Somali survivor: The resilience of living through serial suicide attacks

- Published

Mohamed Moalimu worked as a BBC reporter in Somalia for years - and is now a government spokesman

Sunday's suicide bombing in Somalia's capital targeted a man who had survived four previous attacks. BBC World Service Africa editor Mary Harper considers why Mohamed Moalimu, who is now recovering in hospital, continues to brave a city wracked by violence.

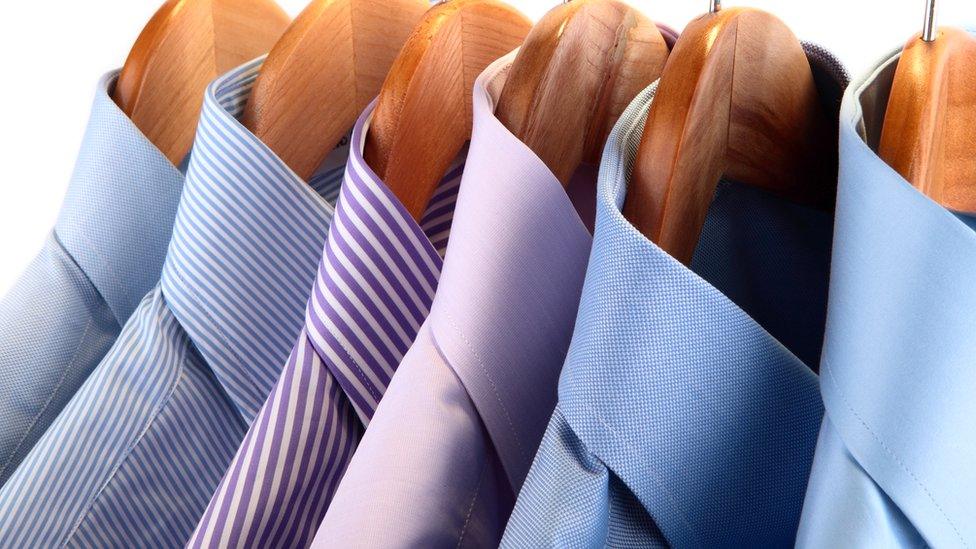

I have a list of essential information stored on my phone. Right near the top, above my passport number and bank account details, is the name Moalimu, the number 16.5 and the words "likes blue patterns and white".

These are the shirt size and preferred colours of my dear friend Mohamed Ibrahim Moalimu, who used to work as the BBC's reporter in Somalia.

Whenever I visit Mogadishu I buy shirts for Moalimu as a gift.

Moalimu likes blue and white patterned shirts

I love going to Jermyn Street in London, the Mecca for posh gentlemen's clothes. I sort through the dozens and dozens of colours, patterns and designs, looking for just the right thing.

In fact, I have two such shirts waiting in my suitcase for the next time I go to Somalia.

The problem is, Moalimu might not be there. He is in hospital in Turkey.

He was airlifted there in a little plane. It was not easy to manoeuvre his stretcher up and into the small space.

On Sunday, Moalimu was caught up in his fifth suicide attack. This time he was the direct target.

The attacker approached Moalimu's side of the car before blowing himself up

A suicide bomber ran towards his car and detonated the explosives when he reached the place where Moalimu was sitting.

There was little left of the attacker. The car was a mangled wreck.

I do not understand how Moalimu survived. He has a broken leg, chest wounds and other injuries but he is conscious and lucid.

Refuses to leave

If you were to meet Moalimu, probably the first thing you would notice is the terrible scars on his face. He got those in 2016 in his second suicide attack.

He was at his favourite seaside restaurant. Fighters from Islamist militant group al-Shabab stormed in from the beach, besieging the place for hours.

Moalimu has helped Mary Harper (L) navigate the complexities of the Somali conflict

Moalimu survived by lying in his own blood, pretending to be dead.

He told me how the militants kicked people's bodies to make sure they had died, shooting those who flinched.

It took months of treatment in Somalia, Kenya and the UK to heal him. The main fear was for his eyes.

It is difficult to relate the character of Moalimu to the dangerous world he lives in, and refuses to leave.

He is gentle, softly spoken and calm.

Mogadishu, and many of the people in it, are excitable, loud and nervy. Not surprising given that the city has been at war for more than three decades.

I was in Mogadishu shortly after Moalimu was caught up in his first suicide attack.

It was in June 2013 when al-Shabab smashed their way into a United Nations compound, spending about an hour inside killing as many people as they could.

Moalimu happened to be driving past when the militants struck. The remains of a suicide bomber landed on his car, smashing the windscreen.

In his usual polite, unassuming way, Moalimu showed me his windscreen, which was well-and-truly smashed up. He drew out a gruesome photo of his car in the aftermath of the attack.

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30 BST

He asked if I thought the BBC might pay for his windscreen to be repaired.

After all, he was working at the time. Reporting, as he so often did, on the violence in his hometown.

There is no way the BBC could cover Somalia the way it does without people like Moalimu.

He now works as a government spokesman, but when he was with the BBC, as well as filing his own reports, Moalimu was always ready to tell people like me exactly what was going on.

To this day, whenever I call him, he starts off with a list of exactly what has happened that day - the assassinations, the explosions, the political in-fighting.

He does this even when the purpose of my call is to ask him what kind of shirts I should bring him.

Unsung heroes of journalism

When Moalimu was my BBC colleague, he and one other person were the only ones I called before I went to Somalia.

If Moalimu said: "Don't come" - I didn't, even if it seemed to be relatively quiet. If Moalimu said: "Come" - I came, even if the security seemed a bit ropey.

I trusted Moalimu with my life. He was one of the unsung heroes of my profession.

I find it hard to understand why so much journalism gets attached to the name of one glorious, brave reporter, when there are often many others involved.

The producer, the camera-person, the sound-person and, perhaps most important of all, the "local" journalist, sometimes called "the fixer", who knows pretty much everything and upon whom the team almost entirely depends.

Moalimu was one such person, as are a number of other Somali journalists with whom I work and who also risk their lives every day.

I want to make a difference. I couldn't do that as a journalist. I need to work from inside the system"

After he left journalism I told Moalimu how disappointed I was when he became the government spokesman.

How could such a fair, honest journalist join "the other side"?

As always, his response was measured.

"I want to make a difference. I couldn't do that as a journalist. I need to work from inside the system. I want to be an MP and this is my first step towards that."

After he took on his new job, I had to develop a more formal relationship with him.

His shirts have also become more formal. They are stiff and white as he now needs to wear them with smart suits.

But whenever I walk down Jermyn Street, I will always think of the joy of choosing shirts for him, trying to match colours and patterns with his serene, gentle character.

More stories about Somalia by Mary Harper: