Ethiopia's war one year on: How to end the suffering

- Published

An emotional ceremony has been held to mark the first anniversary of the war

Tigray's rebel forces currently have the upper hand in the war that erupted a year ago in northern Ethiopia.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who fell out with the governing party of Tigray over his political reforms, has declared a nationwide state of emergency - it is fear and uncertainty that now rule.

As rebels advance towards the capital, the government has asked residents of Addis Ababa to mobilise and protect their neighbourhoods.

Fighters from Tigray, led by the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), took the cities of Dessie and Kombolcha over the weekend.

They are in the Amhara region, which neighbours Tigray, and are about 400km (250 miles) from the capital.

The battle for Dessie was believed to have been one of the most ferocious in the war as the city is seen as the gateway to Addis Ababa, in the south, and the border with Djibouti, in the east.

Food aid is distributed at a camp for people displaced by the fighting in Amhara

A man who worked at the main hospital in Dessie before it fell said the city had changed dramatically over the last few months as fighting raged in the region.

Asking not to be named, he told the BBC that Dessie was known as the "capital of love" because of its multi-ethnic and cultural mix - a thriving economic hub.

But in the last few months, thousands of people have poured in, fleeing the rebel advance.

"To and from work, small children would pull at my trouser legs and beg me for money to buy bread."

He and more than 10 of his colleagues abandoned the hospital when they saw government soldiers leaving the town.

He is now in Addis Ababa from where Tewodrose Hailemariam, a senior member of the National Movement of Amhara (NaMA), is mobilising communities to send fighters to stop the advance as well as distributing aid to those displaced.

He says his party believes the TPLF's real motivations are to come back to power.

The TPLF led the country for 27 years until 2018 - becoming sidelined by the government of Prime Minister Abiy.

"There are two options - either the TPLF is defeated and the Ethiopian central government is saved. Or the worst-case scenario is that the TPLF rules and controls Addis Ababa and then there will be civil war in the entire nation," Mr Tewodrose told the BBC.

Tigrayans 'being rounded up'

For Tigrayans in the capital, the fall of Dessie has ratcheted up ethnic tension in the city.

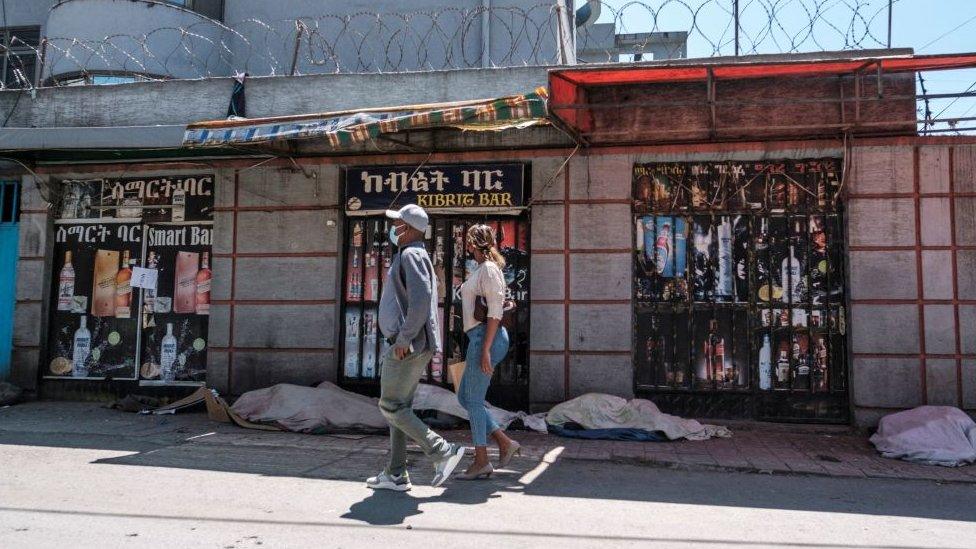

A Tigrayan lawyer who lives in Addis Ababa said it was no longer "the city where I was born and where I grew up". Police have been rounding up Tigrayans in raids on homes, cafes and bars - and even during identity checks in taxis and buses, she said.

In other cases this week, the BBC was told of a group who were picked up while having dinner at a restaurant.

