Sherpa families' sorrow after killer Everest avalanche

- Published

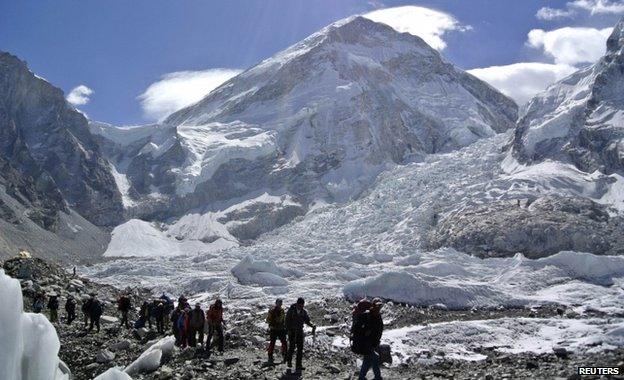

Around 9,000 Sherpas are engaged in mountaineering, working as guides and helpers

Menuka Magar-Gurung is struggling to come to terms with what happened on that bright, sunny morning.

Her husband, 29-year-old Aash Bahadur Gurung, was one of the Sherpa climbing guides caught up when a huge mass of snow suddenly gave way a few hundred metres above Everest Base Camp as they prepared for the climbing season.

"I still feel he's alive," the 25-year-old told the BBC, struggling to control her tears as she carried her 10-month-old son, Anish Gurung.

"Before going to Everest, he said it was his last time to work as a guide.

"He wanted to go to America. He wanted to make some money and make our lives better."

Menuka Magar-Gurung is struggling to come to terms with losing her husband

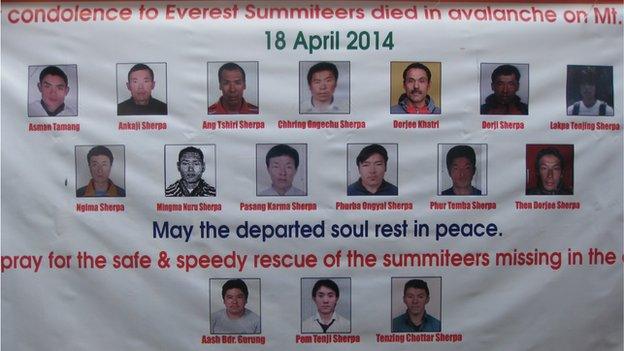

Sixteen Sherpas lost their lives on 18 April in what has been described by many as modern mountaineering's deadliest single tragedy. Three of them have not been found and are presumed dead.

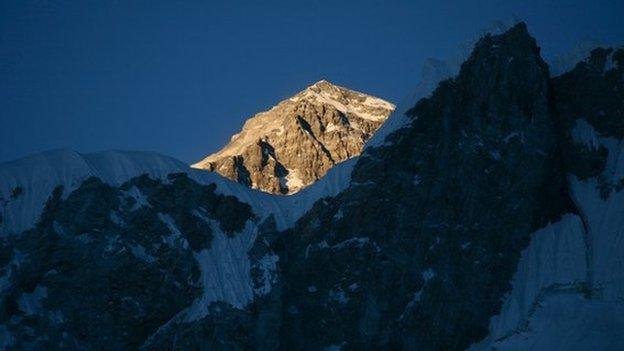

Since the avalanche, more than 300 international climbers have abandoned their plans to scale Mount Everest - the world's highest mountain at 8,848m (29,029ft), which straddles the border between China and Nepal.

Nepal's tourism and mountaineering authorities have been left high and dry.

'Treated miserably'

Anita Lama, 23, is the widow of Asman Tamang, 26, who also died on the mountain.

"I never thought that such a tragedy would happen," she told the BBC, her eyes welling up as she carried her daughter, 11-month-old Dolma Tamang.

Anita Lama says her husband had been working on the mountain for about four years

"He started going to the mountains for work for the past four years or so.

"Before the accident he said he would come back after two months. He was planning to build our own house after a couple of years."

After the disaster struck, the Nepali government announced a compensation and insurance package worth about $15,000 (£8,800) to the families of the Sherpa climbers.

But the families and friends of those killed were not satisfied.

Nimi Sherpa, who is a climber herself and an aunt of Phurba Ongyal Sherpa, 25, who also died in the avalanche, said the government had insulted the country's climbing community by initially announcing compensation worth merely $400 (£238).

"We are being treated like beggars," she said.

"We were treated miserably in the past, too, that's why many Sherpas have left the country."

Fraught with risks

Nepal's Himalayan Sherpa people are believed to have migrated from eastern Tibet centuries ago, and their population in Nepal currently stands at just over 112,000, according to Nepal's Population and Housing Census 2011.

The term "Sherpa" is now widely used to identify a climbing guide, and not all come from the ethnic Sherpa community of Solukhumbu, the district where Mount Everest is located.

