Was South Africa ignored over mild Omicron evidence?

- Published

South African hospitals were not as badly affected by the Omicron wave as by previous Covid-19 waves

South African scientists - praised internationally for first detecting the Omicron variant - have accused Western nations of ignoring early evidence that the new Covid variant was "dramatically" milder than those which drove previous waves of the pandemic.

Two of South Africa's most prominent coronavirus experts told the BBC that Western scepticism about their work could be construed as "racist," or, at least, a refusal "to believe the science because it came from Africa".

"It seems like high-income countries are much more able to absorb bad news that comes from countries like South Africa," said Prof Shabir Madhi, a vaccine expert at Johannesburg's University of the Witwatersrand.

"When we're providing good news, all of a sudden there's a whole lot of scepticism. I would call that racism."

Prof Salim Karim, former head of the South African government's Covid advisory committee and vice-president of the International Science Council agrees.

"We need to learn from each other. Our research is rigorous. Everyone was expecting the worst [about Omicron] and when they weren't seeing it, they were questioning whether our observations were sufficiently scientifically rigorous," he said, while acknowledging that the sheer number of new mutations in Omicron may have contributed to an abundance of scientific caution.

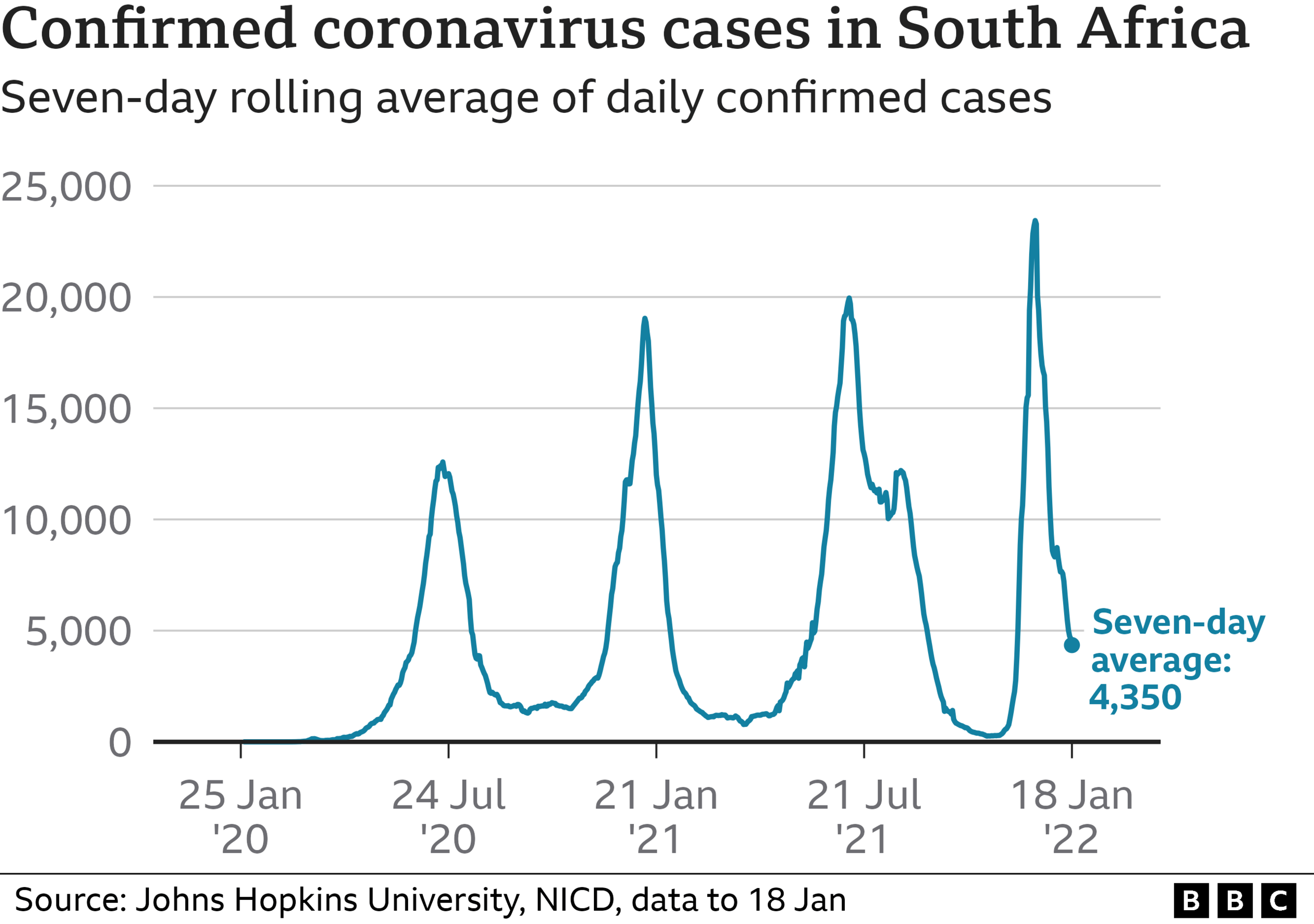

South Africa's latest wave of Covid, which began in late November 2021, is now declining as sharply as it once rose and is likely to be declared over, nationwide, in the coming days.

There are still concerns that the infection rate could spike again following the reopening of schools, but, overall, the country's Omicron wave is expected to last half as long as previous waves.

By early last month, scientists and doctors here were already sharing anecdotal evidence indicating that Omicron, while highly contagious, was resulting in far fewer hospital admissions or deaths than the Delta wave.

'Data met with scepticism'

"The predictions we made at the start of December still hold. Omicron was less severe. Dramatically. The virus is evolving to adapt to the human host, to become like a seasonal virus," said Prof Marta Nunes, senior researcher at the Vaccines and Infectious Diseases Analytics department of the University of Witwatersrand.

The WHO continues to warn against calling Omicron "mild," pointing out that its high transmissibility was causing a "tsunami" worldwide, threatening to overwhelm health systems.

But South African scientists are sticking by their data.

