Is it safe for Sherpas to go back to Everest?

- Published

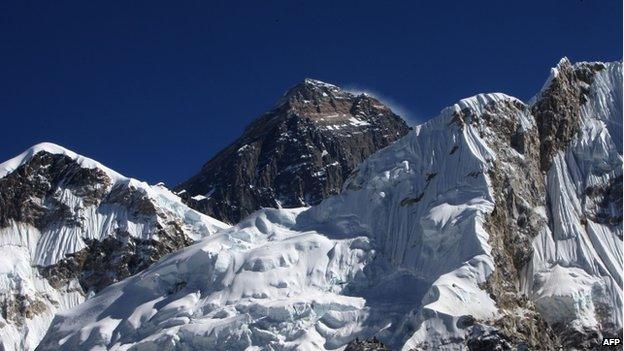

This week, mountaineers from across the world are inching their way over moving blocks of ice and craggy rock faces on their way to the summit of the world's tallest mountain.

In the short window of good weather that blows across the Himalayas before the summer monsoon, several hundred climbers are hoping to make it to the top.

But, not far from everyone's mind, will be the tragedy that struck the start of Everest summit season last year.

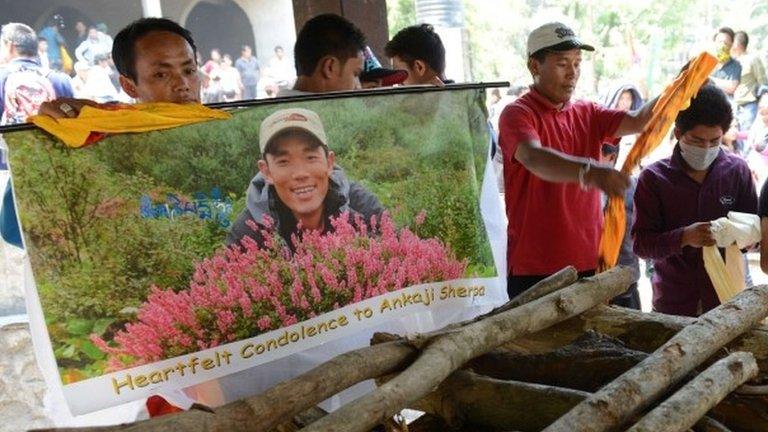

On 18 April 2014, falling blocks of ice killed 16 Sherpas as they attempted to fix guide-ropes through the glacial Khumbu Icefall at the base of the peak.

The accident led to angry protests by the mountain guides who demanded more compensation and higher insurance payouts from the government.

It also highlighted a recent increase in tension between Sherpas and Western climbers, which boiled over into a heated confrontation in 2013.

After the avalanche, the Sherpas cancelled summit season in honour of their dead comrades and hundreds of disappointed mountaineers were forced to return home.

A year on, much of this anger appears to have dissipated and the Sherpas are returning to work.

Sherpa guides say that their demands are still overlooked

New route

"Almost two-thirds of our demands have been fulfilled," says 39-year-old Pasang Sherpa, who scaled Everest seven times. "The rest are under implementation."

The government has increased the amount of insurance coverage for high-altitude workers by 50% to $15,000 (£10,000) and raised medical insurance by a third - with these increased costs paid for by expedition companies.

It has also provided more medical staff and helicopter rescue cover.

Nepalese people light candles in memory of the 16 Nepalese Sherpa guides killed in April 2014

Most importantly it has moved the route, external through the treacherous Khumbu Icefall away from overhanging ice-blocks that could break free and fall on climbers. The route is now further to the right - a path that is considered harder but less avalanche-prone.

This is important to the Sherpas who make the journey many times to bring supplies up and down the mountain, though experts say it's impossible to know whether the route is actually safer.

Securing a future

Representatives of the Sherpa community say they are satisfied for the moment, but would still like to see more done.

Mountain guides want better provision made for their families

"The government also needs to make arrangements to provide education for the children of mountain guides," says 32-year-old Phura Geljen Sherpa, who was involved in the rescue effort after the avalanche last year.

"And if good climbers are provided with pensions on their retirement, then their future will be secure," he says.

But the government say they are doing as much as they can.

"We have to look at our ground reality," says Tulasi Gautam, director-general of the Department of Tourism.

"If we continue to increase the facilities, the cost of climbing goes up. Foreign climbers then may opt to climb from the Chinese side or go to other countries for mountain climbing."

Frustrations

It's not just the Sherpas who would like to see the government invest more in the Everest industry.

"There has never been a formal inquiry into the avalanche," says Simon Lowe, managing director of the British mountaineering company Jagged Globe.

"We need to try to work out what factors led to the tragedy. But no-one took statements. It's one of the frustrations of dealing with Nepal."

Everest summit season is upon us once again

Lowe has issued his Sherpas with avalanche transceivers that transmit a continual beep to help search teams locate them if they become buried.

But without an inquiry into last year's accident, he says he doesn't know how useful they are.

"We don't know whether the Sherpas died from trauma from being hit by falling ice, or whether they were buried. If they were buried these will help get them out," he says.

Mount Everest

Peak is 8,848 metres (29,029 ft) above sea level

First successful ascent was by New Zealand mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay on 29 May 1953

More than 4,000 people have scaled the summit since then

Hundreds of people attempt to climb Everest every year - 658 people made the summit in 2013

More than 200 people have died trying to climb Everest

Mountain reform

Lowe would also like to see the government change its business model.

At the moment Nepal charges $11,000 for a group permit to climb Everest, an increase of $1,000 from last year.

It would be better, says Lowe, if the government forced Everest hopefuls to scale lesser Nepal-based peaks first, and to charge them more for doing this. He believes this could generate increased income as well as solve the problems of overcrowding and inexperienced climbers on Everest's slopes.

It's clear that the changes brought in this year are just the start of much-wanted reform of the Everest-climbing industry.

But, despite the continuing issues and danger, the allure of conquering the tallest peak on earth has not diminished.

"Disasters happen," says Pasang Sherpa.

"I was once swept away by an avalanche and was unconscious for almost an hour. But I came out of it and have still not lost my interest in climbing."

- Published22 April 2014

- Published21 April 2014

- Published18 April 2014