Closure from 1971 Bangladesh war comes at a high cost

- Published

Many people celebrated the execution of Mohammad Kamaruzzaman, but there have also been protests against the war crimes trials

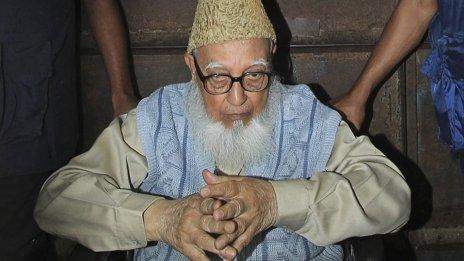

Last Saturday, Bangladesh executed a senior Islamist party leader, Mohammad Kamaruzzaman, for war crimes committed during the country's 1971 war of independence from Pakistan.

It was the second such hanging, with several more death sentences handed down by a domestic court set up to try local collaborators of the Pakistani army from that period.

The judicial process has come under repeated international criticism for not being up to standard, while supporters of the largest Islamist political party, Jamaat-e-Islami, have violently protested against the verdicts. But the trials have wide popular support.

As the BBC's Bangladesh Correspondent, I covered the first execution and some of the first verdicts.

Going through my notes, this stuck with me: closure is coming at a high cost.

Heroes need villains. Facts need counterfactuals. But what happens to those who lose the argument? Where do those who lose the war go?

Battles end, eventually. Then life resumes. The red lines drawn between them, and us, have to be smudged, if not washed off. But some lines, soaked with blood, divide people within nations and between tribes.

The closure craved after friends have tortured friends, brothers have killed brothers, neighbours have raped neighbours can be hard to find.

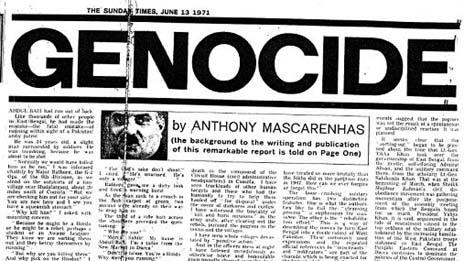

Four decades after the genocide in Bangladesh by the Pakistani army and their local militia, the urge for justice has cracked open old wounds. They had never healed, and their inherent maladies stem from a deeper crisis of identity: Bengali, or Muslim? If both, which comes first?

Recent violence

Let's go back to 2013 first. Quite often for hours, as I stood sandwiched between police officers, sometimes reluctantly leaning on the chalky whitewashed wall, verdicts were read out in the packed air-conditioned Dhaka courtroom of the self-styled International Crimes Tribunal.

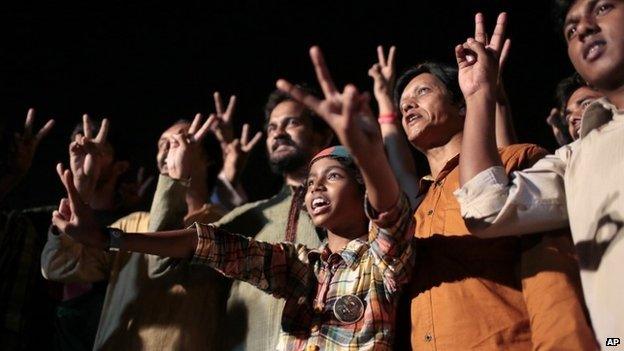

Bangladesh saw much violence in 2013 when the first execution for war crimes was announced

It would all turn a little rowdy after the first death by hanging was announced - the first count that is. Usually several death sentences followed. No-one paid much attention though at that point.

This court was trying Razakars, or collaborators, for their war crimes in 1971. It was to be the most violent year in Bangladesh's young life as hundreds were dying in clashes, external between police and the supporters of Jamaat. Most of those in the dock were from the party.

Forty-four years ago, Jamaat had officially opposed the breaking up of Pakistan. Many of its leaders and members led local militias active in the brutal campaign of killing and rape against their own people. But they could not stop Bangladesh's "bloody birth".

