Missing Malaysia plane MH370: What we know

- Published

The missing Malaysia Airlines plane, flight MH370, had 239 people on board and was en route from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing on 8 March 2014 when air traffic control staff lost contact with it.

The search for the plane eventually focused on a 120,000 sq km area of seabed about 2,000km off the coast of Perth in the southern Indian Ocean. It has now been suspended with no trace of the aircraft found there, and is likely to remain the world's greatest aviation mystery.

This is what we know.

Watch the video below to find out about the jet's last known movements.

What happened the day the plane disappeared?

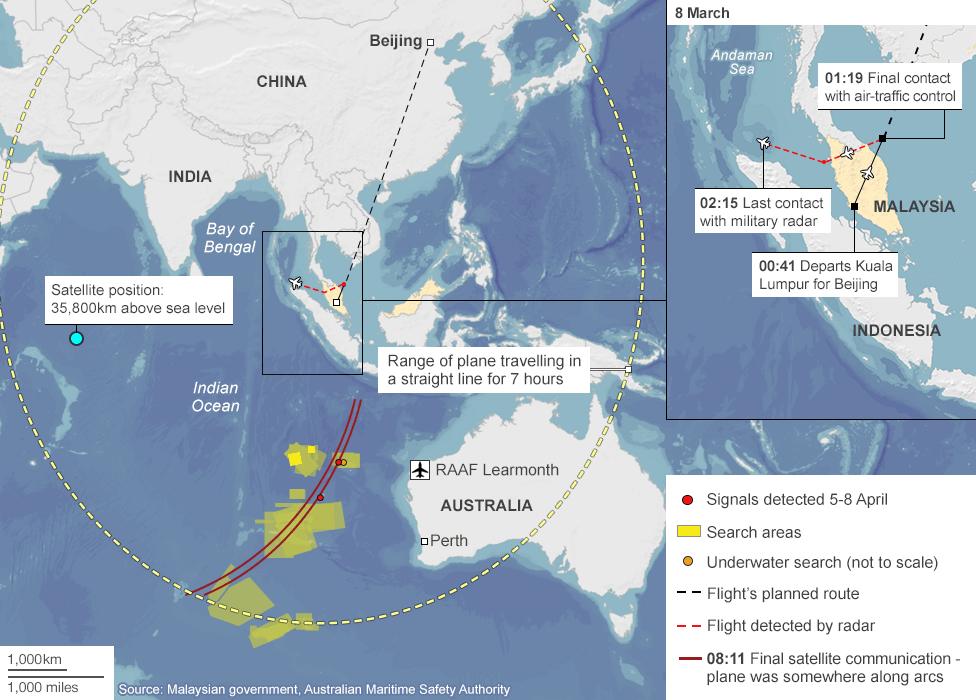

00:41, 8 March 2014 (16:41 GMT, 7 March): Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 departed from Kuala Lumpur International Airport and was due to arrive in Beijing at 06:30 (22:30 GMT).

Malaysia Airlines says the plane lost contact less than an hour after take-off. No distress signal or message was sent.

01:07: The plane sent its last ACARS transmission - a service that allows computers aboard the plane to "talk" to computers on the ground. Some time afterwards, it was silenced and the expected 01:37 transmission was not sent.

Flight MH370: Audio recording reveals final cockpit communications

01:19: The last communication between the plane and Malaysian air traffic control took place about 12 minutes later. At first, the airline said initial investigations revealed the co-pilot had said "All right, good night".

However, Malaysian authorities later confirmed the last words heard from the plane, spoken either by the pilot or co-pilot, were in fact "Good night Malaysian three seven zero".

A few minutes later, the plane's transponder, which communicates with ground radar, was shut down as the aircraft crossed from Malaysian air traffic control into Vietnamese airspace over the South China Sea.

01:21: The Civil Aviation Authority of Vietnam said the plane failed to check in as scheduled with air traffic control in Ho Chi Minh City.

02:15: Malaysian military radar plotted Flight MH370 at a point south of Phuket island in the Strait of Malacca, west of its last known location. Thai military radar logs also confirmed that the plane turned west and then north over the Andaman sea.

