Abduction of activist Zahid Baloch highlights Balochistan plight

- Published

Pakistani activist and Baloch nationalist Zahid Baloch was abducted earlier this year and his whereabouts remain unknown. The BBC's Shahzeb Jillani, who interviewed him six months before his abduction, reports on the case.

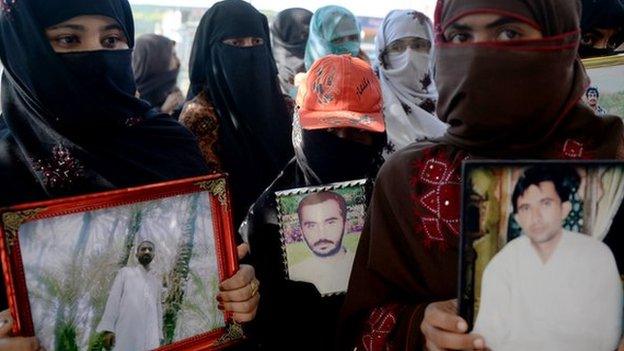

In Karachi's sweltering summer heat, at a protest camp outside the city's main press club, Lateef Gohar, a young man in his early 20s, is lying stretched out on a footpath.

Sitting next to him are a few colleagues, mostly women with their faces half-covered in their traditional headscarves.

Mr Gohar has refused food since 22 April. With every passing week, he is losing weight and his health is deteriorating.

The hunger strike is to protest against the alleged abduction of a nationalist student leader, Zahid Baloch, by Pakistani security forces.

Mr Baloch, who heads the separatist Baloch Student Organisation (Azad), was picked up in a security raid in Quetta, the capital of Balochistan province, on 18 March.

Soldiers from an official paramilitary force, the Frontier Corps, are said to have held him at gunpoint. He was blindfolded and his hands tied behind his back.

He was then pushed into a vehicle by men in plain clothes thought to be from Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), say his colleagues.

The alleged abduction took place in broad daylight, in front of three of his female colleagues and several people in the local area.

Two months on, no-one knows where he is.

Given similar abductions in the past, his colleagues fear the student leader is being tortured.

Mr Baloch's wife, Zarjaan, and two boys, aged two and four, are not sure if they will get to see him again.

The family and colleagues of Mr Baloch went to the police to register a complaint against his alleged enforced disappearance. But officials refused to lodge their case.

For 10 days, they kept going back to the police station.

Zahid Baloch told the BBC the Baloch Student Organisation are engaged in a non-violent struggle for self-determination

Finally, they were told that a case cannot be lodged against members of powerful security agencies.

Writer or fighter

Six months before his abduction, I met Zahid Baloch at a remote unknown location in District Awaran, Balochistan. At the time, he introduced himself to us as Baloch Khan.

He told us he was forced to live in hiding because of Pakistan's alleged "kill and dump" policy targeting Baloch separatists. "If they find me, they'll kill me," he told us back then.

Zahid Baloch insisted his was a political struggle for self-determination.

"Whether you are a writer or a fighter, in Balochistan if you talk about freedom, they come after you," he had said.

"Pakistan, and even Iran, have subjugated the Baloch people. They want to erase our language, culture and heritage. The only way we can win freedom is through a national struggle."

But Pakistani officials accuse people like you of getting support from India, I put to him.

He smiled and replied: "They said that about Bengalis as well. They went on a killing spree to suppress their freedom struggle in 1971. And look what happened? It created Bangladesh."

The Pakistani government outlawed Mr Baloch's Azad group in March 2013 along with a dozen other militant and radical factions.

'Self-disappearances'

Officials accuse Azad of spreading anti-Pakistan literature on college and university campuses.

"The group serves as a nursery for recruiting fighters for separatist Baloch militants," says Sarfaraz Bugti, Balochistan's home minister.

He denies any knowledge of Mr Baloch's whereabouts. "I have never heard of him. I am not even sure if a person by that name exists," he told the BBC.

But Mr Bugti rejects widespread allegations of torture and abductions. Instead, he likes to talk about "self-disappearances" to explain what is going on in his province.

"Sometimes, these activists 'self-disappear'. They go away to militant training camps in Afghanistan and India, while their groups stage campaigns to wrongly accuse Pakistani forces of abductions."

Rights activists say Zahid Baloch's case is the latest example of years of ongoing "enforced disappearances" in Balochistan. For more than a decade, the accusations have continued to grow. And so have the protests by desperate families.

Historic protest

Earlier this year, relatives of missing persons marched on foot from Quetta to Karachi and then from Karachi all the way to the capital, Islamabad, covering a distance of more than 2,000km (1,200 miles) in four months, to demand an end to rights abuses and arbitrary detentions.

It was seen as a historic peaceful protest, involving women, children and Mama Qadeer, a 72-year-old man whose son was abducted, tortured and killed by security forces a few years ago.

But the march failed to move the Pakistani authorities. And now, Mama Qadeer is back to where he started - at a protest camp for missing persons in the city of Quetta.

This despite numerous judgements by the Pakistani Supreme Court in recent years acknowledging the role of security forces in arbitrary detentions and rights abuses.

Activists say none of it has made any difference to the culture of impunity the country's security agencies enjoy in the province.

"The state has no right to hold Zahid Baloch and others like him in secret detention," says Nasrullah Baloch, head of a campaign group, Voice of Missing Baloch Persons (VMBP).

During the last five years, his group has recorded 2,900 cases of "enforced disappearances".

Pakistani officials reject the figure, saying they are only aware of a few dozen cases.

"All we ask is that, if these men have done anything wrong, they should be brought before police and tried in a court of law."

Back at the protest camp in Karachi, Lateef Gohar's hunger strike continues.

He is increasingly suffering from weakness, headaches and nausea.

"We are looking to international rights groups and nations who stand up for the rule of law and human rights," says a colleague caring for him at the protest camp.

"They need to ask the Pakistani state why it hates the Baloch so much."

- Published22 February 2014