Some shops and venues owned by Tigrayans in Addis Ababa have closed

"If you are Tigrayan you have no case. You are arrested. The arrest is in the name of ethnicity," one resident said.

Addis Ababa's police spokesman said arrests were only made after obtaining evidence of illegal activities. He confirmed that most of those arrested were Tigrayans, but said that members of other ethnic groups were also detained.

The rebels say their advance is to force the government to end a blockade on the northern region of Tigray, where aid is needed and power and banking services have been cut.

Since May, the United Nations has warned that 400,000 people are on the brink of famine there.

After the TPLF pushed the army out of Tigray's capital, Mekelle, in June, aid agencies say they have faced roadblocks on roads leading to the region, while restrictions on fuel and money have made it hard to bring in emergency relief to more than five million people in need.

After initially laying out a framework for negotiations with Mr Abiy's administration, the Tigrayan forces, emboldened by their military gains in the Amhara and Afar regions over the last few months, now say they will not talk.

Tsadkan Gebretensae, a former army general and senior commander of the Tigrayan forces, has said the war is almost over and the next step will be a post-Abiy national dialogue.

"We have never intended to resolve the country's political complexity on just our own terms. We will create a platform to bring all stakeholders together and discuss the future of the country," he told Tigrai Television.

Parents' shock

The humanitarian crisis in Tigray remains serious - as can be seen in videos from Mekelle's Ayder Referral Hospital where the cries of one-year-old Eden Gebretsadiq, linked up to a feeding tube, echo through the corridors.

Mebrhit Giday is 11 and her father says she has heart complications, probably caused by a lack of nutrition

"At first, I didn't know it was caused by a shortage of food. They have now told me she is malnourished," her shocked mother, Hiwote Berhe, says as she tries to comfort her.

"My husband used to be employed - while I took care of the children at home. We used to raise our children well. They used to get the best food and they were always well dressed."

In another bed is Mebrhit Giday, her limbs look painfully thin as her father, Gidey Meresa, gently sits her up to eat a banana.

He says they travelled more than 100km to get to the hospital from their rural town of Kola Tembien, which saw some of the heaviest fighting when government troops were in Tigray.

Many residents were forced to flee to the mountains. When they returned after the army and its allies were expelled, they found their homes burnt and their oxen and donkeys stolen.

"That all happened - and we accepted it. But my daughter got seriously sick - she was very healthy before," he says. Doctors have told him the 11-year-old has heart complications, probably caused by a lack of nutrition.

These are rare voices from Tigray - smuggled out by medical officials for the BBC.

The shutdown of telecommunication and internet services means the network is patchy and it is incredibly difficult to speak to people there. The BBC, like many media houses, has been blocked from accessing the region.

Failing threats

On a recent visit to Ethiopia, International Committee of the Red Cross President Peter Maurer was not able to go to conflict areas.

We will bury this enemy with our blood and bones and make the glory of Ethiopia high again"

"At the present moment we don't see the light at the end of the tunnel," he told the BBC.

"The earlier we find a political solution bringing us out of the conflict, the better it is - because let's not fool ourselves, even if the conflict stops tomorrow, we will still have hundreds of thousands of people displaced and enormous needs."

The US, UN and African Union have all been urging talks.

Threats of sanctions and even the US announcement that it would remove Ethiopia from a key trade agreement have failed to change the course of the conflict.

William Davison, senior analyst at the International Crisis Group, thinks it would be in the government's interest to offer concessions - ending constraints on access to aid and restoring vital services to Tigray.

"International actors should also call on the Tigray leadership to show maximum restraint, as not only do they need to give Prime Minster Abiy Ahmed a final chance to change course, but a quick attempt to march on Addis would probably lead to worsening violence and destabilisation for everyone," he told the BBC.

Yet Mr Abiy, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for finally ending the war with neighbouring Eritrea, does not appear in the mood for compromise.

As Ethiopia marked the one-year anniversary of the war, the 45-year-old leader continued to urge his countrymen to head to the front lines or back the war effort.

"We will bury this enemy with our blood and bones and make the glory of Ethiopia high again."

More on the Tigray crisis:

QUICK GUIDE: Ethiopia's Tigray war - and how it erupted

WATCH: Three reasons why the war is still going on

Three reasons why Ethiopia is still at war, a year since the conflict began