What is behind Pakistan's dramatic rise in executions?

- Published

The faces of some of those awaiting execution and others who have already been put to death

In December 2014 Pakistan lifted a seven-year moratorium on executions in response to a deadly Taliban attack on a school in Peshawar. Since then more than 300 people have been put to death, according to Amnesty International and the Justice Project Pakistan. The vast majority were not convicted of terror offences.

What explains Pakistan's dramatic shift in death penalty policy?

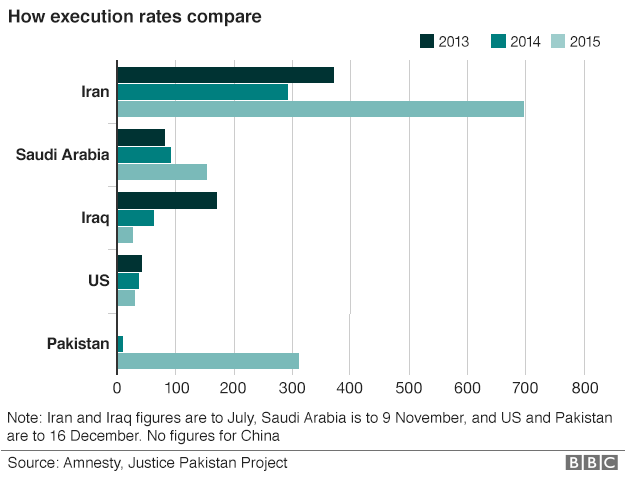

How does Pakistan compare with the rest of the world?

The issue of capital punishment sparks heated debates around the world. Although 99 nations have abolished the death penalty, 22 countries carried out executions in 2014.

China and North Korea are believed to be among the world's top executioners. However, specific figures are difficult to obtain because they are concealed by the authorities.

Amnesty International does collate figures from other countries, external, which show Iran and Saudi Arabia have carried out many of the world's executions in recent years.

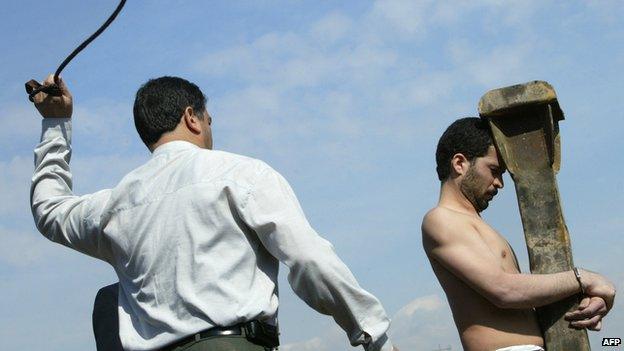

Convicts are often flogged before execution in Iran

Iran had carried out at least 694 executions as of July 2015, Amnesty told the BBC, many more than the figure acknowledged by the authorities.

As of 9 November Saudi Arabia had executed 151 people in 2015, Amnesty said. That compares with 90 in the whole of 2014.

Pakistan has quickly caught up - it had executed 316 people by 16 December, the anniversary of the Peshawar massacre.

Who is on death row in Pakistan?

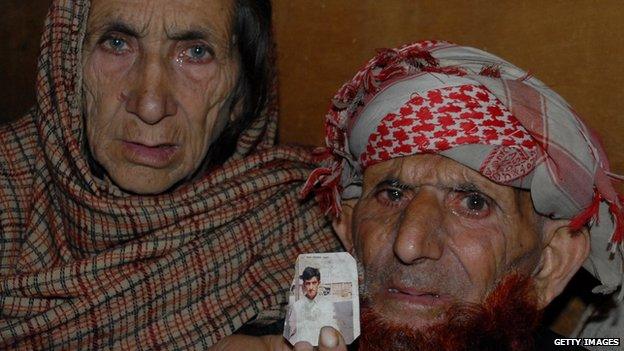

Shafqat Hussain's parents did not see their son for more than a decade

Pakistan is believed to have the largest number of death row inmates in the world. The government said in October that 6,016 prisoners were awaiting execution - other estimates have put the figure at about 8,000.

