Waking up to the war in Balochistan

- Published

Attitudes are hardening in Pakistan's restive Balochistan province against the government, but the state is now belatedly reaching out to the Baloch separatists. Writer Ahmed Rashid considers whether after years of civil war, talks could end the bloodshed.

It took an obscure United States congressman holding a controversial hearing in Washington on the civil war in Balochistan to awaken the conscience of the Pakistani government, military and public.

For years the civil war in Balochistan has either been forgotten by most Pakistanis or depicted as the forces of law and order battling Baloch tribesmen, who are described as "Indian agents".

Just a few weeks ago, Interior Minister Rehman Malik even hinted that Israel and the US were supporting the Baloch separatists, while the army had totally ''Indianised'' the Baloch problem.

On 23 February, Mr Malik did an about-face, saying that the government was withdrawing all cases against Baloch leaders living in exile and asking them to return home for talks. ''I will receive them in person,'' he told journalists.

Don't expect Baloch leaders to turn the other cheek at Mr Malik's sudden shift - the Baloch have seen too many such U-turns before.

Brahamdagh Bugti, head of the separatist Baloch Republican Party and living in exile in Geneva, remains sceptical.

His grandfather Sardar Akbar Bugti, the head of the Bugti tribe, was killed in 2006 on the orders of former President Pervez Musharraf in a massive aerial bombardment, while his sister Zamur Domki and her 12-year old daughter were gunned down in Karachi in broad daylight just in late January - allegedly by government agents.

He told journalists last week: ''I have seen this all before… I am not an optimist.'' Nevertheless, for the first time in years his face appeared on every Pakistani TV channel as he and other Baloch leaders gave interviews.

Broken promises

The civil war has left thousands dead - including non-Baloch settlers killed by Baloch militants - and has gone on for the past nine years, but it hardly made the news in Pakistan, let alone abroad.

The fifth Baloch insurgency against the Pakistani state began in 2003 with small guerrilla attacks by autonomy-seeking Baloch groups, who over the years have become increasingly militant and separatist in ideology.

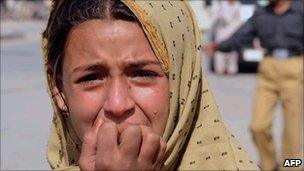

Blasts and ethnic violence have become a way of life in Balochistan province

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan reported that in 2011 there were 107 new cases of enforced disappearances. The so called ''missing'' are picked up, tortured, killed and their bodies left by the roadside in what the Baloch call ''a kill and dump policy'' by state intelligence agencies and the paramilitary Frontier Corps. Thousands of people have disappeared in the past nine years.

In a recent article for Dawn newspaper which generated intense public interest, external, novelist and satirist Mohammed Hanif described one incident in which a boy was picked up by government agents and went missing for two years before his body turned up.

US Congressman Dana Rohrabacher earned the wrath of the Pakistani establishment when he held a hearing on Balochistan and then introduced a non-binding resolution in Congress that Balochistan should be declared an independent territory.

The government is now calling for an All Parties Conference to discuss Baloch grievances, but Baloch leaders have already said they will not attend.

Community leaders like Brahamdagh Bugti and Harbayar Marri, a leader of the Balochistan Liberation Army who is in exile in London, have seen two major efforts by Pakistani politicians to talk to them fail in the past nine years - largely due to the army's intransigence.

The first was under former President Musharraf when some of his federal ministers tried to hold talks with the Marri and Bugti leaders. They were thwarted by Gen Musharraf who was determined to deal with the issue militarily, taunting the Baloch with quips such as ''this time you won't even know what hit you".

The second was when the present Pakistan People's Party government was elected to power in 2008 and President Asif Ali Zardari asked for a ceasefire in Balochistan for six months - which surprisingly was adhered to - and promised negotiations with Baloch leaders. However, the army was against any talks and the government's will to carry them out melted away.

Writing on the wall

Since then, there has been a hardening of the Baloch attitude and a widening and deepening of the revolt. Baloch leaders now openly talk of accepting aid from India and the US if it was available and separating from Pakistan to form a new country - which is anathema to most Pakistanis.

None of the earlier four revolts have received such support from all sections of Baloch society, including the educated middle class. The Baloch diaspora in Europe and the US is especially active.

Baloch nationalism is on the rise

Although Balochistan is the largest province in Pakistan, the Baloch number only five million people and are outnumbered in their own province by Pashtun tribesmen and other non-Baloch settlers like the Shia Hazaras who arrived in the 19th Century. What also irks the Baloch is that Pakistan allows the Afghan Taliban - who are Pashtun - to run their war against US forces in Afghanistan from Quetta, the provincial capital. The Taliban leadership council is called the Quetta Shura. Pakistan's authorities deny the claims.

Until now, there has been a kind of ethnic peace between the Baloch and Pakistani and Afghan Pashtuns living in Balochistan, but that could end in a bloodbath. Some right-wing American politicians like Dana Rohrabacher talk of an alliance between Baloch separatists and Afghanistan's anti-Taliban former Northern Alliance.

Such an alliance would jointly take on the Taliban. That is dangerous talk because it could end up with the partitioning of both Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The Pakistan army needs to see the writing on the wall and swiftly urge the government to open genuine talks and offer real concessions to the Baloch. The Baloch say they are beyond accepting any compromise with the state, but no Pakistani entity has ever tried talking to them.

Ahmed Rashid's book, Taliban, was updated and reissued recently on the 10th anniversary of its publication. His latest book is Descent into Chaos - The US and the Disaster in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia.

- Published1 February 2012

- Published3 January 2012