Pakistan Taliban still deadly despite split

- Published

The Pakistani Taliban's latest attack was well co-ordinated

The Karachi airport attack comes against the backdrop of a major split in the Pakistani Taliban (TTP) - and threats of retaliation following limited military operations against foreign militants in North Waziristan.

Given the violence it seems clear that any pretence at a peace process is now over. Few seriously thought that recent talks between the government and militants were getting anywhere anyway.

The attack is also a reminder, if it were needed, that despite their divisions the Taliban retain the capability to mount spectacular strikes across Pakistan.

The Karachi raid comes at a time when significant re-alignments are in the offing within militant ranks ahead of the Nato drawdown of combat troops in Afghanistan later this year.

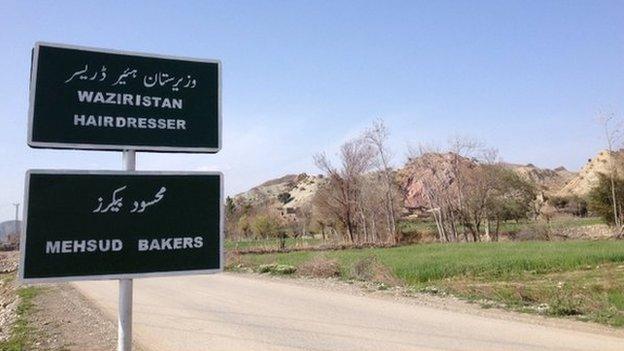

Both North and South Waziristan, along with other tribal districts, are strongholds for Taliban militants

The split within the TTP is the clearest symptom of these changes.

The TTP was founded, and invariably headed by, a Mehsud tribesman from the South Waziristan tribal region. But last November, after its former leader Hakimullah Mehsud was killed in a US drone strike, its leadership passed into the hands of Mullah Fazlullah, a non-Mehsud from Swat region.

This, combined with an offer of peace talks by the Pakistani government, led to an internal struggle between the powerful Mehsud faction and the non-Mehsud elements.

Former BBC correspondent Rahimullah Yousufzai, who is an expert on Taliban affairs, says one reason the Mehsuds fell out with the TTP leadership was because of their keenness to hold peace talks.

"The Mehsud tribe has suffered the most in Pakistan's war against militancy," he says.

"The 2009 military operation in their area scattered them into far-off cities such as Lahore and Karachi where people view them with suspicion. They don't live normal lives. This has created pressures on their leaders to mend fences with the government and pave the way for their rehabilitation."

The Mehsud faction, led by Khalid Mehsud (alias Khan Said Sajna), not only wiped out their TTP rivals from their native South Waziristan, they also captured most TTP strongholds in Karachi.

But Sunday night's attack shows the groups allied with Mullah Fazlullah's TTP still have secure hideouts in the country's largest city and the capability to launch attacks on high-value targets there.

The situation is further complicated by a warning issued to local people by Hafiz Gul Bahadur, who heads a powerful Taliban faction in North Waziristan, at the end of May, asking them to move to safer locations "before hostilities break out with the government".

He was apparently incensed over some limited military action in a village near the town of Miranshah from where locals say foreign militants, predominantly Uzbeks, were "flushed out and encouraged to cross the border into Afghanistan".

Locals in Miranshah say most foreigners have left the area. Many have headed into Afghanistan, but many more have slipped into Pakistan. They say it is not clear if an alternative sanctuary is emerging in Afghanistan's Khost area, which has recently been vacated by the Americans.

Unlike the TTP, which has fought inside Pakistan, Hafiz Gul Bahadur has had a peace agreement with Islamabad since 2007, and has entirely focused his attention on foreign troops stationed in Afghanistan. He also has a close working relationship with the Mullah Nazir group which controls the western half of South Waziristan, has a similar peace agreement with Islamabad, and has been exclusively fighting inside Afghanistan.

Analysts believe that both these groups view the TTP split as the handiwork of Pakistani intelligence agents who play one faction against another to advance their own interests in Afghanistan, a suggestion denied by Islamabad but which few believe.

"There is a fear among the Bahadur and Nazir groups that if Pakistan succeeds in bringing the TTP to its knees, they will become redundant at best, and may suffer a similar fate at worst," says Khadim Hussain, an expert on militancy and author of the book Militant Discourse.

Karachi has been a target for many attacks by the Taliban

But these are not the only elements in the Waziristan matrix. For more than a decade, the area has been a sanctuary for Afghanistan's Haqqani Network, and thousands of "outsiders" - militants from Central Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, north-western China, and other parts of Asia and South Asia, including Punjab province in Pakistan.

Most of these "outsiders" have little interest in promoting peace with either Islamabad or Kabul, and are likely to align with those native factions that aim to create a permanent post-Nato sanctuary in areas comprising southern and eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan's tribal region and parts of its Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

Uzbek militants of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), who are believed to have taken part in the attack on the airport, are one such group. DNA tests will be conducted to try to verify if any of the militants killed were Uzbeks.

Either way, the authorities have warned a council of elders in North Waziristan to expel foreign militants from their area.

What happens now to Pakistan's fast-changing militant alliances remains unclear - but the backdrop to the Karachi attack is far more complex than it appears at first glance.

Who are the Pakistani Taliban?

•With its roots in the Afghan Taliban, the Pakistani Tehreek-e-Taliban movement came to the fore in 2007 by unleashing a wave of violence

•Its leaders have traditionally been based in Pakistan's tribal areas but it is really a loose affiliation of militant groups, some based in areas like Punjab and even Karachi

•The various Taliban groups have different attitudes to talks with the government - some analysts say this has led to divisions in the movement

•Collectively they are responsible for the deaths of thousands of Pakistanis and have also co-ordinated assaults on numerous security targets

•Two former TTP leaders, Baitullah Mehsud and Hakimullah Mehsud, as well as many senior commanders have been killed in US drone strikes

•It is unclear if current leader Maulana Fazlullah, who comes from outside the tribal belt, is even in Pakistan, but he has a reputation for ruthlessness

- Published9 June 2014

- Published9 June 2014

- Published9 June 2014

- Published12 August 2022

- Published15 April 2014