Nepal blizzards: How to survive when disaster strikes

- Published

Nepalese soldiers have been bringing back those rescued from the recent avalanches

Officials have now confirmed dozens of deaths in snowstorms that have struck a popular Nepalese trekking route. As emergency teams continued their search experts told the BBC how hikers could stay as safe as possible if disaster strikes.

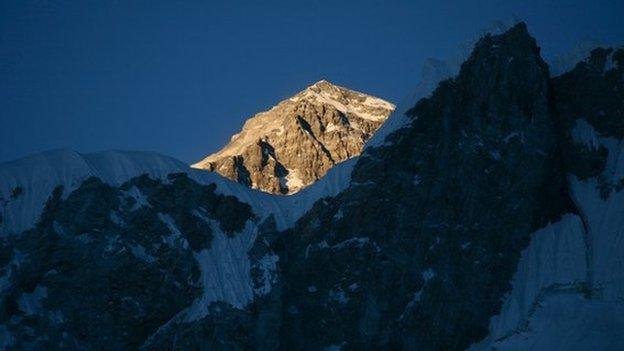

Dawa Steven knows all too well how quickly disaster can strike in the Himalayas.

As a Nepalese Sherpa, he has climbed widely in the surrounding peaks and said the weather can change in an instant.

The 30-year-old recalls the time two years ago when he and nine companions ran into trouble while climbing on the Tashi Labsta pass near Mount Everest.

"There was a sudden change in weather and a tremendous windstorm," he said. "It was horrendously difficult and very, very dangerous. Hands down, that was one of my toughest days."

In the latest storms, many people appear to have perished after being caught out on open mountainsides. Others were buried by avalanches.

The deadly weather was highly unusual, whipping through Nepal on the tail-end of Cyclone Hudhud.

Yet Mr Steven, who runs a trekking company in Kathmandu, said there were still life-saving tips which climbers could use to mitigate the risk of catastrophe.

Military helicopters were brought in to carry out search and rescue missions in Nepal

The one thing to remember was shelter, he said, even if it were a yak shed or tea hut.

"If there is no shelter, find a cave or a large rock somewhere," he said. "Just any sort of shelter from the elements.

"Then band up with other people. As it gets colder you can rely on each other's body warmth."

If a hiker is caught without any kind of sanctuary during a storm, he added, then he or she had almost "reached the point of no return".

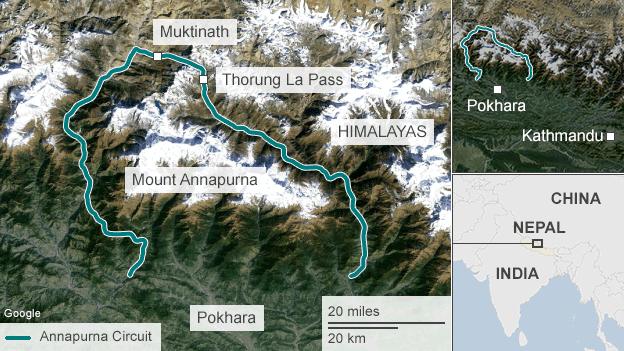

Tuesday's tragedy occurred on the Annapurna Circuit - one of the most well-trodden trekking routes in the world.

Although frequented by seasoned climbers and mountaineers, it is also popular with less experienced hikers.

Given the severity of the unexpected snowstorms, some of those caught out would not have had been fully prepared.

Simon Lowe, an experienced mountaineer who has climbed widely in Nepal, said: "You just would not expect that weather at this time of year.

"There would have been a reasonable expectation that they could have gone out in good weather and it would have stayed like that."

Preparing for the worst

Like Mr Steven, Mr Lowe said that the most important thing for any hiker to do in such a situation is find shelter - even if it means trying to create a snow cave.

How to avoid an avalanche

Though there is no failsafe method, assessing avalanche risk is mostly a matter of topography, say experts.

Convex slopes and cornices are particularly hazardous, while smooth rock slabs beneath the snow are dangerous as they fail to provide anchorage.

The type of snowfall is also key - the stickier the snow, the less likely it is to sheer off the mountain. In addition, if the sun is shining the day after a heavy storm, then melt-water running beneath the surface could also increase the chances of movement.

For walkers, the odds of surviving an avalanche come down to the surrounding terrain. If it looks like the risks of collapsing snow are high and you are standing on the edge of a crevasse or in a gully, the prospects of survival may be slim.

Even if caught in the flow of an avalanche, experts say, all is not lost. Rolling like a log or even using a swimming motion can help, while covering the mouth with one hand can help create a breathing space when trapped.

But he added that technology was becoming increasingly influential. Weather forecasts are readily available on mobile phones, he said, while his own company always sends groups to Nepal with satellite phones and GPS devices.

However he noted that in the worst storms, GPS technology often does not work.

Another problem is altitude sickness - something which Mr Lowe rates as the single biggest danger for hikers in the Himalayas.

According to Nikki Skinner from the UK-based Trek and Mountain magazine, a good way for walkers to mitigate the risk is to train at home before leaving on a big expedition.

"The best thing you can do is to replicate what you will be doing when you get there," she said. "You need to do cardiovascular fitness training, go for long walks, get used to long days on foot."

Ms Skinner also said there were various training programmes for trekkers, including rescue courses or "winter skills" programmes on how to spot avalanche threats or navigate during a blizzard.

Dawa Steven says that perhaps the most effective way for a trekker to escape catastrophe is to prepare adequately beforehand.

"It all starts before the trek itself," he said, saying that it was important for foreigners to use experience local guides and also inform their embassies of where they were going.

"These days Annapurna is popular with a lot of young people on a budget," he said. "They don't hire proper guides and don't go through proper trekking companies.

"Sometimes they are going into unknown territory and in 99% of cases that is fine. But when something like this happens, they can get into big trouble."

- Published17 October 2014

![Sgt Paul Sherridan [left] and Steve Wilson in the Himalayas](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/624/mcs/media/images/78303000/jpg/_78303311_sherridan2.jpg)

- Published17 October 2014

- Published25 April 2014