tariq, one of the emergency room organisers. "People are screaming from hunger in the streets."

The Trump administration abruptly suspended all US aid last month to determine whether it was "serving US interests", and moved to begin dismantling USAID.

The State Department has issued an exemption for emergency food assistance, but Sudanese groups and others say there is significant confusion and uncertainty about what that means in practice.

The normal channels for processing a waiver through USAID no longer exist, and it is not clear if cash assistance - on which the communal kitchens depend - will be restored, or only goods in-kind. According to some estimates, USAID provided 70-80% of the total funding to these flexible cash programmes.

Parts of the capital, Khartoum, have been left in ruins by the fighting

The closure of the majority of Sudan's emergency kitchens is being seen as a significant setback by organisations working to tackle the world's largest hunger crisis, with famine conditions reported in at least five locations.

The network of communal feeding centres relied in the early stages of the country's civil war on community and diaspora donations but later became a focal point for funding from international agencies struggling to access the conflict zones, including USAID.

It is a "huge setback" says Andrea Tracy, a former USAID official who has set up a fund, the Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition, for private donations to the emergency rooms.

The former head of USAID, Samantha Power, had embraced the idea of working with the local groups rather than relying only on traditional channels like the UN.

Money had started to flow through international aid organisations that got US grants, but a channel for direct funding was in the works.

"It was ground-breaking," says Ms Tracy. "The only time that USAID had ever done this was with the White Helmets [humanitarian group] in Syria."

For Ms Tariq, the cut in US funding made it impossible to buy stock for the more than 25 kitchens in the six neighbourhoods in the capital, Khartoum, she helps to service. She told the BBC that left them unprepared for a worsening situation as the army advanced on the area, which has been held by the RSF since the conflict broke out.

There was widespread looting of markets as the RSF began to withdraw and the army tightened its siege.

Most of the kitchens had closed, she said. Some are trying to get food on credit from local fishermen and farmers, but very soon "we expect to see a lot of people starving".

Those behind the community kitchens are now hoping to fill the funding gap through private donations

Here and in the rest of the country, Ms Tracy's Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition fund will do what it can to plug the gap left by USAID.

"I think we can shore up [the emergency kitchens]," she said, "but the reality is that [private donations] are going to have to do even more now, because even if humanitarian assistance resumes, it's never going to be what it was."

"These volunteers were challenging us to work differently, and we were responding," says a member of a former USAID partner organisation.

They are "exhausted, traumatised and underfunded" and "we were scaling up to help them".

The State Department did not answer specific questions about waivers for Sudan, saying that information was shared directly with groups whose applications were successful.

"The aid review process is not about ending foreign aid, but restructuring assistance to ensure it makes the United States safer, stronger, and more prosperous," it said in response to a BBC query.

The UN World Food Programme (WFP) says it has received waivers for its 13 existing Sudanese grants with USAID, but there is no certainty about what comes next for future funding. That would anyway have been under negotiation - now the talks will take place in changed circumstances.

In 2024 the US was the largest single donor to Sudan, both in direct donations and in contributions to the UN's Sudan Humanitarian Response Plan.

Millions have been forced from their homes and some - like these people arriving in South Sudan - have fled to neighbouring countries

Top UN officials told the BBC the impact of Washington's policy shift would be felt beyond the borders of Sudan, with more than two million civilians now refugees in neighbouring countries.

"I witnessed people who have fled conflict but not hunger," said Rania Dagesh, the WFP's assistant executive director for partnerships and innovation, after visiting camps in Renk and Malakal, South Sudan, earlier this month.

The influx of refugees has only strained available meagre resources further.

"We have to rationalise, rationalise, rationalise," says Mamadou Dian Balde, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees' regional bureau director.

He had also been to visit refugee camps in Chad and Egypt when he spoke to the BBC. "We are strained. It's extremely difficult."

They both credit the local communities for welcoming those seeking refuge and sharing with them the little that is available. In the case of South Sudan, "it is a million extra people who've come in to a country where already 60% of the population is in emergency hunger", says Ms Dagesh.

Most families are now down to a meal a day, with children and the elderly given priority.

"But you see them wearing out and thinning in front of you - malnourished children. You see mothers who are trying to breastfeed, and there is nothing coming out of their breast," she said.

Most of the refugees are women, children and some elderly people.

They say most of the able-bodied men were either killed or simply disappeared. So, they fled to save themselves and the children. They have nothing.

Faced with the hunger in the camps, some in South Sudan have tried to sell firewood. But Ms Dagesh says it exposes them to harassment, violence and rape.

More than 700,000 Sudanese have headed west into neighbouring Chad since the war began

Many of the refugees she met had come from Sudan's agricultural areas. The war disrupted their lives and livelihoods.

They would want to see peace restored so they can go back home, but the fighting has been raging for close to two years now with no end in sight.

With the hunger situation deteriorating inside Sudan in the absence of a ceasefire, the closure of the kitchens supplying emergency meals will only increase the numbers fleeing across borders.

Yet aid agencies that normally would help are strained.

The UNHCR says it has been forced to rationalise "to levels where our interventions are absolutely limited - they are at the minimum".

It does not help that the agency was already underfunded.

The UNHCR's call for donor contributions last year yielded only 30% of the anticipated amount, forcing their teams to cut "everything", including the number of meals and amount of water refugees could receive.

The US has been the UNHCR's main funder and the announcement last month of the aid freeze and subsequent waiver appeared to have thrown things into limbo.

"We are still assessing, working with partners, to see the extent to which this is affecting our needs," Mr Balde told the BBC.

Faced with impossible choices, some refugees are already resorting to seek refuge in third countries, including in the Gulf, Europe and beyond. Some are embarking on "very dangerous journeys", he says.

More BBC stories on Sudan:

Go to BBCAfrica.com, external for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external