Ageing China: Changes and challenges

Continue reading the main story

Fewer children

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the government advocated a "later, longer, fewer" lifestyle, encouraging people to marry later, have wide gaps between children and fewer children overall. It also instated the controversial one-child policy. These were attempts to curb population growth in a bid to help modernise the economy.

Chinese women are having fewer children, but having a smaller generation follow a boom generation - and longer life expectancies - means that by 2050, it is expected that for every 100 people aged 20-64, there will be 45 people aged over 65, compared with about 15 today.

Use the slider below the graphs to see how China's age structure is changing

- 1950

- 1960

- 1970

- 1980

- 1990

- 2000

- 2010

- 2020

- 2030

- 2040

- 2050

- 2060

- 2070

- 2080

- 2090

- 2100

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2010)

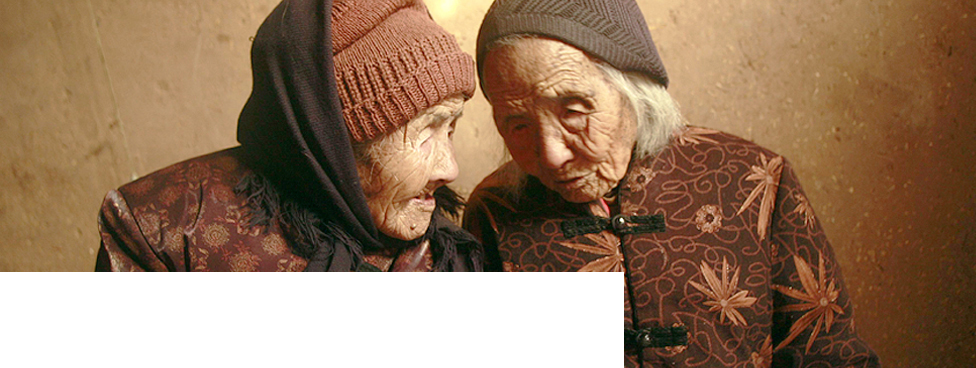

The 4-2-1 family

Only children from single-child parents face what is known as the 4-2-1 phenomenon: when the child reaches working age, he or she could have to care for two parents and four grandparents in retirement. One-child couple Zini and Lin are in that situation, and their family are concerned.

- 1950

- China was a developing country, with high birth rates and a life expectancy of about 44 years.

- 1980

- China's one-child policy was introduced in 1979. Exemptions are allowed, eg. couples who had a girl first, families in rural areas, etc.

- 2010

- When children of the one-child generation reach their 30s or 40s, there is a good chance their parents and grandparents will be alive and need some form of care.

One-child success?

China's fertility rate - the average number of children a woman has in their lifetime - is 1.6, which is lower than the rate in the UK and the US.

The Chinese government believes the one-child policy curtailed population growth, and that it prevented 400 million extra births.

The BBC asked Cai Yong, a population expert at the University of North Carolina, to estimate what the country's population growth would have been without the one-child policy.

His findings suggest that China's fertility would have declined at a similar rate without the one-child policy and would continue to decline even if the policy was discarded.

How did the one-child policy affect population levels?

Cai Yong writes:

The UN's Population Division and statisticians from the University of Washington developed a set of sophisticated models to predict a country's future fertility based on its fertility change history and fertility trends in all other countries.

Applying the same model to China, assuming we only know its fertility history prior to the one-child policy, we can "predict" China's fertility level since. The "predictions" can then be compared with what really happened.

China had a remarkable success in fertility reduction in the 1970s, before the introduction of the one-child policy: China's fertility dropped from 5.8 children per woman in 1970 to 2.7 in 1978. The model suggests that fertility would have continued its decline without the one-child policy, and possibly would have declined even faster.

This last point seems to be counterintuitive, but one explanation could be that the policy caused anxiety among the population, which prompted many to have children at an earlier time. There was a decline in age at first marriage and age at first childbearing in the 1980s.

Many exemptions to the one-child policy are made depending on location, job and the sex of your first child. Families who are not subject to any exemption can, if they can afford it, pay the fine for breaking the one-child rule and have more children. However, the policy took a toll on many families.

Critics point to the measures taken to ensure its implementation, including forced abortions, sterilisations and sex-selective abortions, which have skewed China's sex ratios; the latest census figures suggested nearly six boys were born to every five girls. Fertility decline is a global phenomenon: most developing countries experience fertility reduction without any draconian governmental measures.

Produced by: Dominic Bailey, Mick Ruddy, Marina Shchukina

~RS~q~RS~~RS~z~RS~23~RS~)

First arrests in India nun rape case

First arrests in India nun rape case