Pakistan quake highlights Balochistan ethnic fractures

- Published

Villagers in Teertaj turned away soldiers when they arrived after the quake with tents and food supplies

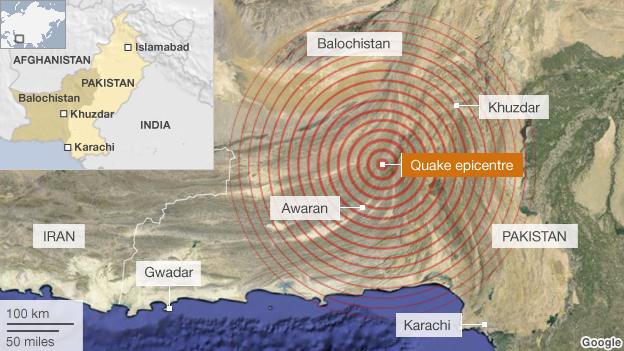

A powerful earthquake in Pakistan's south-western province of Balochistan killed 400 people and affected more than 300,000 last Tuesday.

A week on, the disaster - and the Pakistani government's response to it - have exposed the deep ethnic fault-lines threatening the stability of this nuclear-armed country.

Half an hour's drive on a dirt track outside the town of Awaran lies the village of Teertaj. Last week, when the area was struck by a 7.7 magnitude earthquake, 95% of the mud brick houses in the village collapsed.

Twenty-two people died in that small village alone.

Many of those who survived were deeply traumatised and suffered fractures - broken arms, ribs and head injuries. The main hospital in Awaran did not have an X-ray machine. Those who could manage to do so rushed their injured relatives to hospitals in the port city of Karachi - between six and seven hours' drive away.

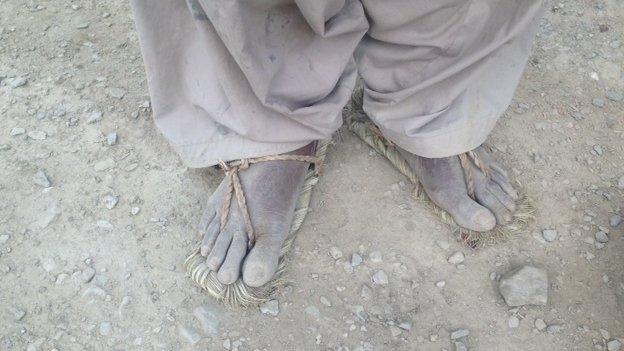

Within the next 48 hours or so, when Pakistani soldiers arrived in Teertaj with a truckload of tents and food supplies, the villagers turned them away. "We told them we did not want anything to do them," says a villager.

Insurgency

Resentment against the army and the official paramilitary force, the Frontier Corps, is not limited to a few villages. It runs deep in Balochistan, Pakistan's largest province in terms of area, rich in resources, but also its most impoverished region.

Thousands of Pakistani soldiers have been deployed there, and effectively control large parts of the province. The army says it is fighting for the territorial integrity of Pakistan. It is battling separatist Baloch insurgents, who they allege are being backed by foreign forces, namely India.

But the army itself is viewed as an outsider force, as it is largely composed of ethnic Punjabis and Pashtuns. The troops are accused of carrying out large-scale enforced disappearances and custodial deaths of Baloch nationalists - charges they deny.

Since the quake, army reinforcements have been brought in from the provincial capital, Quetta, as well as Karachi.

Balochistan is Pakistan's largest province in terms of area

Some army officials says force is sometimes necessary to establish the writ of the state

Balochistan is rich in resources but remains Pakistan's most impoverished region

"There is not a village in this area which has not experienced abuses by the Pakistani army. Several of my friends and colleagues have been caught and killed in cold blood; some remain missing to this day," says 29-year old Baloch Khan, head of one of several Baloch nationalist groups, the Baloch Student Organisation (Azad).

He was a student of history at a university in Karachi, but abandoned higher education and took to the mountains of Balochistan. The faction of Baloch nationalists he now leads is outlawed by the authorities and described as an anti-Pakistan militant group.

Today, like the rest of his comrades, Baloch Khan is on the run from the Pakistani security agencies. "If they find me, they will kill me," he says.

We met him at a secret location in the middle of nowhere in Awaran district. He sat there in front of a straw hut surrounded by a couple of mud-brick houses. For someone opposing the mighty Pakistani army, he appeared surprisingly calm and at ease with his surroundings.

"This is my homeland, which has been occupied by the Pakistani army. We are fighting for a free Balochistan," he says.

Are you a militant? Do you carry weapons for your protection, I asked.

"No," he says. "I carry books with me. I like to read about people like Ho Chi Minh and Che Guevara."

But surely, these are desperate times, when survivors of earthquake need tents, medical supplies and doctors?

I asked him, why disrupt the relief effort?

"Our people are desperate for help, but how can we take aid from the same people who have destroyed our homes, killed our people and subjugated us for decades?" he asks.

Troop build-up

Baloch nationalists fear the army is using the calamity in Awaran to deploy more troops and prepare for a fresh military operation against the insurgents.

Army officials admit that since the earthquake, their base in Awaran has expanded, with reinforcements being flown in and trucked in from the provincial capital, Quetta, as well as Karachi.

But they say the deployment is to safeguard the relief operation.

"Our rescue and relief teams have been fired upon. Our helicopters have been attacked," says Maj Gen Mohammed Samrez Salik, general officer commanding of 33 Infantry Division. "They are trying to hamper our relief activities. But we are fighting back."

He recognises that the army faces resentment from some of the disaster-hit villages, but insists the mood is shifting.

"People can see we are trying to help them. They can see we are on their side. And [given] the kind of respect I am getting when I visit some of these villages, I have no reason to believe we are viewed as an occupation force."

Privately, other army officials say that the force sometimes has to do what needs to be done to establish the writ of the state.

One official said: "If one of their guys has killed several of my men, what treatment do you expect me to give him when we catch him?"

- Published25 September 2013

- Published25 September 2013

- Published27 September 2013

- Published28 September 2013