How dawn rain delayed execution of Pakistani Abdul Basit

- Published

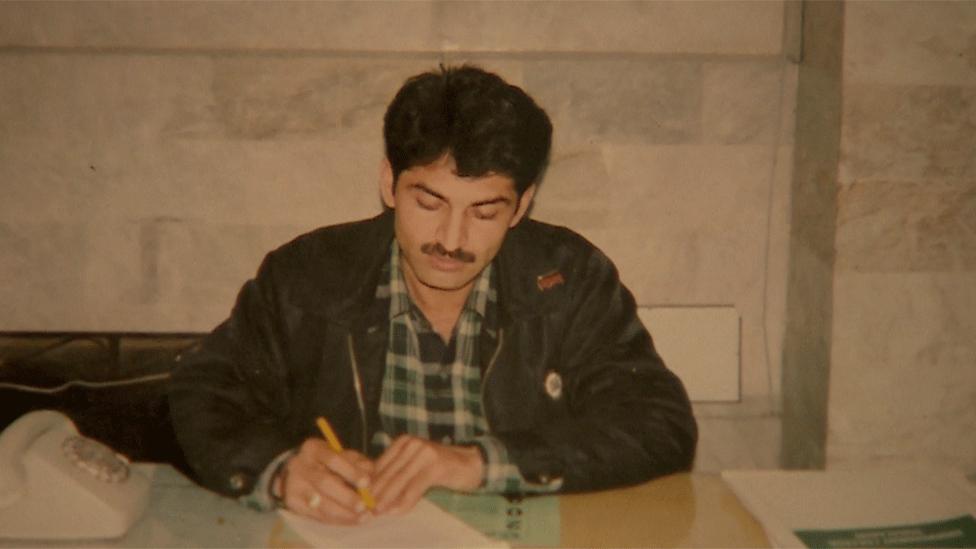

Abdul Basit's problems began after he married and then fell in love with another woman

On death row for murder, Pakistani paraplegic Abdul Basit was minutes from being hanged before a last-minute delay saved his life in September. His family fear a rescheduled execution could take place later this week.

Campaigners say hanging him would be degrading and in breach of Pakistan's laws. M Ilyas Khan in Lahore pieces together his story.

Lying in his cell attached to a catheter that September evening, Abdul Basit said his final farewells to his wife and mother, and handed his will to a jail official.

Before dawn the next day, on 22 September, he was helped into the mandatory black pyjama-suit and taken in a wheelchair towards the gallows.

But half way there, a prison guard came rushing to say jail bosses wanted them to wait until the rain stopped.

So they waited under a metal shed. The rain rattled on the roof, then turned to drizzle, then stopped, then started again. This pattern repeated several times, but there were no orders for them to proceed.

Finally, word came that the hanging had been postponed.

For nearly two hours Basit waited to meet his death - sitting in his wheelchair, his arms and wrists tied behind the chair's back.

What went on in his mind during that time?

Zainab Mahboob, a lawyer working with Justice Project Pakistan (JPP) which is pursuing Basit's case, says he is not the kind of man to talk about his emotions.

"I guess he [is] a bit uncomfortable opening up about his past… about what happened."

Shooting

Abdul Basit has had plenty on his mind.

Basit married Musarrat Nosheen - but then fell in love with another woman

The son of a mid-level police officer, he had to quit college to support his family after his father died. In 2003, when he was managing a medical college in his native Faisalabad city, he fell in love with an English Literature student Musarrat Nosheen. They were married that year.

The family is tight-lipped about their past, but there were disagreements and Basit moved into a separate house with his wife. Their problems worsened in late 2007 when he fell in love with another woman, a student of the medical college he worked for, and decided to marry her.

The woman, Sadaf Shehzad, came from a family of lawyers from Okara, a city 100km (62 miles) south of Faisalabad. Incensed, Nosheen left Basit - and her two sons - and went to live with her mother.

When Sadaf's family found out about the affair, her uncle, a student of law, rang up Basit and exchanged harsh words with him, Nosheen says.

Tension was so high that when one of their sons briefly went missing, a panic-stricken Basit reported to police that he had been kidnapped by Sadaf's uncle, Nosheen says. The child was found the next day.

Basit has been paralysed since 2010 - jail rules do not allow for hanging people in wheelchairs

Read more:

What is behind Pakistan's dramatic rise in executions?

The Pakistani hangman and his family tradition

Subsequently, Sadaf's family did however agree to the marriage - provided Nosheen gave consent. She says she decided to forgive him "in the best interest of my children", and accompanied him to Sadaf's house in Okara to settle the matter.