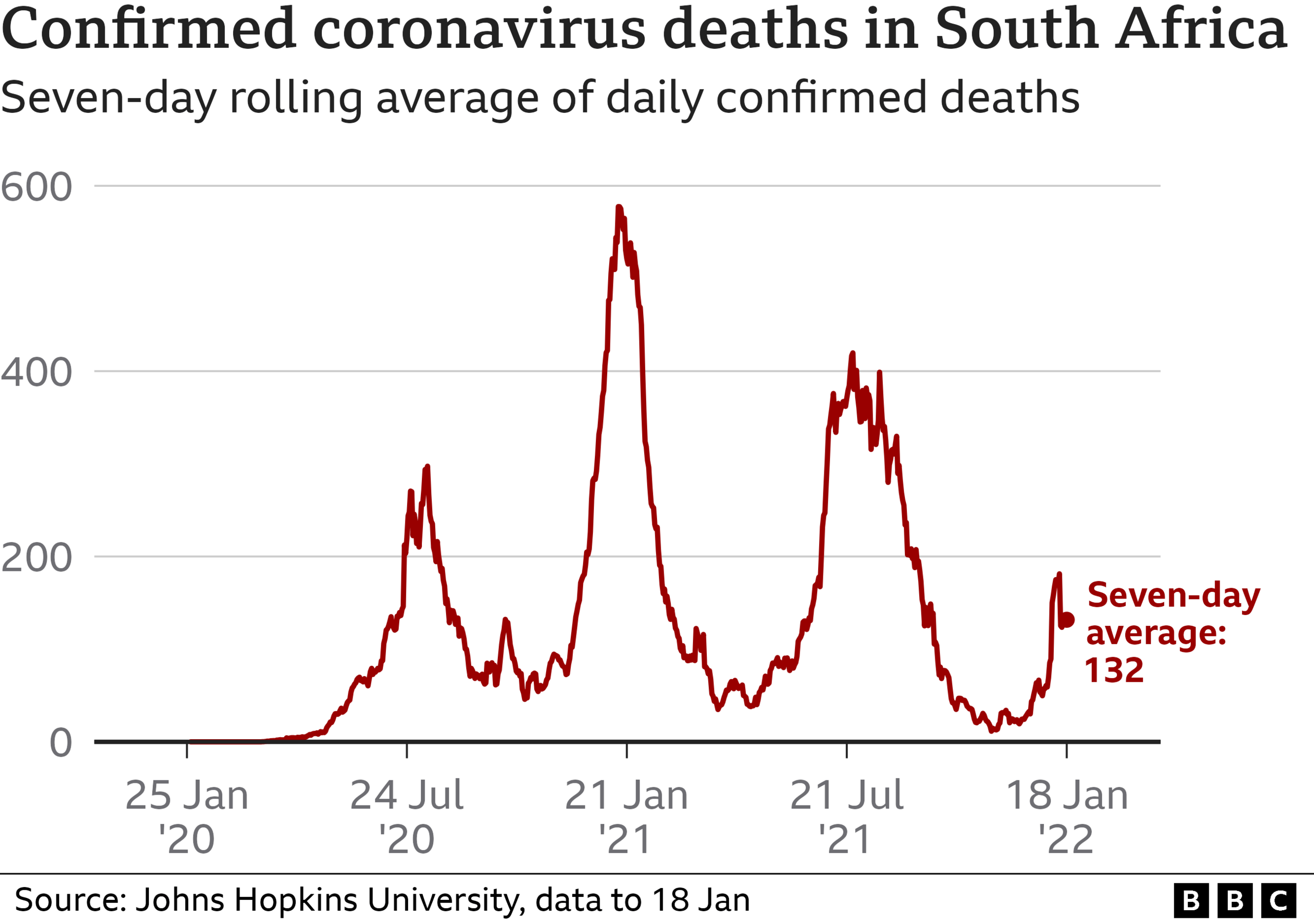

"The death rate is completely different [with Omicron]. We've seen a very low mortality rate," said Prof Karim, who pointed to the latest data showing hospital admissions were four times lower than with Delta, and the number of patients requiring ventilation was similarly reduced.

"It didn't take even two weeks before the first evidence started coming out that this is a much milder condition. And when we shared that with the world there was some scepticism," Prof Karim added.

It has been argued that Africa - or at least some parts of the continent - may be experiencing the pandemic differently due to demographics and other factors. South Africa's average age, for instance, is 17 years younger than the UK's.

But scientists in South Africa insist that any demographic advantage the population might have in terms of battling Covid is outweighed by poor health. Excess deaths in South Africa during the pandemic now sit at 290,000 - or 480 per 100,000 people - which is more than double the UK figure.

"The fact is that South Africa has got a much more susceptible population than the UK when it comes to severe disease. Yes, we've got a younger population… but we've got an unhealthier population because of a higher prevalence of other co-morbidities including obesity and HIV," said Prof Madhi.

"Each situation and each country has some unique characteristics. But we've learned how to extrapolate from one setting to another," said Prof Karim.

The figure of 290,000 excess deaths has not been confirmed as an accurate reflection of the pandemic's toll in South Africa. It is three times the number of official Covid-19 deaths.

But scientists here believe a majority of those excess deaths are probably due to the pandemic. Half of them occurred during the Delta wave, but, so far, only 3% transpired during the Omicron wave, said Prof Madhi.

No more quarantine