According to the Nepal Mountaineering Association (NMA), around 9,000 Sherpas are engaged in mountaineering working as guides and climbing aides, and they make between $5,000 (£3,000) and $7,000 each climbing season - several times higher than the average Nepali income.

But the job is fraught with risks and there is no proper official social security arrangements, senior Sherpas say, so thousands have chosen to migrate to greener pastures.

Many have gone to America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand, and others to neighbouring India.

'Packed up'

After the avalanche, Nepal's tourism and mountaineering officials were unable to persuade the 300 international climbers at the Everest Base Camp to continue climbing.

"All climbers have packed up and left the base camp by now," Ang Tshering Sherpa, president of the NMA, told the BBC.

"But the expedition plans from the Chinese side of the mountain are on."

In recent years, Nepal's tourism ministry has been earning an annual sum of more than $3m (£1.7m) from the climbers heading to Mount Everest alone.

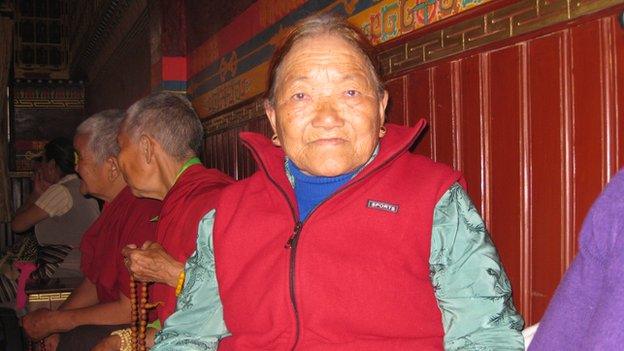

Nima Sherpa is concerned about who will provide for her grandchildren

After the disaster on 18 April, officials decided to extend the permits issued this year for five years. They also announced better rescue and security measures for mountaineers.

As well as the security measures, the government announced education and welfare benefits for the families of those Sherpas killed.

Worried for the future

But 77-year-old Nima Sherpa, who lost her youngest son, Ang Kaji Sherpa, 37, in the avalanche, is still worried that her six grandchildren may suffer.

"He went to the Himal [mountain] to make money, earn daily bread for the family, build a house. Now who will do that?" she asked, as she joined prayers organised in memory of her son at a Sherpa monastery in Kathmandu.

Her granddaughters Chhechi Sherpa, 19, and Sumi Sherpa, 15, go to school in Kathmandu, but now, after the sudden death of their father, they are worried about their future.

"The government must help us complete our education," Chhechi said. "It must also give us facilities such as taking up government jobs."

In the weeks since the avalanche, some Sherpas at the Everest Base Camp have demanded seats in parliament and access to civil service roles such as mountain liaison officer assignments - a job assigned to mostly non-Sherpa Nepali officials until now.

Tourism Minister Bhim Acharya responded to this, saying: "The government is serious about the demands put forth by our brave Sherpa climbers. We are doing whatever we can.

"But as far as a government job without the proper qualifications and education is concerned, that's not possible because we have to follow the rules and laws."

Wangchu Sherpa, president of Nepal Climbers Association, says it is not always fair to blame the government for all the problems facing the Sherpa community.

The group of 16 Sherpa climbers were hit as they made preparations for the climbing season

"There was no provision for compensation until a few years ago," he said. "Gradually things are improving for the Sherpas. There are provisions for compensations, education and welfare. That's a good thing."

Shailee Basnet, a member of Nepal's all-women expedition team called Seven Summits Women Team, thinks emotions are too raw now.

"The Sherpas will go back to Everest again next year," she said. "That's why the government and the climbing operators must ensure the technical, social and economic safety of the Sherpa climbers."

Warmth and support

Ang Tshering, president of the NMA, told the BBC he welcomed the government's efforts, and said his organisation had decided to set up a separate trust worth $100,000 (£60,000) for the bereaved families.

But he said the association was calling for the insurance package for Sherpa climbers to be increased to $2m (£1.2m).

Since the 1960s, Nepal's Sherpa community has increasingly received support from international groups.

New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary, who became the first man to reach the summit of Everest in 1953 along with Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, founded the Himalayan Trust in 1960, which helped to build airstrips, schools and hospitals in the Everest region. Since then other charitable individuals and organisations have followed suit.

International climbers have continued to show warmth and support since last month's avalanche. Japanese climber Ken Noguchi gave $100,000 (£60,000) towards the education and welfare of the deceased Sherpas' families.

"It's very sad that the Sherpas went to the extent of boycotting climbing expeditions this year," Mr Noguchi told the BBC. "It probably reflects their long pent up anger and resentment.

"It's good to see the government and the mountaineering association extending support to them.... Such incidents shouldn't happen in the future."

- Published25 April 2014

- Published25 April 2014

- Published22 April 2014