In maps accompanying its 1 May report, the Malaysian government revised the time to be 02:22 and put the position further west, external.

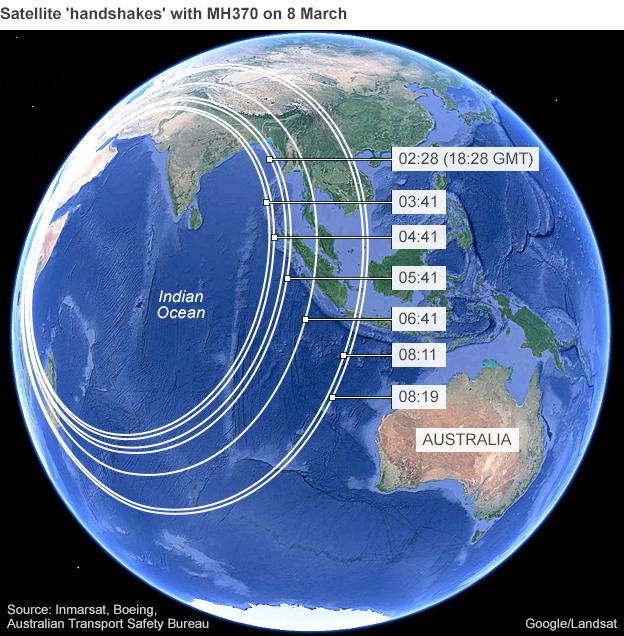

02:28 (18:28 GMT, 7 March): After the loss of radar, a satellite above the Indian Ocean picked up data from the plane in the form of seven automatic "handshakes" between the aircraft and a ground station. The first was at 02:28 local time.

08:11: (00:11 GMT, 8 March) The last full handshake was at 08:11. This information, disclosed a week after the plane's disappearance, suggested the jet was in one of two flight corridors, one stretching north between Thailand and Kazakhstan, the other south between Indonesia and the southern Indian Ocean.

08:19: However, there is some evidence of a further "partial handshake" at this time between the plane and a ground station. This was a request from the aircraft to log on. Investigators say this is consistent with the plane's satellite communication equipment powering up after an outage - such as after an interruption to its electrical supply., external

09:15: This would have been the next scheduled automatic contact between the ground station and the plane, but there was no response from the aircraft.

The search

The plane's planned route would have taken it north-eastwards, over Cambodia and Vietnam, and the initial search focused on the South China Sea, south of Vietnam's Ca Mau peninsula.

But evidence from a military radar, revealed later, suggested the plane had suddenly changed from its northerly course to head west. So the search, involving dozens of ships and planes, then switched to the sea west of Malaysia.

Further evidence revealed on 15 March 2014 by the Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak suggested the jet was deliberately diverted by someone on board about an hour after take-off.

After MH370's last communication with a satellite was disclosed, a week after the plane's disappearance, the search was expanded dramatically to nearly three million square miles - about 1.5% of the surface of the Earth.

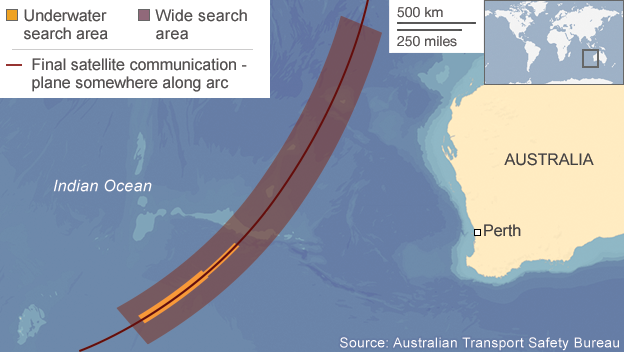

However, from 16 March, tracking data released by the Malaysian authorities appeared to confirm that the plane crashed in the Indian Ocean, south west of Australia, with possible locations refined following further satellite analysis.