Many death row inmates have been in jail for more than a decade. Almost all are men, however there are some women - most notably the Christian Asia Bibi who was convicted of blasphemy in 2010.

The mother-of-five was accused of insulting the Prophet Mohammed and sentenced to death, despite her insistence that the evidence against her had been fabricated.

Some 27 crimes, external carry the death sentence in Pakistan, including terrorism, rape and adultery. Figures from the Justice Project Pakistan, external show most people facing execution have been convicted of a "lethal offence".

However, in Pakistan's most populous province Punjab, for example, 226 prisoners were on death row for "non-lethal offences", the JPP told the BBC earlier this year.

The latest case to attract global attention is that of Abdul Basit, a paraplegic who is on death row for murder. His execution has already been delayed twice over concerns that hanging him would be degrading and in breach of Pakistan's jail manual which does not set out how to put someone in a wheelchair to death.

Basit has been paralysed since 2010 - jail rules do not allow for hanging people in wheelchairs

There are also concerns that up to 1,000 people convicted as juveniles are facing execution - something that is illegal under international law. But proving your age in Pakistan can be difficult, particularly in poor communities where many births are not registered.

In June Aftab Bahadur was put to death, even though human rights campaigners said there was evidence which proved he was a minor when he was convicted of murder in 1992. They also said he had been tortured into giving a confession.

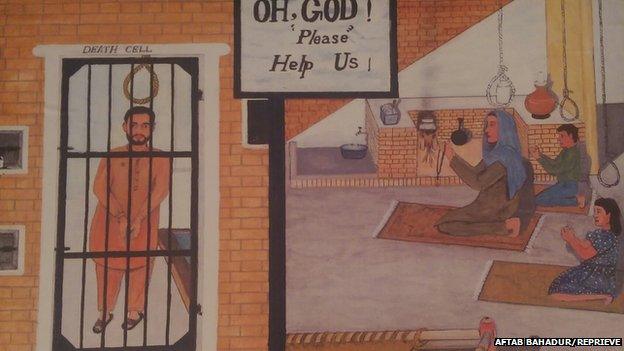

Aftab Bahadur had been on death row for 23 years

Aftab Bahadur painted about his situation whilst in prison

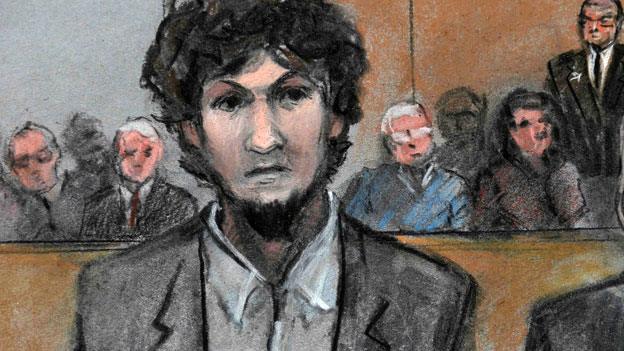

And on 4 August Shafqat Hussain was executed, despite appeals from campaigners who said he was a minor when convicted. His execution was postponed four times before he was hanged.

He was found guilty of killing and kidnapping a seven-year-old boy in 2004 - but his lawyers also maintained he was underage when the boy was killed.

Why was the moratorium lifted?

The bloody scenes in Peshawar sparked calls for the government to do more to target terrorists

The massacre of 132 children in Peshawar last December was the catalyst for the reintroduction of the death penalty.

Amid public anger, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif announced the moratorium would be lifted for terror convicts - before eventually resuming executions for all death penalty offences. No specific reason was given for the second decision.

The move was condemned by the United Nations and human rights campaigners who warned it would do little to impede the Taliban.