South Africa's government declined to introduce tighter restrictions during the Omicron wave and bitterly criticised foreign governments for their initial imposition of strict travel bans from the region.

Scientists here have generally welcomed the government's light-touch response, and now argue that other countries might do well to follow its example.

"We believe the virus is not going to be eradicated from the human population. We must now learn how to live with this virus and it will learn how to live with us," said Prof Nunes.

There is some concern that people will not now come forward for vaccines which have prevented severe disease

"The [low death rate from Omicron] shows we're in a different phase of the pandemic. I'd refer to it as a convalescent phase," said Prof Madhi.

He observed that South Africa had, "for all intents and purposes", stopped quarantining and contact tracing, and he urged the government to stop testing for Covid-19 at a community level too, saying it was unnecessary and amounted to pointless "bean counting".

Instead, he said the priority should be to minimise the number of people who are hospitalised by Covid-19.

Prof Madhi also expressed concern that mixed messages about South Africa's growing success in fighting the pandemic could "really diminish confidence in vaccines [despite the fact that] we know vaccines prevent severe disease".

Although South Africa lags far behind countries like the UK in terms of vaccination rates, at least three-quarters of the population now enjoys significant protection from a combination of prior infections and vaccinations.

Prof Karim acknowledged that Omicron's high transmissibility was causing temporary problems for countries like the US, but, citing South Africa's own experience, he said "the good thing is that because [the infection rate] has gone up that fast, it'll go down that fast too, so the pressure on hospitals will be much less".