Bangladesh independence war, 1971

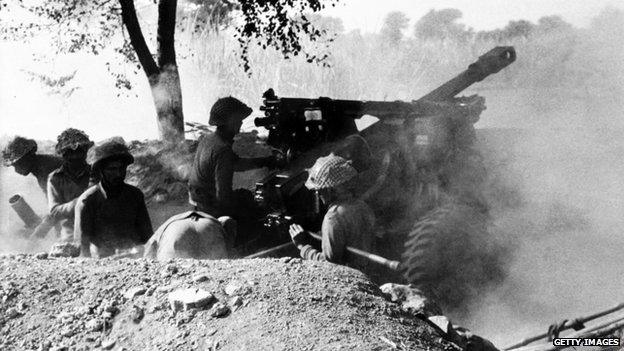

Civil war erupts in Pakistan, pitting the West Pakistan army against East Pakistanis demanding autonomy and later independence

Fighting forces an estimated 10 million East Pakistani civilians to flee to India

In December, India invades East Pakistan in support of the East Pakistani people

Pakistani army surrenders at Dhaka and its army of more than 90,000 become Indian prisoners of war

East Pakistan becomes the independent country of Bangladesh on 16 December 1971

Exact number of people killed is unclear - Bangladesh says it is three million but independent researchers say it is up to 500,000 fatalities

In the new nation's early turbulent years, the desire to move on led to an almost collective amnesia. Governments dodged the messy process of trying war criminals when those accused were living among them.

Successive military rulers seeking any sliver of legitimacy gradually rehabilitated Islamists accused of war crimes politically and economically - to take advantage of their minor yet crucial soft vote bank.

Political opportunism?

After years of pressure from a dedicated group of campaigners, when the current government of Awami League, the party which led Bangladesh into independence, finally started the war crimes trials in 2010 one could not ignore a whiff of political opportunism.

By now many of those suspected Islamists had become a mainstay of the opposition bloc. Some had even been government ministers in the past. Initial optimism gave way to criticisms from Western governments and international human rights groups surrounding the robustness of the judicial process, as it was a domestic set-up.

Then two years ago, a group of secular bloggers gathered at the capital's Shahbag roundabout demanding the execution of one of the convicted Islamists, after the court handed down a life sentence.

It captured the imagination of thousands of urban, middle-class young men and women, all chanting, "Hang the Razakars".

As their threat to the Islamists was carried live on television - the line between secular, liberal values and mob justice was blurred by pent-up nationalism.

While they did get what they wanted - a sentence of death, from an appeals court - it was soon to be a case of unintended consequences.

Slow descent

Bangladesh Awami League supporters protest with anti-Pakistan placards in Dhaka in December 2013

In moderate Muslim-majority Bangladesh, decades of stealthy Saudi Salafist funding for madrassas and Islamic charities has created an underclass of poor, working-class young men shifting to a more puritan and confrontational strain of the religion.

Now, feeling threatened from all sides, the Islamists came out of the woodwork. One afternoon that May, hundreds and thousands of madrassa students in traditional Islamic garb and skullcaps gathered at a different Dhaka roundabout - now showing their real numbers. Their favourite war cry, "Hang atheist bloggers". A new battle line was drawn.

Standing at the gates of Dhaka Central Jail well past midnight on the comfortable chill of that December, waiting with other reporters for the body of the first person to have been executed for war crimes to be carried out in an ambulance, I kept wondering what next. Not much, it appeared - that night, or the weeks that followed.

Then it started - the slow descent. Back in London, as I was the reading the news of another Islamist getting hanged this week, I read the last article on the Bangladesh timeline, barely two weeks old: secular blogger hacked to death in broad daylight by Islamists.

Remember red lines? Well, this one just turned deep red, again.

- Published10 March

- Published11 April 2015

- Published21 January 2013

- Published16 December 2011

- Published4 September 2016