"The government is touting executions as the way of tackling the country's law and order problems," said Maya Pastakia, a Pakistan campaigner for Amnesty International.

"But there is no compelling evidence that the death penalty will act as a particular deterrent over and above any other form of punishment. A suicide bomber won't be deterred by the death penalty."

She believes lifting the moratorium was "a lazy response" to dealing with the huge numbers of people on death row.

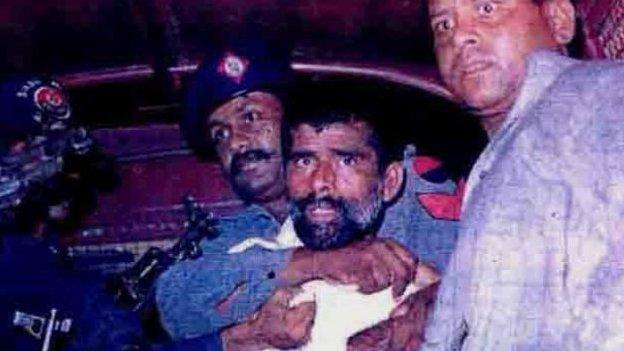

Saulat Mirza (seen in the photo) was executed in May over a political killing

"We have seen a conveyor belt of executions. People who were implicated in terrorism crime, as well as people convicted for straight-forward murder, manslaughter and kidnapping.

"The government seems entirely intransigent on this issue."

Who has been executed and why?

Two Baloch hijackers were executed for storming a Pakistan International flight

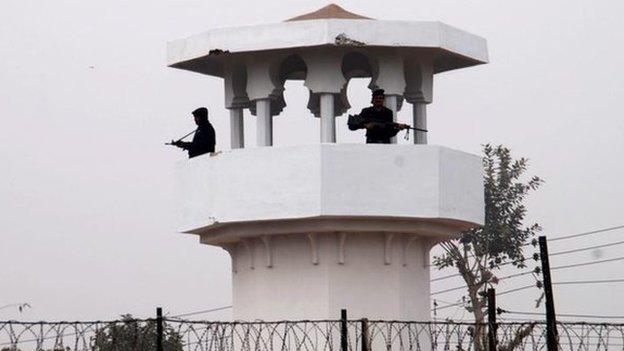

The first series of hangings took place at Faisalabad jail in December - and are now almost an everyday occurrence across the country.

Many prisoners have been put to death for terror offences, including three Baloch insurgents who hijacked a passenger plane in 1998.

Others were found guilty of political killings, like Saulat Mirza - a former worker for the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) - who was convicted of murdering the head of Karachi's power utility service.

But some cases have attracted attention over concerns about the legitimacy of their trials.

Shafqat Hussain "was at worst a common criminal", according to his lawyer Sarah Belal, yet his case was processed by an anti-terrorism court.

"It goes to the heart of all the problems with the judicial system," she told the BBC. "He belongs to a poor community. He was not a terrorist."

Saulat Mirza's family grieve over his coffin following his execution in Balochistan province

Ms Belal says Shafqat Hussain was tortured for nine days before giving a confession, which he later withdrew. All other evidence against him was "purely circumstantial".

She says there has never been a credible investigation into his age or the validity of his torture claims.

BBC correspondents say the authorities did allow for last-minute investigations into his age but in the end said there was no evidence that he had been a minor at the time of his conviction and his appeals for mercy were turned down.

Shafqat Hussain claims he was electrocuted and had his fingernails pulled out

Cases like this are not uncommon, according to Maya Pastakia.

"Trials are often characterised by lack of access to fair legal counsel," said Ms Pastakia. "Often the accused in the initial stages will be given a state appointed lawyer who is often poorly trained and lacks competence.

"All judicial systems make mistakes and as long as the death penalty persists, innocent people will be executed. There is no going back."

Interviews and additional research by Claire Brennan

- Published23 May 2015

- Published4 August 2011

- Published4 February 2015

- Published10 March 2015