Woman engineer at the centre of India's space mission

- Published

Meet one of the space scientists working on the Mars mission

For two years, Minal Sampath, a systems engineer working on India's mission to Mars, worked flat out in a windowless room, often for 18 hours a day, to be ready for the country's most ambitious space project to date.

"We had a great team and there [was] an understanding between us that we [had] to get the work done to meet the deadline," she says. "The launch date [was] fixed and we could not miss it."

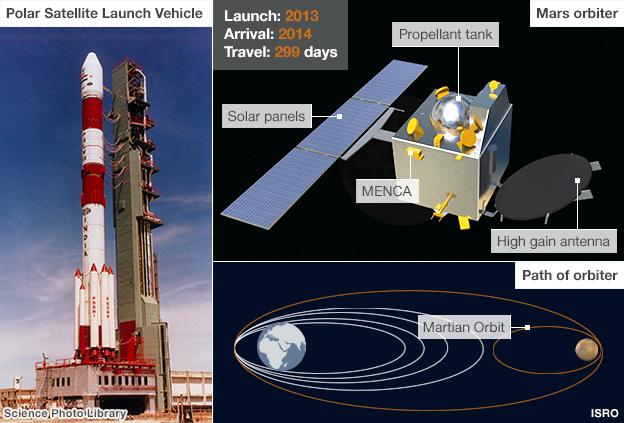

That day finally came on 5 November last year when the Mars Orbiter Mission took off at 09:08 GMT from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre on the east coast of India.

It also marked the moment that India joined the short list of nations capable of launching such a mission.

Only the Soviet Union, Russia, the US, Britain, Europe, Japan and China have done so. Of the 40 missions launched so far, fewer than half have been successful.

Team of 500 scientists

If the Indian Mars Orbiter reaches the Red Planet, it will join an even shorter list of nations that have pulled off a successful mission. Only the US, Russia and Europe have managed that.

For Ms Sampath, working on the Mars project was a dream come true.

The moment of lift-off

"I was in [my last year at primary school], when I saw a live launch on TV. At that time it just struck me in my mind how good it would be to work there, and today I am here," she says.

She is one of 500 scientists who have laboured on the project, which was announced 15 months earlier by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

Ms Sampath and her team built three instruments for the spacecraft that will carry out the main experiments.

One, an infrared camera, can detect heat sources, while another can sniff out methane in the atmosphere, an indicator of life (though Nasa's Curiosity has already ruled this out).

"I said goodbye to Saturdays and holidays in the two years before the launch. We were working up to 18-hour days sometimes," she says.

Ms Sampath is one of the few women working at the Indian equivalent of Nasa.

Despite that, she says she has never felt that she is treated any differently.

"I forget I am a woman sometimes, working in such an organisation," she says.

"Maybe it's because we spend a lot of time working in clean rooms with full suits on, so you can't tell who is male or female," she says, laughing.

But as only one in 10 of the scientists is female, Ms Sampath says this is something she wants to change. "I want women to imagine that they can do this."

Away from her family

The next stress point in her life will be when the spacecraft gets to Mars in September and all the systems reawaken to complete the mission.

Inevitably, this will mean she is away from her family.

"What the job takes away from me is that when my son is sick, when he needs me, I am in Bangalore repairing some system there," she says.

"I am not able to take care of him when he needs me but I am doing something with my payloads there, making connections, checking interfaces and making that all right.

"Without them, I wouldn't have been able to make such commitments to my work, five projects, eleven payloads."

However, Ms Sampath is adamant that she has not been unfairly treated

"It's all about your take on life," she insists, adding that she is "OK" with having her life disrupted by work.

"You have to keep dreaming, to keep thinking of what you will achieve. It is only up to you. Only you yourself can tune your life."

Message of inspiration

With her work firmly supported by the traditional extended Indian family structure, the prospect of much higher wages abroad has no appeal for her.

"I want to become the first woman director of a space centre," Ms Sampath says, and she would love to go into space herself, although she says she is likely to leave that to the next generation.

"I'm telling [my son] to save up to be a space tourist," she says.

And whether India should have spent $73m (£50m) on a Mars mission with so many of its people living in poverty, Ms Sampath is adamant that it is value for money as space exploration sends a vital message of inspiration to every Indian.

"It will not feed a single poor person but that poor person can think that 'in my country, look what is here!' It will make your thinking broad."

Also, she points out, the cost of India's Mars mission is less than the average Hollywood blockbuster.