What's behind Japan's snap election?

- Published

Japan's economy has slid back into a technical recession

Japan goes to the polls on 14 December for an election two years ahead of schedule. The BBC explains why Prime Minister Shinzo Abe moved the vote forward - and what he hopes to gain.

What was the trigger?

Mr Abe wants to ensure he has public support to push through his plans to revive the economy.

On 17 November, official numbers showed that Japan's economic output had shrunk for the second quarter in a row - which means the nation is now in what is called a technical recession.

The numbers also showed that growth in private consumption, which accounts for about 60% of Japan's economic health, was much weaker than expected.

Many analysts say that an increase in the country's sales tax in April which was intended to boost the national coffers has instead put consumers off buying new things, especially big ticket items like cars.

The increase in April was from 5% to 8% and there are currently plans to raise it again next year to 10%. Mr Abe wants to delay this, and sees an election win as giving him a mandate to do so.

"Ordinary people in Japan have stopped spending money," reports Tokyo Correspondent Rupert Wingfield-Hayes

Does this mean 'Abenomics' failed?

Mr Abe came to power in 2012 with a plan for economic reform. Launched the following year, the plan - which became known as Abenomics - was designed to help pull Japan out of two decades of deflation and kick-start its stagnant economy.

The plan was made up of three so-called arrows: monetary policy; fiscal stimulus; and structural reforms.

At first, the plan appeared to be working. Japan's central bank helped pump billions of dollars into the economy via its big stimulus package, and was confident enough to set a new inflation target of 2%.

The value of the yen weakened, which is a good thing for the nation's big exporters because it helps make Japanese goods cheaper to buy. And investors have been encouraged to buy shares in Japanese-listed firms, which has seen the stock market soar.

But the introduction of the sales tax, aimed at curbing Japan's crippling public debt, on the back of these improvements dented consumer confidence, which is vital to Japan's economic survival and ongoing growth.

Mr Abe wants to continue his economic reforms, however, and is seeking a fresh mandate from voters to do so.

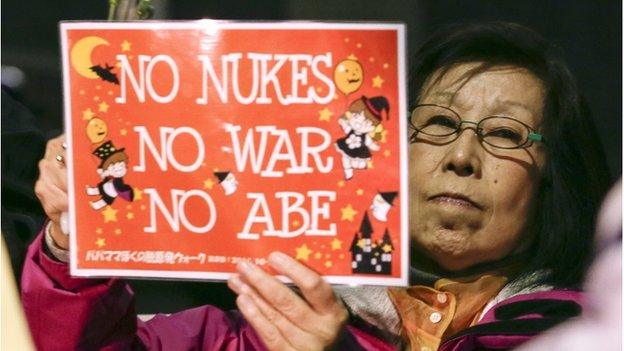

Nuclear energy and collective self defensive are unpopular policies that Mr Abe supports

So is it all about the economy?

Not entirely. If Mr Abe's plan works and he is able to solidify his majority in the lower house - as the latest polls suggest - he could gain a broader mandate to push through a number of publicly unpopular moves.

His cabinet has agreed a reinterpretation of Japan's post-war pacifist constitution to allow for the use of force to defend allies under attack, known as collective self-defence. Related legislation now needs to be passed by parliament.

Mr Abe also supports a return to the use of nuclear power to generate electricity to cut down on Japan's expensive energy imports.

After the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, public opinion has turned against nuclear power and all of Japan's reactors are currently inactive.

Shinzo Abe's party looks set for an emphatic win, polls suggest

Will it be a battle?

Mr Abe's Liberal Democratic Party looks likely to sweep the polls, as the main opposition remains in disarray after its election defeat two years ago.

Polls suggest Mr Abe could even expand the ruling coalition's majority in the lower house, winning seats formerly held by now-defunct minor parties.

The Banri Kaieda-led opposition Democratic Party is also expected to pick up a handful of seats, but not enough to affect the parliamentary balance.

Most commentators suggest that a strong Abe win would be more representative of a trust deficit in the opposition than a wave of support for the prime minister.