What Japan's military shift means

- Published

Japan's military will now be able to assist allies under attack, in certain circumstances

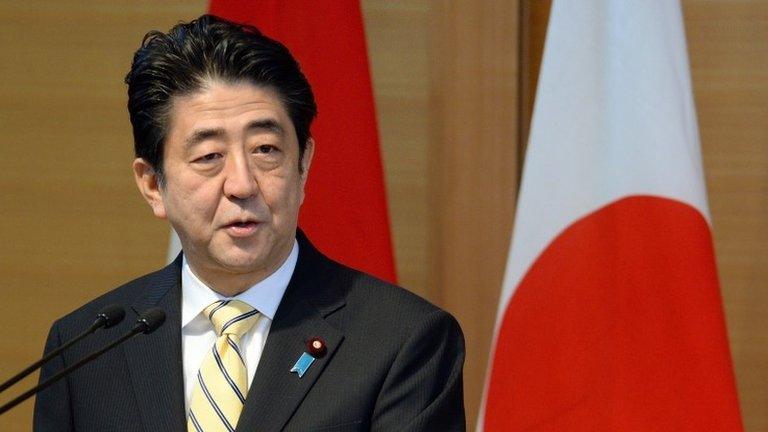

The administration of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has announced a major new interpretation of the security provisions of the country's 1947 constitution, permitting its Self Defence Forces (SDF) to participate for the first time in collective self-defence related activities.

In future, the SDF will, in principle, be able to assist the forces of a foreign country in situations where either the survival and security of Japan or that of its citizens is at risk.

The new interpretation is highly controversial since it represents a sharp departure from the post-war political consensus, codified in Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, that explicitly limits Japan's use of military force exclusively to the defence of its sovereign territory and its people.

Such has been the strength of post-war Japanese pacifist sentiment, and notwithstanding the long-term alliance with the United States, that Japan's defence forces have been unable to extend their military collaboration with their US allies beyond this narrowly circumscribed role.

Under the new provisions, there are now a range of scenarios in which this type of joint defence activity might be expanded.

Examples include providing defensive support to US forces under attack in the vicinity of Japan, co-operating militarily with US forces to safeguard Japanese citizens at risk overseas, participating in minesweeping activities during a time of war, or deploying Japanese forces to protect access to energy supplies or critically important sea-lanes of communication vital to Japan's survival.

Mr Abe has said Japan must change to adapt to a new security environment

Indeed, in theory, the new interpretation will allow Japan to co-operate with any foreign country with which it has "close ties", thereby substantially expanding the scope for military co-operation with different countries and beyond the narrow remit of the defence of Japanese territory.

Carte blanche?

Opinion in Japan is divided on the merits of this change, with 50%, according to a recent Nikkei poll, opposing the new interpretation and 34% supporting it. The motives for opposition are mixed, in part reflecting the unresolved debate about Japan's post-war political identity, but also prompted by uncertainty regarding the long-term security objectives of the Abe administration.

Progressive thinkers argue that the changes overturn the pacifist legal and interpretative conventions, established in the aftermath of World War Two, guaranteeing that Japan will never again become embroiled in foreign conflicts. Given the sensitivity and importance of these political norms, critics argue they should only be changed via constitutional amendment.

Entrenched pacifism at local level means that many oppose the change

While the Abe administration dominates both houses of the Japanese parliament, it is uncertain of its ability to revise the constitution rapidly and critics view the new interpretation as one of dubious political legitimacy.

There is also some fear, both within Japan and amongst its closest neighbours, most notably China and South Korea, that the new interpretation is intended to allow the government to deploy troops freely in a wide-range of conflict situations.

However, the Abe administration has explicitly ruled out such options and has been careful to distinguish between collective self-defence (intended to safeguard Japanese national interests and assets) and collective security - where states co-operate to protect their mutual interests in the face of foreign aggression. Mr Abe himself has made it clear that Japan's forces will not "participate in combat in wars such as the Gulf War and the Iraq War".

Strategic risk

Mr Abe appears to have a number of motives for introducing the new interpretation. It will provide Japan with much greater latitude to strengthen its military co-operation with the United States - something that Washington is keen to encourage as part of the current revision of the Joint US-Japan Defence Guidelines, unchanged since 1997.

It will also open the door potentially to more active defence co-operation with other countries in the Asia-Pacific region, such as Australia and the Philippines - both of which have welcomed these changes, as they look anxiously at China's increasingly assertive maritime posture in the South and East China seas.

Japanese troops went to Iraq as peacekeepers - but Mr Abe has ruled out fighting in an Iraq-like war

More generally, the new interpretation is likely to strengthen the perception that Japan has become a more "normal" state, in terms of its ability constructively to contribute to global and regional security.

The political and diplomatic dividends from such a change in attitudes are likely to be considerable, potentially strengthening Japan's long-standing bid for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and adding weight to Mr Abe's recently articulated strategy of making a "proactive contribution to peace".

The new approach is not without risk. While Japan's mainstream political parties remain weak and divided, citizen activism in opposition to these changes may be energised, particularly at the level of local politics. Prefectural, city, town and village-based criticism of the government's approach has been vocal and may cost the government support in the spring elections of 2015.

Abroad, the new measures look set to further undermine an already frayed relationship with South Korea and to heighten territorial and political tensions with China.

Finally, the intentional ambiguity surrounding the details of the new interpretation provides the government with useful flexibility in deploying its forces overseas, but it also magnifies the potential for increased tactical and strategic risk at a time when regional security tensions are intensifying.

For a Japanese government that has limited experience of the high-pressure challenge of national security decision-making and crisis management, this may not be an entirely positive development.

John Swenson-Wright is head of the Asia Programme at Chatham House.

- Published1 July 2014

- Published23 April 2014

- Published1 April 2014

- Published15 March 2012

- Published17 December 2013

- Published17 December 2013

- Published9 January 2013

- Published13 February 2014