Afghan elections: Voting for a better future

- Published

Both candidates have made surprising transformations during the contest

As Afghanistan stands at a crucial turning point that will determine its political future, its past still stubbornly lingers.

"We met nearly 30 years ago, during President Najibullah's time," a smiling police officer reminds me as we approach the main command centre in the heavily fortified Interior Ministry in Kabul.

Brigadier General Nematullah Haidery is now the chief of operations overseeing a newly-renovated communications hub for the massive security in place for a second round of voting in the presidential race.

Afghans who've lived through all the devastating wars since President Najibullah's Soviet-backed rule are hoping this election will help turn the page on their punishing history.

It will be the first time in Afghan history that power is transferred peacefully, from one elected leader to another.

Months of vigorous campaigning, and an impressive turnout in the first round of voting, were a strong testament to a country determined to move forward in the face of Taliban threats and violence.

But the two men now facing off in this second decisive round still carry the baggage of their previous lives.

Critics of Dr Abdullah Abdullah say his presidency will deepen cronyism and corruption in the country

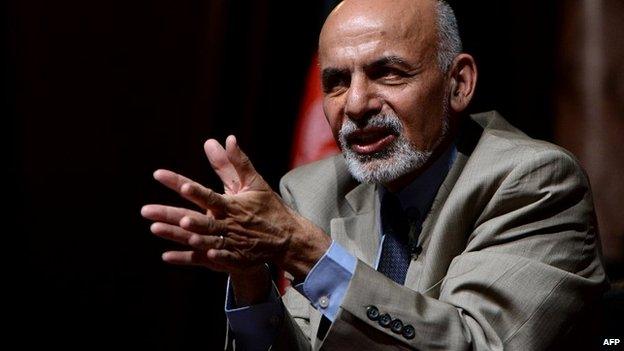

Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai has faced criticism for previously leaving Afghanistan to live in the US

For some Afghans, former Foreign Minister Dr Abdullah Abdullah is the candidate of the Northern Alliance, the military front formed to confront the Taliban in the mid-1990s, largely comprised of Tajik commanders who fought against Soviet occupation. His critics fear his presidency would further entrench powerful warlords and deepen cronyism and corruption.

Other Afghans point out that former World Bank economist and ex-Finance Minister Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai spent the demanding decades of war in the United States. His critics worry about his perceived intellectual arrogance and infamous short temper.

Uniquely qualified?

And yet both men have made surprising transformations in the heat of this crucial contest.

Dr Abdullah, who has mixed Tajik and Pashtun ethnicity, has forged alliances with Afghans that cut across many deep divides. In the first round of voting, he took a commanding lead of 45% in a country where presidents and kings have traditionally emerged from the majority Pashtuns.

And Ashraf Ghani has criss-crossed the country in traditional tribal attire reaching out to Afghans from all walks of life, with all sorts of worries. He's also learned lessons from his first presidential bid in 2009, which won him a paltry 2.9% of the vote.

There is massive security in place for a second round of voting in the presidential race

Both men have made deals with regional strongmen who bring vote banks rooted in ethnic or other longstanding loyalties.

Both are casting themselves as uniquely qualified to unify and build a country still struggling to emerge from the legacy of its long wars.

But this contest is also a reminder of how far Afghanistan has come since the fall of the Taliban in 2001 when the international community started pouring in money and troops.

Despite profound fears for the future once foreign forces leave and aid levels drop, Afghans are now focused on this chance to secure a smooth political transition.

Security advances

General Haidary's command centre is a high-tech hub with computers and video links connecting trained policemen in Kabul to bases across Afghanistan. A gaggle of American military mentors hover in a corner office but this is an Afghan operation.

During our visit, there are calls for helicopters to be dispatched to an area where police fear vehicles transporting ballot papers will be ambushed. Another police officer in a southern province appears on a video screen warning that clashes with Taliban are preventing election material from reaching some polling centres.

The control centre for security operations in Kabul is far more advanced than in previous years

On the other side of the sprawling Interior Ministry compound, the 119 emergency call centre has been upgraded since the 2009 elections when we visited a room of tables and constantly ringing telephones.

Now operators sit in phone booths taking calls from the public and there's also a site on Facebook.

"There were 3,600 calls on voting day during the first round," a beaming Colonel Humayoun Ainy informs us.

"In recent years, calls from Afghan citizens helped us stop 35 suicide attacks and find 6,000 land mines."

This is a country where, 13 years ago, you had to leave the country to make an international telephone call.

Challenges ahead

Despite all the disappointments and setbacks since 2001, Afghanistan is now a changed country.

When Afghans turn out to vote for this crucial second round, it will be a test of their security forces as well as the electoral institutions where Afghans are also in charge now.

It's also a challenge to aspiring presidents, and their teams, to play by the rules of these new political battles.

In his final news conference before voting day, UN envoy Jan Kubis underlined a responsibility "not to jump to conclusions" on election day.

Afghans are hopeful that the election will lead to a better future for them, but there are many challenges

Both Dr Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani were quick to claim victory in the first round, and their supporters have already been warning of consequences if fraud blocks their candidate from reaching the presidency.

Many worry that if the margin of victory is slim, the chances of recrimination, if not unrest, will be great.

"I voted for democracy in the first round," one Afghan analyst told me. "In this second round, I'm not sure who to vote for."

For many Afghans, this is a vote for a better future.

Six months ago, there were predictions this election would not happen, that President Karzai would find a reason to stay in power, that the Taliban would keep voters away.

So far, it's all turned out far better than many expected.

But now the hardest part is under way. It has the potential to help Afghanistan take a major step forward, or keep holding it back.

- Published7 July 2014

- Published13 June 2014

.jpg)

- Published7 July 2014

- Published12 June 2014

- Published13 June 2014