Sherpas make a stand as Everest avalanche takes its toll

- Published

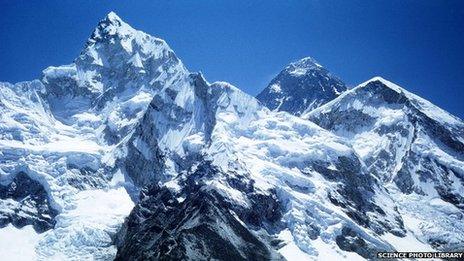

The avalanche that struck above Everest base camp last week killed 16 local guides

All climbing on Mount Everest has come to a halt amid chaotic scenes at base camp, according to climbers there, four days after the worst-ever accident on the mountain.

Some local guides are calling for a boycott but most foreign mountaineers remain on the mountain and are still hoping to resume climbing in the next week or so.

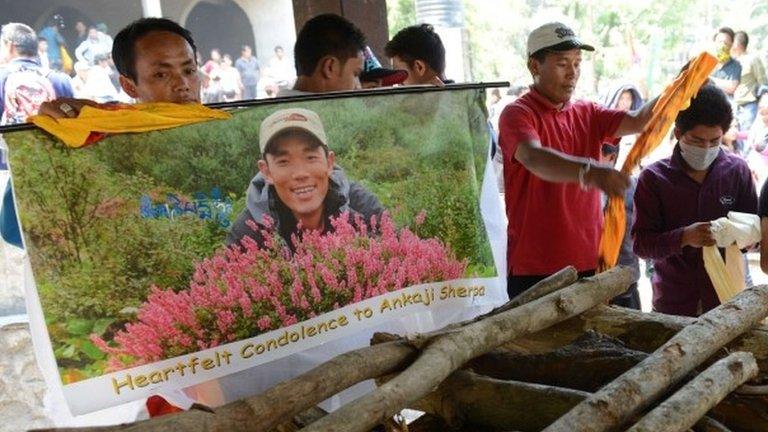

A "puja" ceremony on Tuesday for the 16 sherpa climbing guides killed by last Friday's avalanche descended into a surge of furious chanting and calls for all climbing to be suspended, according to several mountaineers present.

"They are very angry and very militant," the leader of one climbing team told the BBC from Everest base camp, asking that he not be identified. So far, he said, their protests "are all aimed at the government, not at the climbing companies".

'Wake-up call'

The disaster has brought to the surface long-simmering tensions over how the government shares out millions of dollars in revenue from the annual pursuit of the Everest summit, with sherpas denouncing its initial $400 (£240) compensation offer for the families of their dead compatriots.

But the expedition leader said the disaster was a "wake-up call" for the whole climbing business and that "things would have to change".

The tragedy has highlighted what all those who climb the mountain know - that Nepalese guides take most of the risks and most of the load. But commercial climbing on Everest and other big peaks has also become crucial to Nepal's economy.

The families of the sherpa guides who died denounced the Nepalese government's initial offer of compensation

The Sherpas were caught in the avalanche as they were making their way up the Khumbu icefall, a treacherous mass of ice boulders and crevasses that has long been one of the most dangerous parts of the route.

These high-altitude climbing Sherpas can earn up to $8,000 (£4,800) in the three-month Everest season, more than 10 times as much as the average wage in Nepal, which remains one of Asia's poorest nations. Even the lowest paid porters who haul supplies up to Everest base camp do better.

But that doesn't look so good when the Nepali government is earning millions of dollars each year in fees for climbing permits and with some commercial guiding companies charging clients up to $60,000 (£36,000) per person, with more than 300 paying mountaineers this year.

Delaying tactic?

A panicked Nepali government has now reportedly agreed to many of the sherpas' demands for better compensation and a relief fund - but sceptics fear this is a delaying tactic to make sure it doesn't have to refund millions of dollars in climbing fees.

Many of the climbing companies see the sherpas' point of view, according to the expedition leader. "The principle of their demands does not look unreasonable," he said. "It's just a matter of degree."

But they are feeling the pressure. Some have sent their sherpas down the mountain, to try to avoid them being sucked up into the current angry mood at base camp.

Wingsuit jumper Joby Ogwyn planned to leap from Everest but the company behind the stunt pulled its support

One American company behind a climber planning to jump from the summit in a wingsuit has pulled out altogether, as a mark of respect, as some of the sherpas who died were its employees.

It's stunts like that that have helped stir the now annual controversy over Everest, which has become almost as much of a fixture in the media calendar as the May "weather window" that all the mountaineers gather for.

Pictures of backed-up lines of down-suited climbers queuing to take the last steps to the summit are now bedded into popular consciousness. Editors know there is something about the business of paying tens of thousands of dollars to climb the world's highest peak that annoys their readers.

It's true that the modern Everest scene all seems a far cry from the days when pioneering British climber George Mallory explained the draw of the peak by simply saying: "Because it's there."

But what looks like extravagant madness to some now provides critical employment to many. With tens of thousands of climbers and trekkers from all over the world coming to the Everest region every year, it has become the wealthiest part of the country outside of the capital Kathmandu.

Few of the thousands of Nepalis who have travelled for poorly-paid jobs helping to build the World Cup in Qatar - where many have died - come from the Everest region. There's better paid work on their doorstep.

'Under threat'

The angriest voices are dominating at Everest base camp, according to people there. But there are many who want to return to work. "All my Nepali staff are still here," said the climbing leader.

But he admitted the disaster is having a salutary affect on the commercial guiding world. "We are under threat now," he said. "The old model can't continue."

Pressed on what changes he foresaw, he said, "I can't tell you yet."

- Published21 April 2014

- Published20 April 2014

- Published18 April 2014