Cape Town's Day Zero: 'We are axing trees to save water'

- Published

Cutting down trees to save a city from drought might seem like an unlikely plan, but that is exactly what the South African city of Cape Town is doing, soon after it became the first global city to come close to running out of water.

It is three years since it edged dangerously towards what was described as "Day Zero" - the moment when some four million inhabitants would be left without water.

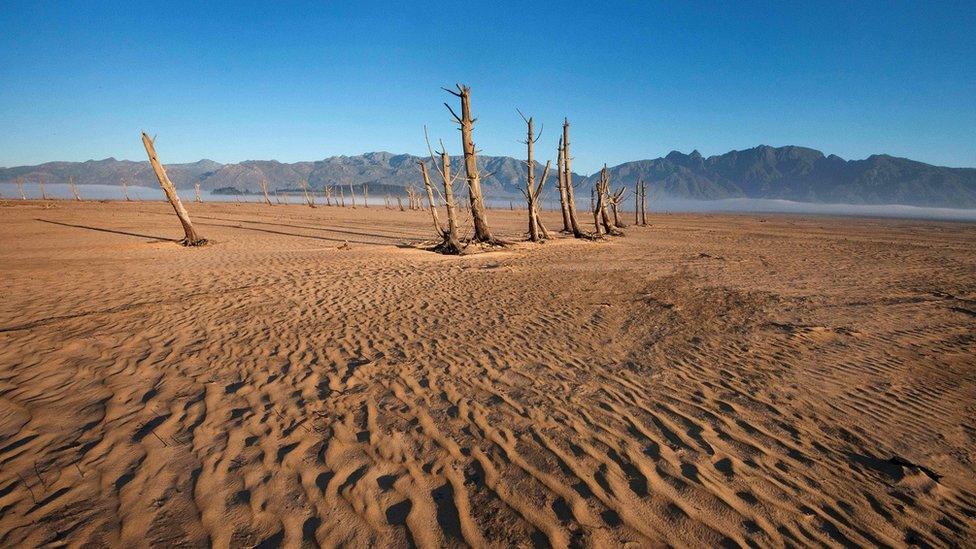

Its existential crisis was triggered by a severe and unanticipated drought that turned all the local reservoirs into dustbowls.

Today, dozens of teams armed with chainsaws are seeking to protect those reservoirs in an unusual manner - by chopping down tens of thousands of trees on the mountains surrounding them.

It is a furiously ambitious, and oddly counter-intuitive battle to limit the impact of climate change.

On a recent morning, high above a thick layer of mist, two workers abseiled down a steep ravine to remove several isolated pine trees in an area that was littered with stumps.

Non-native trees are responsible for using an equivalent of two to three months of Cape Town's annual water consumption

"The pines are not indigenous to this area. They use up so much water - much more water than indigenous plants. This is the green infrastructure that we need to fix," explained Nkosinathi Nama, who is co-ordinating the work for The Nature Conservancy on behalf of the Greater Cape Town Water Fund.

The non-indigenous pine trees, initially brought into the region for the timber industry, have spread fast across the mountains, crowding out the local, far more resilient, and less thirsty flora in Cape Town's catchment areas.

The pines, and other alien species like the eucalyptus, are now responsible for consuming an estimated 55 billion litres of water per year - equivalent to two to three months of the city's annual consumption.

"One of the lessons of Day Zero is that our water catchment areas need to be rehabilitated and restored so that they are resilient," he said.

'People got scared'

The initial five-year project is just one of many responses to Cape Town's 2018 water crisis, as scientists and administrators seek to learn from the experience.

As well as protecting and diversifying the city's water sources - including tapping into underground aquifers and installing desalination plants - experts have also been studying how humans responded to the threat of Day Zero in terms of water-usage.

Fear works… the city did quite well at preaching the message of saving water, and we halved our water use"

"We underestimate the ability of citizens to adapt to a crisis," said Dr Kevin Winter, an environmental expert at the University of Cape Town.

He points out that the city's water consumption nearly halved in the space of just three weeks in early 2018, from roughly 780 megalitres per day to under 550, before sinking even lower. An extraordinary display of public unity.

"People got really scared… And it had the desired effect," he said.

Siyabonga Myeza, a community activist working for the Environmental Monitoring Group in the Khayelitsha township outside Cape Town, agrees: "Fear works.

"That thought of running out of water as a city was quite tragic and very scary and the city did quite well at preaching the message of saving water, and we halved our water use.

"But in the long term we probably need a more holistic shift of mindset."

Halting irrigation

In the years since then, perhaps inevitably, water usage has increased in Cape Town.

But it remains far below the peak, set back in 2014, of 1.2 billion litres per day.

The experience of being forced to save water, or face fines or other penalties, has clearly left a lasting impression on many households.

Theewaterskloof Dam, the main supplier of drinking water to Cape Town, all but dried up in 2018 - today it is full

Other lessons include a greater appreciation of the role of agriculture in water management - in South Africa, as in many parts of the world, approximately 70% of water reserves are used to irrigate farmland.

Around Cape Town, farmers agreed to stop using municipal water completely for several months.

The Day Zero crisis also emphasised the increasingly unpredictable nature of weather patterns in an era of climate change.

By the end of 2018, Cape Town had received more rain than average. Just not during the usual seasons.

Seven-year drought

But while there is growing confidence that the Western Cape province is now in a much stronger position to cope with future droughts, there is little evidence that other parts of South Africa have learnt the same lessons.

They built us some toilets here, but we can't use them because there's no water"

In the far poorer Eastern Cape province, where farmers are struggling to cope with their own devastating seven-year-long drought, the heavily populated Nelson Mandela Bay area is facing acute water shortages that are widely blamed on years of mismanagement and corruption, and a failure to maintain vital water infrastructure.

"Fortunately, the leadership of Cape Town rose to the occasion. They did everything and… carried the people with them and as a consequence it helped them to overcome the problem," said Mkhuseli Jack, a businessman and opposition politician in the city of Gqeberha.

"Here it's the other way round because this place is led by very mediocre leaders. People have reached a stage where they won't believe anything politicians are saying here."

Gqerberha is now trying to focus minds by warning that its own Day Zero may arrive within months, while the taps have already run dry in some smaller towns in the province, and many neighbourhoods are dependent on irregular water truck deliveries made by a local charity.

"We've had no water for two days. I'm worried about the future because it's going to be worse and worse. Because [the government] doesn't look after us," said Elsie Hanse, 53, who lives in a shack in a township on the edge of Graaff-Reinet, a town in the Eastern Cape.

"They built us some toilets here, but we can't use them because there's no water."

Young climate activists from Africa share their message to world leaders