There were a few false positives along the way. In early April 2015, Australian and Chinese vessels using underwater listening equipment detected ultrasonic signals, which officials believed could be from the plane's "black box" flight recorders. The pings appeared to be the most promising lead so far, and were used to define the area of a sea-floor search, conducted by the Bluefin-21 submersible robot.

Nothing was found and it was only in December 2015 that Australian officials said they had refined the search area and were confident they were looking in the right area for the plane.

Searchers combed the southern reaches of the Indian Ocean

In the end, an Australian-led search using underwater drones and sonar equipment deployed from specialist ships loaned by various nations combed a vast 120,000km area of the Southern Indian Ocean - but turned up nothing.

In December 2016 investigators admitted the plane was unlikely to be in that search area and recommended searching further north. , external

Experts identified a new area of approximately 25,000 sq km to the north of the current search area that had the "highest probability" of containing the wreckage. This was the last area the plane could possibly be located, given current evidence, the report said.

But Australia ruled out continuing the search beyond its scheduled end.

Areas searched up to January 2017

Debris discovered

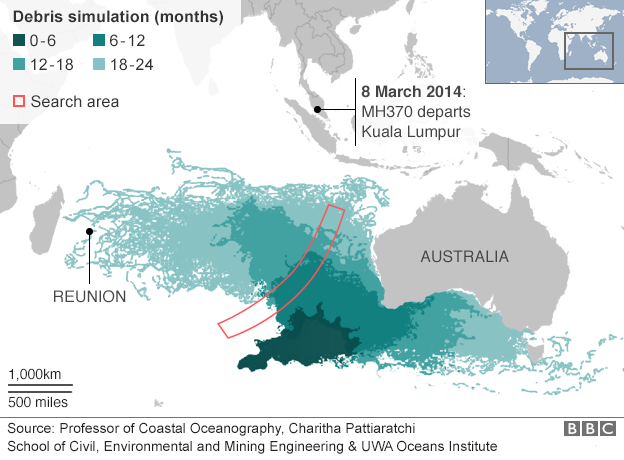

Although the underwater search turned up nothing, it was along a coastline thousands of miles away that clues began to wash up on beaches.

On 29 July 2015, a 2m-long (6ft) piece of plane debris was found by volunteers cleaning a beach in St Andre, on the north-eastern coast of Reunion.

On 5 August, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak announced that investigators had "conclusively confirmed" the debris was from the missing plane, a finding confirmed by French officials.

However, officials said this did not affect their search plans, as the debris had been carried to Reunion by ocean currents.

It was the first of more than 20 pieces of possible debris found by members of the public, on the African coast and islands in the Indian Ocean.

In November 2016, a report found the recovered wing flaps from the plane were not in the landing position when the plane went down in the Indian Ocean.

It was a significant finding that helped investigators say with more certainty that the flight most likely made a rapid and uncontrolled descent into the Indian Ocean.

So some bereaved families of those on board the flight are determined to keep the hunt for these clues going.

Who was on board?

Muhammad Razahan Zamani (bottom right), 24, and his wife Norli Akmar Hamid, 33, were on their honeymoon on the missing flight. The phone is being held by his stepsister, Arni Marlina

The 12 crew members were all Malaysian, led by pilots Captain Zaharie Ahmed Shah, 53, and 27-year-old co-pilot Fariq Abdul Hamid.

There were 227 passengers, including 153 Chinese and 38 Malaysians, according to the manifest, external. Seven were children.

Other passengers came from Iran, the US, Canada, Indonesia, Australia, India, France, New Zealand, Ukraine, Russia, Taiwan and the Netherlands.

Two Iranian men were found to be travelling on false passports. But further investigation revealed 19-year-old Pouria Nour Mohammad Mehrdad and Delavar Seyed Mohammadreza, 29, were headed for Europe via Beijing, and had no apparent links to terrorist groups.

Among the Chinese nationals was a delegation of 19 prominent artists, who had attended an exhibition in Kuala Lumpur.

Malaysia Airlines said there were four passengers who checked in for the flight but did not show up at the airport.

The family members of those on board were informed in person, by phone and by text message on 24 March that the plane had been lost.