Theatre leads battle to save Macau's 'sweet speech'

- Published

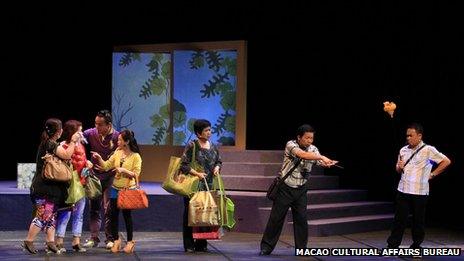

Performances in Patua may keep the language from dying out

In a dark basement theatre, Nair Cardoso runs through her lines before a rehearsal of a play that will be watched by hundreds of people in just a couple of weeks.

However, her character - Benina - speaks a language she only half understands. It is a problem shared by most of her fellow cast, not to mention her future audience.

The script is in Patuá - a creole that mixes Portuguese, Cantonese and Malay - that today is only spoken by a handful of Macau's residents and has been listed by Unesco as "critically endangered".

Patuá was once spoken by many Macanese - the Eurasians who acted as the Portuguese colony's administrators and interpreters and who today are trying to hold onto a distinct cultural identity in the predominantly Chinese city.

Ms Cardoso is part of a younger generation taking an interest in Macau's unique heritage

"It's part of us. It keeps us connected to our ancestors and our roots," says Ms Cardoso, a 33-year old Portuguese and Cantonese speaker who joined the theatre troupe two years ago.

She remembers her uncles speaking in Patuá but learnt the language during rehearsals from the play's writer and director Miguel Senna Fernandes, an energetic lawyer who has spearheaded efforts to preserve and revive the language.

His theatre company is called " Dóci Papiaçám de Macau" or "Macau's sweet speech" after the local name for the language.

Language of laughter

Mr Fernandes's own fascination with the language was triggered as boy, when he would watch his grandmother chatting with her friends.

"They were a bunch of old ladies and they would talk and they would laugh, laugh, laugh and laugh and I wondered what they were laughing about and why they were laughing so hard."

But aware that Patuá was frowned upon by Macau's Portuguese rulers, Mr Fernandes' grandmother was reluctant to translate, instead exhorting him to learn Portuguese.

"Because of this kind of thinking we really just tossed out a very interesting language," he says.

Mr Fernandes eventually mastered Patuá and revived an old custom of staging plays in the language. and has been writing and directing performances for the past 19 years.

Malay links

Mario Pinharanda Nunes, a specialist in Portuguese-based creoles at the University of Macau, says Patuá dates back to the 16th Century when the first Portuguese traders arrived in Macau.

They came from Malacca in Malaysia where a related creole - Papia Kristang - is still spoken by a small number of people, he says.

Mr Fernandes has spearheaded efforts to preserve and revive the language

The language evolved as Portuguese mixed with the local Chinese population. Unlike the British colonisers in nearby Hong Kong, the Portuguese frequently married local women, who converted to Catholicism.

As public education became more widespread, Patua became a language of the home rather than the workplace, and its decline began to accelerate in the early years of the 20th Century when Lisbon adopted a policy pushing the proper use of Portuguese in its colonies.

"That's when the community really started putting the creole aside and learning Portuguese," Mr Nunes says.

The language's foundation is Portuguese, although there are no rolled Rs. The grammar and syntax are closer to Cantonese: words are repeated for emphasis and verbs are not conjugated.

Mr Fernandes says that one of his favourite words is <italic>boniteza</italic> - an archaic Portuguese word for beauty.

Another word, <italic>min chi</italic>, reflects the arrival of the British in Hong Kong. A dish of minced meat, eggs and rice, it derives from a Cantonese pronunciation of the English word mince.

Survival?

Unesco's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger says there were 50 speakers of the language left in 2000. Mr Nunes believes that number may be in the hundreds if the Macanese diaspora in the US, Canada, Brazil and Australia are included.

However, unlike Malacca's Portuguese-based creole, Patuá is no longer passed from one generation to the next.

"I think revitalisation might be a step too far. It's hard to imagine that it could be a mother tongue again," he says of Patuá's chances of survival.

"But it could be learnt at a basic level for heritage purposes."

The Macau government designated Patuá part of the territory's "intangible cultural heritage" earlier this year.

And with the help of Mr Fernandes, researchers at Macau university have completed a Patuá dictionary and are working on a grammar as they scramble to document the language before the last native speakers die out.

Empty seats

This year's Patuá performance took ghosts as its theme and is called "Aqui Tem Diabo", which Mr Fernandes has translated into English as Spooky Doo.

It is not known exactly how many Patua speaker are left, but estimates range from 50 to hundreds.

It's a series of vignettes that take a lighthearted look at modern day life in Macau and poke fun at the foibles of the Macanese - such as the devoted Catholic lady who consults a feng shui expert on the location of her husband's grave.

Another sketch that drew much laughter lambasted the manners of hoards of Chinese tourists who come to the city to gamble.

For retired teacher Maria João Rangel and her daughter Sofia, Macanese who now live in Portugal, it was an enjoyable night out:

"Every year we come back and I think it's great that they are trying to keep the old traditions alive," says Maria.

The performance includes sketches in Cantonese to appeal to a broader audience and is subtitled in Portuguese, English and Chinese.

But with just 8,000 out of Macau's population of half a million identifying themselves as of Portuguese descent the audience is limited, as the dozens of empty seats testified.

Mr Fernandes, however, is optimistic. He is encouraged by the number of younger people who are joining his theatre group - eager to discover their roots as Macau changes fast under Chinese rule.

"The plays have triggered some long-forgotten memories and raised awareness of something quite ancient that is worth reviving," he says.

And in doing that, they may just have kept Patuá off its deathbed.