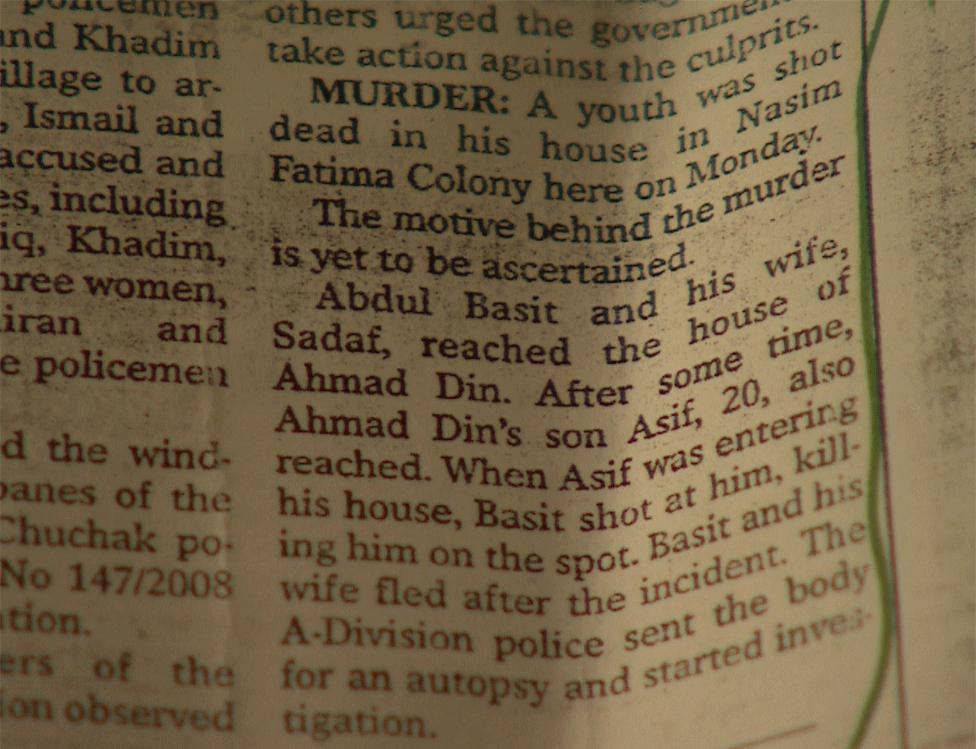

That is where she says Sadaf's uncle, driven by family honour, attacked Basit, and Basit, who always carried a gun "for personal safety", shot him. He died on the spot.

Sadaf's family have a different account, case records show.

They say Basit asked Sadaf for bribes to get her a document she needed for college admission, which led to the altercation between him and Sadaf's uncle - when the kidnapping accusation was later found to be "false", Basit drove to Okara with two male accomplices to kill him.

They say family members caught Basit, but the other two escaped. They were never arrested or heard from again.

Jail riots

The court ruled that eyewitness and medical evidence supported the version of Sadaf's family and proved that it was a premeditated murder - hence the maximum penalty of death.

A Dawn newspaper cutting reports the Okara murder

Nosheen's testimony could have established the murder as the result of "sudden provocation", entailing a lesser sentence, but she was seen as an unreliable witness due to a legal technicality.

Her relatives, in keeping with conservative middle-class values that discourage exposing women to police and criminal proceedings, got her released from police custody allegedly by paying bribes. And so the police record does not show her as having been arrested along with Basit, or having been present there.

Whatever the omissions and commissions of the trial, if Basit had been able to stand unaided, he would have been dead by now.

He survived because he was caught up in jail riots that broke out during the last week of January 2010.

As the prisoners and jail guards fought battles for over a week, Basit contracted tubercular meningitis and lay in his cell without being noticed.

He was left paralysed from the waist down.

Pakistani prison rules provide for specific measures of the length of the noose and the drop to ensure instant death without decapitation or strangulation. They presuppose that the convict can stand on their feet on the gallows.

On 21 September, days after his death warrant was issued, the JPP lawyers' petition for a reprieve on grounds of him being medically unfit for hanging was dismissed by the Supreme Court. But there was a hope-inspiring line in the court order which directed jail officials to "comply with the relevant rules".

That evening, the JPP team drove to Faisalabad to discuss the rules with the prison authorities, says Zainab Mahboob.

Regardless of what impact their discussions might have had, an air of confusion already prevailed among prison officials that night.

'Closer to God'

Basit told Zainab days later that the prison guards showed no urgency preparing him for the gallows.

Lawyer Zainab Mahboob says the JPP spent hours locked in discussions with the jail authorities

"He had been up since before the break of dawn, praying, but he hadn't been given the hanging clothes until nearly 5:30, so he himself asked for the clothes because it was getting late."

They had designed a tall wooden stool to support him in a semi-standing position, which was to fall with him during the drop, but then they decided that it wouldn't work, said a prison guard, quoting one of his colleagues who was on duty with Basit that morning.

He said that during the two hour-wait under the shed, he asked the officials a couple of times why they couldn't just get it over with as the rain had stopped,

A week later, when his wife and mother visited him in jail, he showed them the marks that the rope they tied him with had left on his arms and wrists.

His wife is hopeful that after having helped Basit escape the gallows, God may have a "long-term plan for him".

"He wasn't like this before. He was a worldly, materialistic person, but now he has moved closer to God."

And he has admitted to Nosheen that he has not been fair to her.

"He may have to spend the rest of his life as a paralysed person, but he can see, he can think, and so he can intervene, he can support… he can be a father to his children."

But the clock is ticking faster than ever.

The jail magistrate only "temporarily" postponed his execution, pending one of two developments; an amendment in jail rules, which could pave the way for his execution, or a presidential pardon.