Myanmar elite 'profits from $31bn jade trade'

- Published

As Jonah Fisher reports, control of much of Myanmar's lucrative jade market is still in the hands of the former military junta

Jade mining companies connected to the army in Myanmar may have carried out "the biggest natural resources heist in modern history", say transparency campaigners Global Witness.

Their report, external claims jade valued at a staggering almost $31bn (£20bn) was extracted from Burmese mines last year.

It estimates that the figure for the last decade could be more than $120bn.

Presented with the data by the BBC, the government did not question the quantity or valuation of the jade.

But it said most of the gemstones from the last year had been stockpiled, with only a small fraction sold so far.

'Extraordinary sums of money'

To operate a mine in Hpakant you need military connections

Hpakant, in Kachin state, is the site of the world's biggest jade mine. We were stopped from travelling there by the chief minister, but footage obtained from the site shows huge articulated vehicles turning mountains into moonscapes.

With an election on the horizon and considerable political uncertainty the companies involved are clearly in a hurry.

To operate a mine in Hpakant you need military connections. The main companies listed in the Global Witness report are either directly owned by the army, or operated by those with close ties.

A few are run by those connected to ethnic armies, in return for them maintaining a ceasefire.

"If a military family does not have a jade company they are something of a black sheep," Mike Davis from Global Witness said. "These families are making extraordinary sums of money, often in the tens and hundreds of millions of dollars."

Retired general Than Shwe's family allegedly made more than $220m in jade sales in 2013 and 2014

Prominent among those allegedly profiting from the trade are jade companies owned by the family of retired senior general Than Shwe. As the military ruler of Myanmar, also known as Burma, between 1992 and 2011, he presided over a period in which demonstrations were brutally repressed and opponents imprisoned. Despite having retired many still think he's influential behind the scenes.

The Global Witness report - Jade: Myanmar's 'Big State Secret' - claims that companies connected to Than Shwe's family made more than $220m in jade sales in 2013 and 2014.

Several of the other companies are linked to recent ministers but most named were at their most prominent before Thein Sein's quasi-civilian government came to power in 2011. None were immediately available for comment.

Crunching the numbers

Global Witness says the likely total value of jade production in 2014 came to close to $30bn

More than a year in the making, this report digs deep into previously unseen Burmese government figures.

To reach the headline number of nearly $31bn extracted in 2014 they took the officially recorded figure for jade production (16,684 tonnes) and then estimated, based on previous studies, the proportion that's likely to have been mined of each quality or "grade".

Using the prices for each grade from publically recorded sales they then calculated the likely total value of jade production. That came to a jaw-dropping $30.859bn.

To double-check this number, Global Witness then obtained customs data for jade imports into China. Last year precious and semi-precious stone imports from Myanmar were valued at $12.3bn on a weight of 5,402 tonnes. The researchers' analysis of the data shows that almost all of that was jade.

Using the officially declared production figure for 2014, and keeping all things equal (to the average value of declared imports into China) then the estimated value for the jade mined in 2014 is $37.98bn.

Clearly in both methods estimates are being used, but the ballpark figure remains similar and huge. The real total could even be much higher with many insiders saying that the best quality jade never goes through the books and is smuggled directly to Chinese buyers.

This contents of the report challenges the Burmese army narrative of recent history. The military has long said that it keeps a tight control of Burmese political life to maintain stability and, in the face of numerous ethnic wars, to prevent the country disintegrating.

It was, the people were told, a selfless act to maintain the unity of a troubled country.

This report makes it clearer than ever before that the top brass used their privileged positions to award themselves choice concessions and contracts and become extremely rich.

'A stage of democratic transition'

Ye Htay, a director from the Ministry of Mining, confirmed that the valuation of the jade mined in 2014 at $31bn was plausible, but said that most of it had been stockpiled and not sold.

Sales through the Nay Pyi Taw emporium last year were close to $1bn, he said, with about $90m paid in taxes.

He was much less forthcoming when pressed on how the concessions were awarded and the dominance of military companies.

He said Myanmar was "in a stage of democratic transition" and that such moves "haven't happened during the last five years".

There is an element of truth in that. The most egregious abuses do seem to date back to before 2010, and all agree that there have been moves towards greater transparency.

Jade is a key source of financing for both sides in Kachin State, says Mike Davis from Global Witness

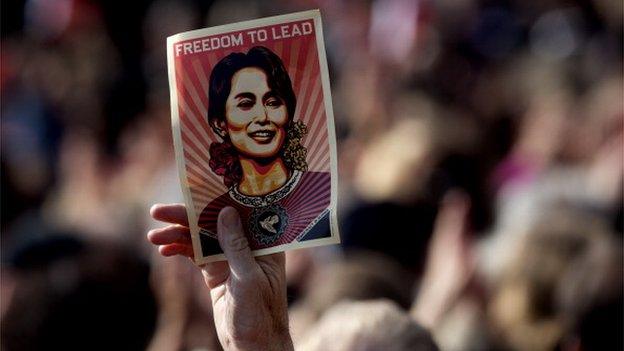

This report underscores just how difficult it will be to prise the Burmese army away from political power.

It also helps explain why the conflict in Kachin State, where the mines are, has proved so difficult to resolve.

Last week, rebels from the Kachin Independence Army refused to sign a nationwide agreement with the government - aimed at ending decades of civil conflict - and clashes with the Burmese army continue.

"Jade is a key source of financing for both sides," Mike Davis told me.

"There is an incentive there for the hardliners on the government side to keep the conflict going until such time as they can be confident that when the dust settles, their assets will still be there."

Most proposals for a lasting federal settlement to Myanmar's long running ethnic conflicts involve greater transparency and the sharing of wealth from natural resources in the states where they are extracted.

It's easy to see why peace and democratic transformation aren't attractive options for those making hundreds of millions from exploiting the jade mines.

- Published15 October 2015

- Published3 December 2015

- Published14 July 2014

- Published2 October 2015

- Published8 July 2015

- Published26 May 2023