Resources at heart of Taiwan-Philippines maritime row

- Published

The Taiwan-Philippine row led to economic measures and military exercises

For generations, Quirino Gabotero Jr's family and the estimated 15,000 people in the Philippines' northernmost Batanes Islands have been relying on the sea for a living. But in recent decades, they have seen their food source decline.

The same body of water around the islands is also claimed by neighbouring Taiwan as its exclusive economic zone. Taiwanese fishermen are able to catch more fish with their bigger boats and more sophisticated fishing methods.

They have even depleted the stock of flying fish - something they use as bait, but is staple food for Batanes residents, said Mr Gabotero.

"During the times when we don't see them, we get 1,000 or 2,000 flying fish in one catch. When they're around, we don't catch so many, perhaps only 100," said Mr Gabotero.

Unlike Taiwanese fishermen, many of the Philippines 1.6 million fisher folk are not commercial fishermen, and nearly half of them are considered poor, according to the government.

"Our fishermen catch just enough to feed their family, but nothing more. They can barely build their house, or send their children to school. Some of them are so poor they have to work as migrant workers on the Taiwanese fishing boats to fish in their own waters," said Mr Gabotero.

Tensions over this unequal ability to tap the rich marine resources of the South China Sea have been brewing for years.

They exploded in a diplomatic row between Taiwan and the Philippines this month when 65-year-old Taiwanese fisherman Hung Shih-cheng was shot dead after Philippines coast guard opened fire on his boat while he was fishing in the overlapping waters of the two sides' exclusive economic zones.

Since then, both Taipei and Manila have sent naval vessels to disputed parts of the South China Sea.

This incident highlights how unresolved disputes in the resource-rich South China Sea could potentially threaten good relations among countries in the region, and even regional stability.

'No shelter'

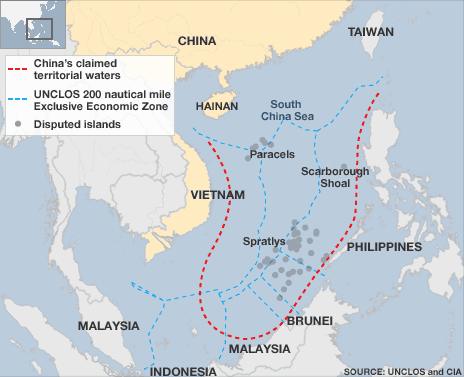

Besides Taiwan and the Philippines, several countries, including China, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei claim part or all of the sea - believed to be rich in oil and natural gas deposits, besides fish stocks.

While attention has been focused on the Philippines-Taiwan dispute, other countries are also involved in fishing and territorial disputes in the sea. Taiwan's boats also have been detained by Indonesia and Vietnam, while the Philippines regularly deal with "poachers" from China, Malaysia and Vietnam.

"The most problematic is China, not really Taiwan, because they have made a map which includes our territorial waters," said Jonathan Bickson, chief of the captured fisheries division in the Philippines' Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources.

"One country even sends maritime patrol vessels. When our fishermen go to these fishing grounds, they even drive them away, even though these are our fishing grounds, especially Scarborough Shoal in western Philippines," he said.

"So our fishermen now cannot even make shelter in Scarborough when there's rough seas or when there are typhoons. The situation has gotten worse in recent years."

China insists the shoal is historically Chinese territory.

In the case of the body of water separating Taiwan and the Philippines, Philippine fishermen have been notifying their coast guard when they spot Taiwanese boats. That has led to a rise in fines and arrests of Taiwanese fishermen.

Taiwan's Fisheries Agency estimates that in the past three decades, there have been 108 incidents of Taiwan's fishing boats being stopped, fined or confiscated or crews detained for six months to a year by Filipino authorities.

Fines imposed on the crews have ranged from $50,000 (£33,000) to $60,000, according to the agency. The actual numbers are believed to be higher because some cases are settled without being reported to Taiwan's authorities.

'Don't dare to sleep'

Taiwanese fishermen also see themselves as victims. For generations, they have lived off the sea, but they say each time they head out to what they consider as their fishing grounds, they face risks.

"The Philippines consider the area their waters, so they've confiscated our boats, fined us and they've opened fire in the past. This was not the first time. It's happened many times before," said Tsai Bao-hsin, director of Taiwan's Liouciou District Fisheries Association, whose fishermen regularly fish in the area.

Mr Hung was shot in waters both Taipei and Manila claim

At least one other Taiwanese fisherman was shot dead a few years ago. More than 1,000 boats have been confiscated, according to Mr Tsai.

When confronted, many of the fishermen have to make the split-second decision of whether to stop and pay a huge fine, risk having their boat confiscated and being jailed, or try to get away.

Investigators from both sides are probing the shooting of Mr Hung, but his son - who was onboard at the time - has said the boat was sprayed with bullets when they tried to get away to avoid paying a fine they didn't think they should pay because they were fishing in waters Taiwan considers its territory.

Despite the dangers, more than half of Taiwan's estimated 350,000 fishermen sail to the South China Sea. That's because it's a good place to catch the very valuable tuna - of which Taiwan is one of the biggest producers in the world.

But the killing of Mr Hung is considered by the Taiwanese as the last straw. Taiwan's fishermen are demanding their government negotiate an agreement with the Philippines on fishing rights to stop the harassment they say they regularly face and to prevent similar incidents from happening again.

"Sometimes we don't even dare to sleep at night when we are out at sea," said Hung Sheng-huei, who had fished since the age of 16 but gave it up after he was arrested by the Philippines in 2010 and spent three months in a crowded jail cell.

"When they stopped us at sea, they all had guns. They demanded I pay $120,000. It's like we were an ATM machine. I offered to wire them the money, but they wanted cash. I didn't have it."

Mr Hung said he ended up turning over his boat to them to get out of jail. He now works odd jobs for other fishermen and lives on his savings.

"It's a big impact on my family. We depend on the sea for a living," said Mr Hung, who added that he will only return to sea if the two sides reach a fishing agreement.

But most Batanes fishermen are opposed to the signing of such an agreement, even though Manila has expressed interest in holding talks at some point.

"We believe the Batanes territory, including the waters within it from the north to south, the Philippine government owns that," Mr Gabotero said. "We are against signing a fisheries agreement because that means we are giving our resources to them without getting our fair share."

It remains to be seen whether the two sides can find a mutually beneficial and acceptable way of resolving this difficult dispute. If they do, it could set an example for other countries with claims to these waters.

- Published27 May 2013

- Published16 May 2013

- Published15 May 2013

- Published10 May 2013

- Published7 July 2023

- Published15 January 2013

- Published9 February 2012